This book made available by the Internet Archive.

the memory of RobertM. Crump and to RuthM. Crump, who shared their love of natural history with us

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014

https://archive.org/details/headlessmalesmakOOcrum

Preface

ZOOLOGISTS ARE a curious lot. They poke and probe animals to understand how they work. They enclose everything from ants to anteaters in chambers and measure water loss or respiratory rate. They count scales and teeth on preserved specimens in hopes of discovering new species. Some zoologists watch animals to describe their natural history: how they choose their mates, whether or not and what type of care they provide for their young, what food they eat and how they get it, how they defend themselves, and how they communicate. I'm one of the latter group.

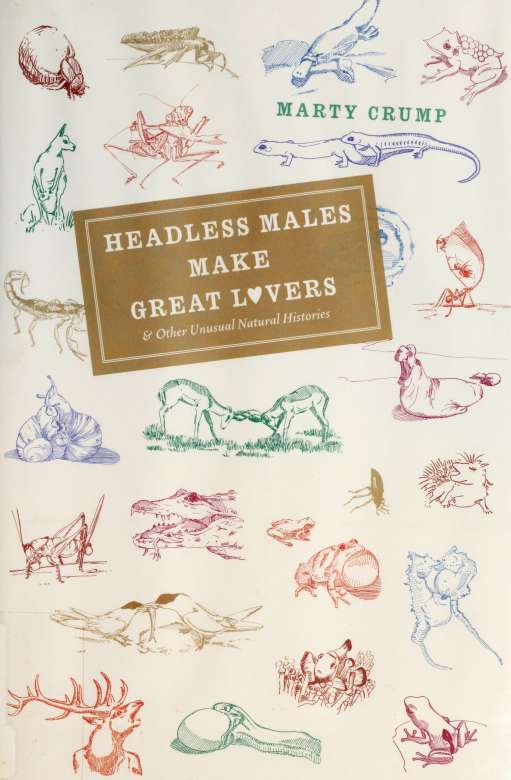

This book celebrates animal diversity. I've purposely focused on bizarre "gee whiz" stories. Some are based on my own research or that of friends and colleagues; others come from scientists whom I don't know personally. The animals run the gamut from sponges to mammals, and they include examples from all over the world. The animal natural histories I've selected are an eclectic assortment, grouped into five fundamental themes: mating games, parental care, food and feeding, defense, and communication. They are a tiny sampling of the fascinating animal behaviors that naturalists have described.

My goal in writing this book was to convert scientific observations, some of which lie buried in the technical literature, into a readable form for a general audience. If I can whet the appetite of a few budding naturalists and increase curious laymen's appreciation for natural history, then I will have been successful.

Scientists writing for a general audience sometimes straddle a fine line. We're either too technical, stilted, and dry, or in our enthusiasm to excite the reader, we come across as teleological (assuming animals behave with a conscious design or purpose in mind) or anthropomorphic (attributing human characteristics to animals). If in my effort to engage the reader I sometimes stray from the center line, please know that I do not suggest that animals behave with a conscious goal in mind or that they react to situations as a human would. I'm simply tripping over my own enthusiasm.

X I PREFACE

Although I've avoided scientific jargon, I have defined some technical words in the text. Occasionally I use order, family, or other levels of scientific classification. For readers unfamiliar with these terms, please see the appendix.

The discussions of various animal behaviors are not meant to be rigorous scientific reviews, nor are they meant to be exhaustive. I have opted for breadth rather than depth. I encourage readers seeking more information to consult the references, which range from general articles written for the nonbiologist to textbooks and technical scientific papers.

Join me in celebrating the diversity of nature with some amazing animal behaviors, from various insects and birds that offer food as bribes for sex to sac-winged bats that blend their own aphrodisiacs from urine and smelly glandular secretions.

Acknowledgments

WE THANK OUR editor, Christie Henry, for her insight and enthusiasm throughout this project. In addition, we thank Erin DeWitt of the University of Chicago Press for expert copyediting.

