Mind

A Unified Theory of Life and Intelligence

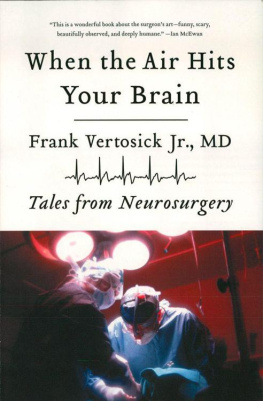

Frank T. Vertosick, Jr.

In memory of Robert H. Kelly,

colleague and friend

And this secret spake Life herself unto me:

Behold, said she, I am that which

Must ever surpass itself.

Friedrich Nietzsche,

Thus Spake Zarathustra, 1883

Preface

2014 Edition

When The Genius Within: Discovering the Intelligence of Every Living Thing was published in 2002, readers and reviewers familiar with my work may have expected an anthology of cute stories about exceptionally smart animals, like a dolphin capable of arithmetic perhaps, or a piano-playing squirrel. The book does contain stories of smart beasts, but none named Flipper or Rocky. The brilliant creatures extolled here are bacteria, immune cells and ant colonies. The genius of humans is barely mentioned. I was interested in the overall genius of life itself.

My book, renamed MIND: A Unified Theory of Life and Intelligence for this edition, challenges our entrenched brain chauvinism, the delusion that all intelligent machines must be hardwired, speak some language, use numbers, and operate at nanosecond speeds. We search for intelligent life on other worlds, meaning a kind of life that thinks exactly as we do. In our world, to be smart means to manipulate symbols, employ rules, and use formal logic. But in biology, thinking can be done statistically over vast scales of time and space. Life creates its own peculiar rules and adaptive logic in its quest to stay one step ahead of competitors and an ever-changing environment. We are convinced we are the smartest creatures to exist on earth. Yet I would bet my mortgage money on a pond amoeba, given the right IQ test. Einstein reminded admirers that genius is relative to the problem; despite his expertise in four-dimensional tensor calculus, the Father of Relativity would defer to the local mechanic to fix a bad transmission.

An ovum made us, and an ovum is like an amoeba. Well, thats not entirely true; this analogy actually insults the amoeba. An amoeba has ten times more DNA than the human egg and is two-hundred and fifty times larger. Yet the ovum is hardly dimwitted. It is said that the ovum contains the blueprints for a human being. Thats an understatement. The ovum contains the blueprints, the laborers, the bulldozers, the union contracts, the zoning permits, the payroll department, and everything else needed to assemble itself into a body, then age and die on schedule.

We are basically still cells; a body is one stage in a cells life cycle. To mate, the cell must seek another cell. People dont have babies, and cats dont have litters. That is an illusion; cells mate with cells to produce cells. Cells assume the forms of multicellular machines as a survival strategy, but when cells mate, they return to their true, pure states. Egg and sperm shed their disguises as human bodies just long enough to join. Their fusion will start building its own multicellular machine.

In the year that The Genius Within appeared, I was diagnosed with Parkinsons disease (YOPD) and had to retire from surgery. There were many pressing issues in my life, and although the book was well received critically, my focus was diverted, and I let my precious book gather dust. Now, thanks to Richard Curtis at E-Reads and my agent Victoria Pryor, it is being released as an e-book to a fresh audience. It may fall flat again, but at least this time my attic will stay uncluttered.

I dedicate this edition to Jane Isay, the books first editor at Harcourt, and one of the stalwarts in the book industry who have the courage to put quality above all else.

(Spoiler alert: those who have not yet read the book may wish to defer reading any further here.)

The book introduces five novel ideas that serve as reference points for discussing the science involved: 1. there is a unified theory of the living mind equivalent to the Theory of Everything in physics; 2. life has always been intelligent; 3. amoebas may be the smartest things on the planet;

4. all intelligence is based on the Darwinian principle of trial and error, though life has harnessed the power of natural selection to the point where evolution is itself evolving, making the trial and error method faster, less random and more powerful; 5. the sum of a species' ability to think across generations (genetic intelligence) and its ability to think within one organism (neurological intelligence) is the same in any species at any point in history. Flies have small brains but spawn a thousand generations in the time it takes for brainier beasts like us to have one. Insects can solve problems with their genes as fast, or faster, than we can with our nerve cells. Life is about solutions and survival; how a species solves problems is immaterial as long as the problems get solved.

Idea 1 asserts that the same rules that transform a collection of enzymes into a living cytoplasm also transform nerve cells into thinking brains, bacterial cells into computational engines; lymph cells into smart immune systems, ant hills into superorganisms, and so on. That set of rules, like the genetic code, is so unique and fundamental to the life process that it could not be invented twice.

Idea 2 flows from the first: life is intelligence at the molecular level, and you cant have one without the other. The living process is like a salmon swimming against the entropy stream. A real salmon needs brawn to fight the current, but life needs a brain. The brain of life is a bootstrapping machine that must solve the problems it creates by its own existence.

Idea 3 contends that single cells may be the smartest things on the planet, and that includes bacteria. They are simpler than our cells but reproduce more quickly, giving them rapid adaptability. We are learning that microbes form problem-solving societies, just as larger cells and animals do.

Idea 4 states that all thinking involves some element of Darwinian trial and error: try one solution, and if that fails, try again in a different way. We wrongly view trial and error as a brute force way of thinking. Thats true only when errors are corrected randomly. Trial and error becomes very powerful, however, if we use the error of each trial to improve chances of success with the next trial. When first learning to balance on a bicycle, for example, a person learns to make corrections in a direction and magnitude opposite to the error. As our errors get smaller, our corrections get smaller. Mutations are errors in the cells world, a form of noise that garbles the genetic message between generations. Living things soon recognized this and began correcting mutational errors in a purposeful way, too. Cells became so good at correcting mistakes that they made trial and error their chief way of solving problems.

All cells can change their rate of mutation intentionally to some degree, thus altering the nature and rate of their own evolution. Bacteria and immune cells at war during an infection can cram a million years of evolution into a few weeks. The ability to increase the trial rate and better ways of directing mutations to the genes that need to change fastest has made evolution no longer the blind watchmaker it once was.

As a network grows in size, it may reach a criticality point where an unexpectedly large and altered kind of intelligence suddenly springs forth; the collective mind suddenly becomes vastly more than the sum of its parts. I have been accused of calling this event, known technically as emergence, as akin to