This book made available by the Internet Archive.

To ARTHUR

who makes my whole world smell sweet

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the many experts who gave of their time and knowledge, in particular: Lee Horn and Darrel Huebner of the 3M Company; Lynn Waplington and Jane Barr of Burson-Marsteller; Peter Midwood, Hugh Watkins and Juanita Byrne-Quinn of Proprietary Perfumes, Ltd.; Annette Green of the Fragrance Foundation; Ernest Shiftan of International Flavors and Fragrances; Richard P. Michael, Ph.D., of Emory University; Dr. Richard Doty and Dr. George Preti of the Monell Chemical Senses Center; Dr. Robert I. Henkin of Georgetown University; Dr. Andrew Dravnieks of the Illinois Institute of Technology; Dr. J. E. Amoore of the U.S. Department of Agricultures Western Regional Research Laboratory; and Dr. A. A. Schleppnik of Monsanto Flavor/Essence, Inc.

Part I:

Scent Language

1 Smell Signatures

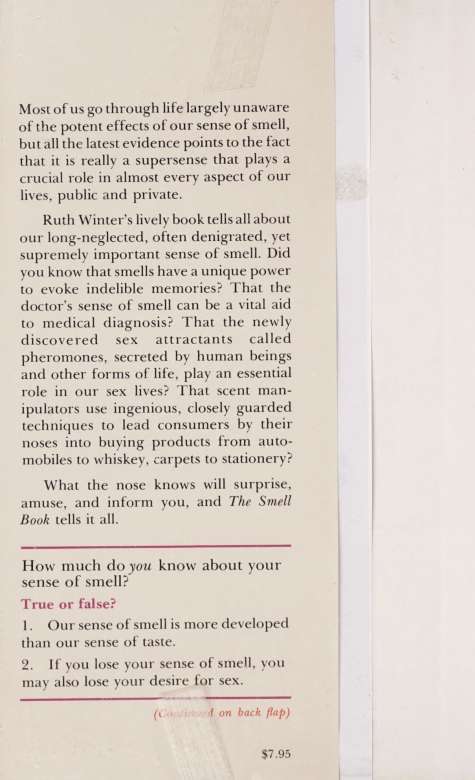

No matter how we scrub and clean ourselves, we all emit a unique individual odor. Furthermore, we are all profoundly affected by other peoples odors and by the odors in our environments. No aspect of our behavior is immune. We communicate with a silent, invisible, often subliminal smell language in our bedrooms, dining rooms, officeswherever we are.

Our ability to receive smell messages accompanies us into the world at birth. Before our other senses are fully operative, we are receiving survival information through our noses, which tell us where and who our mothers are and the location of the food they provide.

The sense of smell gives us sexual, gustatory, and psychological pleasure. It stimulates our memories and remains faithful to us long after the other senses have dimmed. Our olfactory sense functions when the other senses do not. We need light for sight and the direct application of molecules to the tongue for taste. When we sleep, our senses of hearing and touch are partly turned off but our noses are ever vigilant. And yet, we are not proud of our sense of smell. We brag about our twenty-twenty vision and our fine palates, although we

THE SMELL BOOK

can taste only four things and flavor is largely aroma. We tout our keen sense of hearing, but we do not boast about our ability to smell.

We dont even have an adequate vocabulary for our sense of smell. The word smell is confusing, as it serves as both a verb and a noun. And we have no names for specific odors; we say only that they smell like something or other.

Why are we so self-conscious about our ability to smell?

First of all, it reminds us that we are animals. Its true that we dont go around sniffing each other quite as obviously as dogs and rats, but you have only to watch a human mother sniffing the head of her infant to realize how instinctive smell behavior is; and you have only to consider how you react to the scent of someone you love to recognize how smells affect us socially.

In a fascinating experiment illustrating social smell behavior, researchers from the University of California tested scent and the use of personal space, using male and female stimulus persons at an amusement park. When the experiment participants wore perfume or aftershave lotion, the individuals standing in line close by them moved farther away than when no scents were used. The stimulus persons apparently were repellent to others in their environment despite the fact that the perfume and after-shave lotion they wore were popular, pleasant scents. Evidently, the desire to protect ones personal space from scent stimulation emanating from strangers is unconscious but irresistible. This behavior is amazingly similar to that of animals in the wild when a strange member of the species is introduced into their home territory.