Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Acknowledgments

From Alfredo

Thanks to Karin Yngvesdotter, Michele Wesen-Bryant, Howard Davis, Joseph Sullivan, and Evelyn Lontok-Capistrano for their help, guidance, advice, and support.

From Matt

Thanks to David Blaisdell, Sorche Fairbank, Taylor Forrest, Sarah Handler, Karyn Polewaczyk, Megan Ross, and Suzanne Spellen.

Other books in the 101 Things I Learned series

101 Things I Learned in Advertising School

101 Things I Learned in Architecture School (MIT Press)

101 Things I Learned in Business School, Second Edition

101 Things I Learned in Culinary School, Second Edition

101 Things I Learned in Engineering School

101 Things I Learned in Film School

101 Things I Learned in Law School

101 Things I Learned in Product Design School

101 Things I Learned in Urban Design School

Authors Note

A good fashion design curriculum encourages students to come up with informed, creative solutions to the problem of dressing people for their lives. In my years of teaching, I have found that the greatest obstacle to this goal is not the acquiring of technical proficiency or adequate intellectual informationwith the availability of information today, the average eight-year-old is likely more sophisticated and fashion-savvy than everbut with accepting the need to design for real people.

The perception on the part of many students (and sometimes instructors) is that realityreal customers with real needs, real fabrics that must be constructed into real garmentsis the enemy of creativity. Real experience, it is feared, means drudgery, compromise, and mediocrity. The result is that most curricula tend toward the theoretical, with practical application addressed only to the extent it is considered unavoidable. Students designs often seem to resemble ideas more than clothing.

It took me years as a working designer to accept the importance of identifying a real living customer and recognizing what he or she will and wont wear. Far from being anti-creative, this realization was for me the beginning of true creativity. For what is creativity if it isnt to take something existing in ones head and give it relevance in the real world?

The central purpose of this book, then, isnt to impart technical proficiency (although we hopefully will do some of that) or to challenge students creatively (though I hope to do that too), but to give readers some ways to connect the two. I hope to provide students with small reminders, touchstones, and catalysts to help them solve real problems creatively, and creative problems realistically.

I hope that students and designers will keep this little book handy while researching, designing, swatching, and illustrating. I hope the history lessons help readers understand that innovation happens in context and through reaction to what came before; that the lessons in organization motivate the development of a holistic design process; that the lessons in illustration demonstrate the importance of communication; and that the business lessons lend a sense of the designers role in the larger world.

Alfredo Cabrera

Alfredo Cabrera is an award-winning fashion designer and illustrator. His clients have included Henri Bendel, Tommy Hilfiger, Polo Jeans, Express, The Limited, Girbaud, Jones New York, Nautica, FUBU, Izod, and Liz Claiborne. He is based in New York City, where he is a faculty member at the renowned Parsons Institute/New School for Design.

Matthew Frederick is a bestselling author, instructor of design and writing, and the creator of the 101 Things I Learned series. He lives in New Yorks Hudson Valley.

101ThingsILearned.com

Fashion was born in the 12th century.