Members of Marty's weekly writing groupMartha Blue, Carol Eastman, Kay Jordan, Carol Maxwell, Mona Mort, and Marilyn Taylornot only tolerated a scientist in their midst; they also offered support and guidance from their nonbiologist perspectives. Karen Feinsinger and Judy Hendrickson provided additional helpful comments and suggestions on the text. Peter Feinsinger read and commented on the entire manuscript not once but twice; Marty thanks him for his suggestions, support, and encouragement.

Alan thanks Irma Crump for her thoughtful and creative suggestions, support, and patience when he was lost in the inkwell.

We applaud and are grateful to the many naturalists and scientists who recorded their fascinating observations of unusual animal behavior.

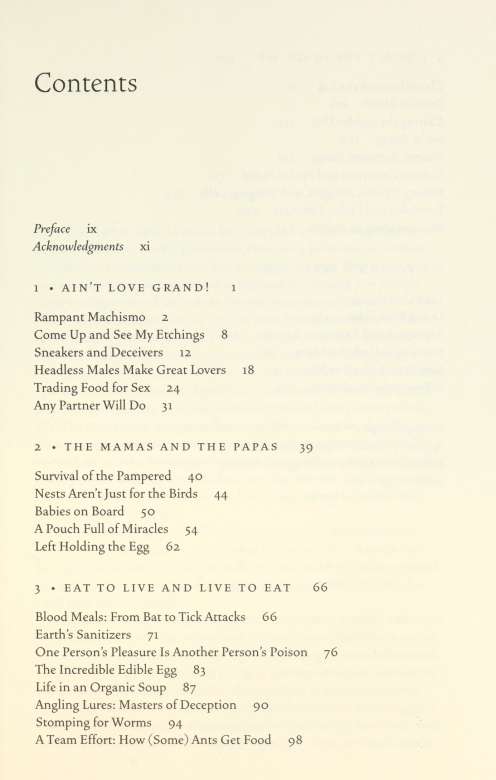

1 Ain't Love Grand!

PEOPLE OFTEN ASSUME that the evolutionary goal of copulating cats or mating monkeys is "to perpetuate the species." If this were true, males and females should approach mating cooperatively. Why then do we see so much hostility between the sexes? The goal is not to perpetuate the species but rather to perpetuate one s own genes. From the individual s standpoint, the goal is to produce as many offspring (and grandchildren, great-grandchildren, etc.) as possible. Individuals that leave behind the greatest number of descendants are the most "fit," and males and females differ in how they best increase their fitness.

The typical male strategy is to mate with as many females as possible, which often leads to fierce competition among males and requires elaborate displays to woo females. On the other hand, a female increases her fitness by mating with the "best" male available; she's choosy and rejects most suitors. Most females in a population mate, but often only a small fraction of the males mate.

The contrast in the ways males and females increase their fitness results from differences between their gametes (sex cells). A female produces relatively few large eggs that contain the resources needed for early development. Before a female's eggs are even fertilized, she has already made a substantial investment in each sex cell. In contrast, a male produces vast amounts of tiny mobile sperm. Consider humans. An average woman produces about 350 to 400 mature eggs during her lifetime. Each ejaculate from a healthy man consists of from 2 to 6 milliliters of sperm, each milliliter containing about 100 million sperm. For animals in general, a female's reproductive potential is much lower than a male's because she produces many fewer gametes. A female can hardly afford to waste her sex cells; a male can sow widely and often.

Throughout this chapter, we'll look at various ways animals attempt to increase their fitness: (1) competition among males, from bull elephant seals defending harems to male tiger salamanders tricking other males

2 | CHAPTER ONE

into depositing (and wasting) their packets of sperm; (2) elaborate male courtship to woo females, from nuzzling and dancing spiders to bugling elk; and (3) female choice of males, sometimes based on unusual criteria such as a male s fishing ability.