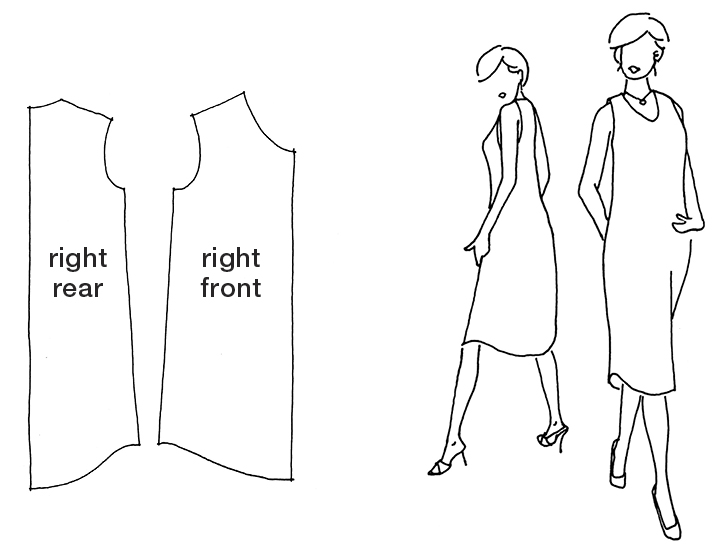

There are two ways to clothe the human form. In draping, simple pieces of cloth are wrapped around the body, with the excess falling in natural folds. This was the earliest method of making clothing from textiles. Tailoring dates to the Early European Renaissance of the 12th century, when a celebration of the natural world in science, philosophy, and art also brought about a focus on the human form. The draped robe was divided into multiple pieces that more closely fit the body. Over time, these pieces led to the making of patterns templates for creating multiple, consistent garments. The advent of tailoring was thus the birth of fashion.

Draped garments are common today, but they almost always have a tailored understructure. Traditional draped clothing was ephemeralit lost its shape when not in contact with the body.

Pattern for a sleeveless dress

Fashion-ese

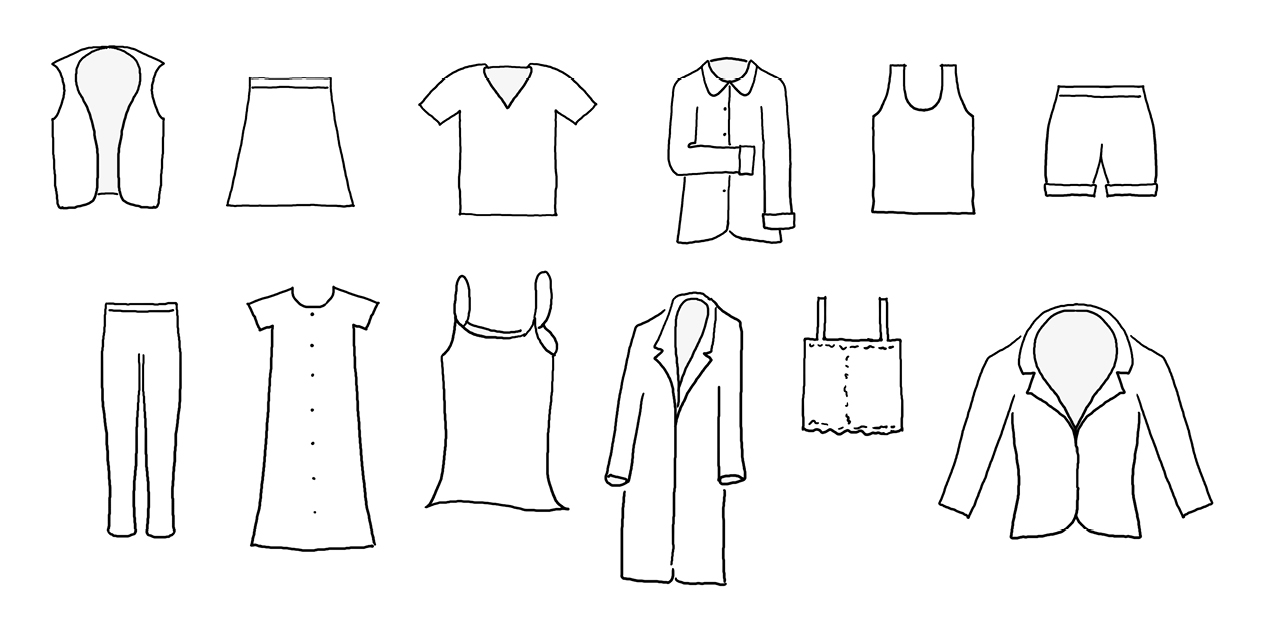

collection: n. 1. a thematically cohesive group of garments created by a designer for a season. 2. a category of clothing, e.g., an outerwear or swimwear collection.

drape: 1. n. the reaction of a fabric to gravity, how it falls. 2. v. to manipulate a fabric on a dress form while creating a design.

fabric story: n. a group of fabric samples conveying a designers selections for a collection. Sometimes referred to as a fabric storyboard or a fabrication.

finish: n. 1. the surface texture of a woven fabric. 2. a final fashion drawing.

fit: 1. n. the way a garment drapes or falls on the body. 2. v. to make adjustments to a muslin or garment sample on a model or mannequin.

line: n. 1. the general silhouette or flow of a garment, e.g., the line of an evening gown. 2. a synonym for collection, e.g., our fall line emphasizes a retro look.

muslin: n. 1. an inexpensive, finely woven cotton fabric. 2. a prototype garment, created to refine design and fit; called a muslin regardless of the fabric.

pattern: n. 1. a template for the individual pieces of a garment, from which multiple examples of the garment are made. 2. a visual design, e.g., a check, stripe, or floral pattern.

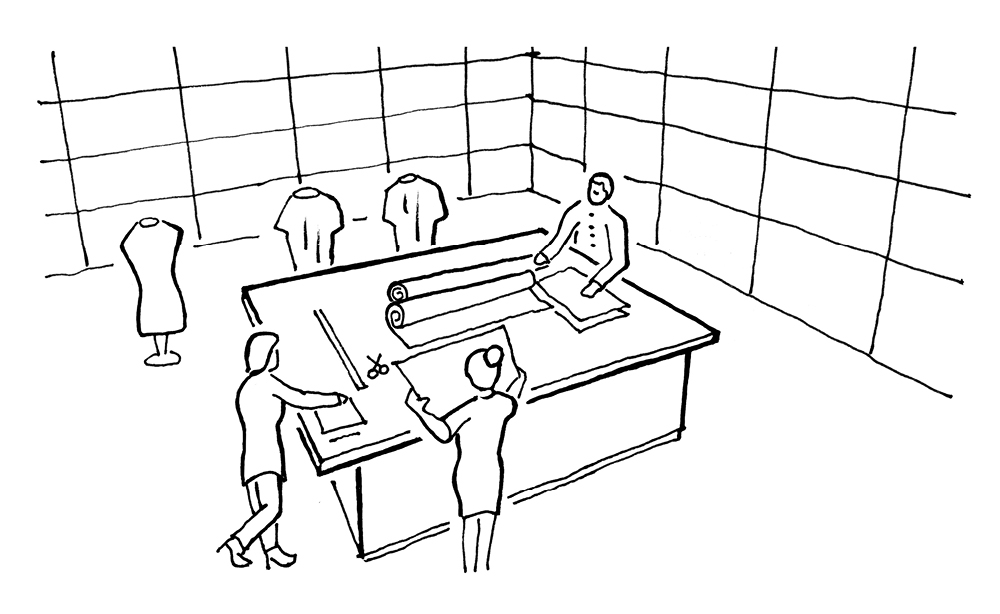

Who does what

fashion designer: conceives, designs, and directs the creation of a fashion collection or fashion category.

production manager: creates costing and logistical plans for a fashion house or design firm.

patternmaker: determines the exact two-dimensional shapes of fabric needed to make a design realizable as a three-dimensional garment.

cutter: cuts fabric in the shapes determined by the patternmaker; works in a fashion house or factory.

sample-hand: constructs the first sample of a garment for the designer. Sample-hands include tailors, sewers, knitters, and embroiderers. Workers who fill two or more of these roles are called sample-makers.

machine operator: a factory sewer (although never a sample-hand); in a past era, seamstress referred to a female machine operator.

buyer: an employee of a retail store or chain who selects the apparel it will sell.

fashion editor: creates themes for photo shoots in the media and selects styles from various designers to illustrate those themes.

influencer: affects popular opinion, aesthetics, and purchasing patterns through social media. May or may not have a formal position in the fashion industry.