Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

For Susi

Perhaps the easiest way of making a towns acquaintance is to ascertain how the people in it work, how they love, and how they die.

Albert Camus, The Plague

Contents

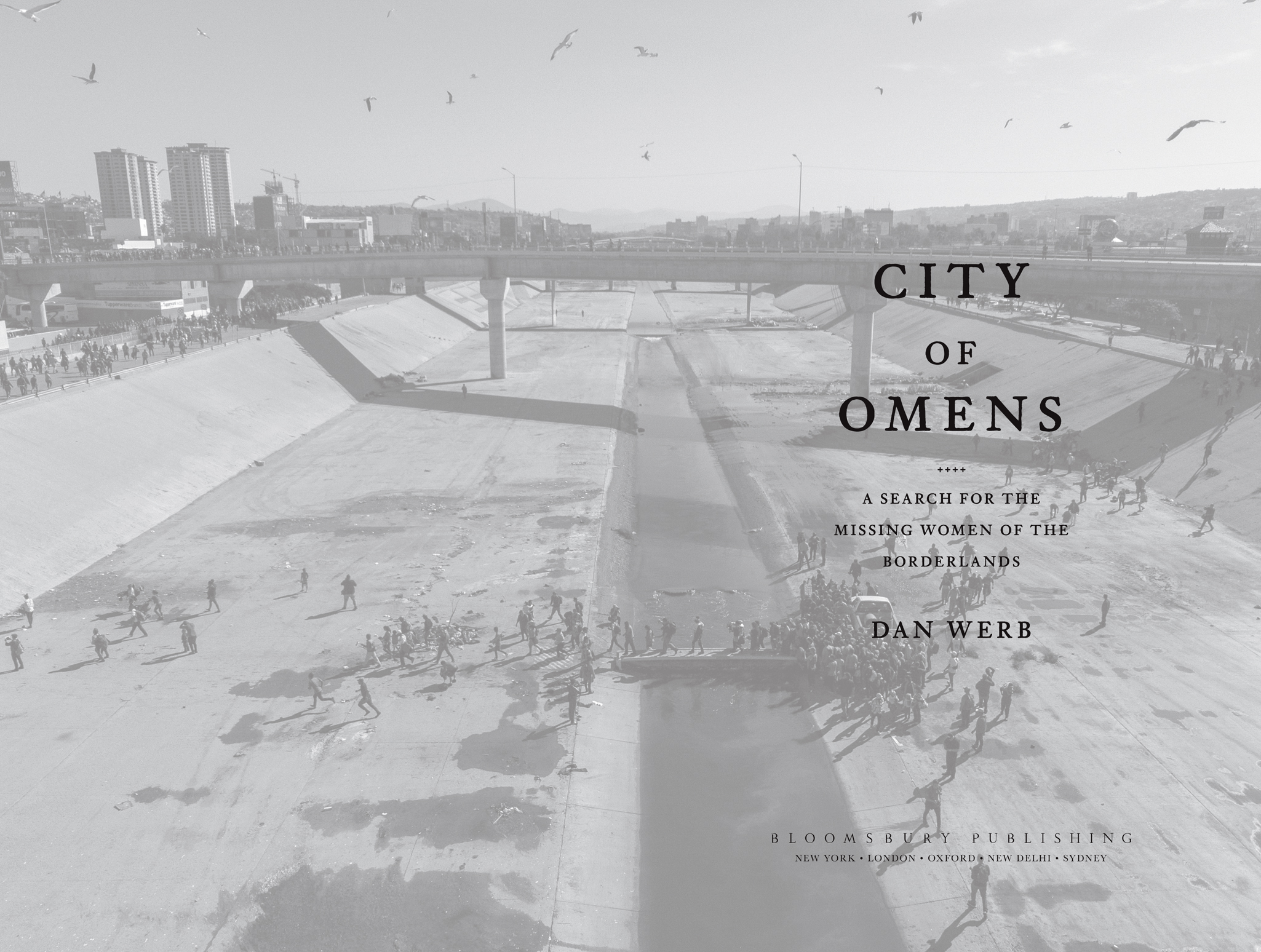

I stood in the middle of the Jack in the Box parking lot, looking around anxiously, sweating under the desert sun. I had worn slum-appropriate clothing, or at least a facsimile of what I thought that meant: blue button-down shirt, jeans, and cheap sneakers. The plan, I had been told, was to blend in. All around us were slow-moving cars, slow-moving pedestrians, and the sustained clatter and low horn blasts of the trolleys heading in from downtown San Diego, filled with people crossing the border, all with their reasons. Everybody looked at home in the sun, belonged to the space, while the heat beat down on me relentlessly.

Leaning against a Mercedes, Argentina, in pale immaculate makeup, didnt care whether she blended in or not. In stiletto heels, tight white pants, and a white fur shawl, she scanned the small parking lot, cased me right away, and shook my hand impatiently as we got into the car and then set off for Mexico. She was a young Mexican medical doctor and had been asked to transport me safely across the border and hand me off to those who would take me into the canal. We sat on chestnut leather seats as we sped through the border line and into Tijuana. We were waved through quickly, and as we entered Mexico, hundreds upon hundreds of cars and people came into view, stacked interminably on the other side of the wall, all waiting to be let into the United States of America.

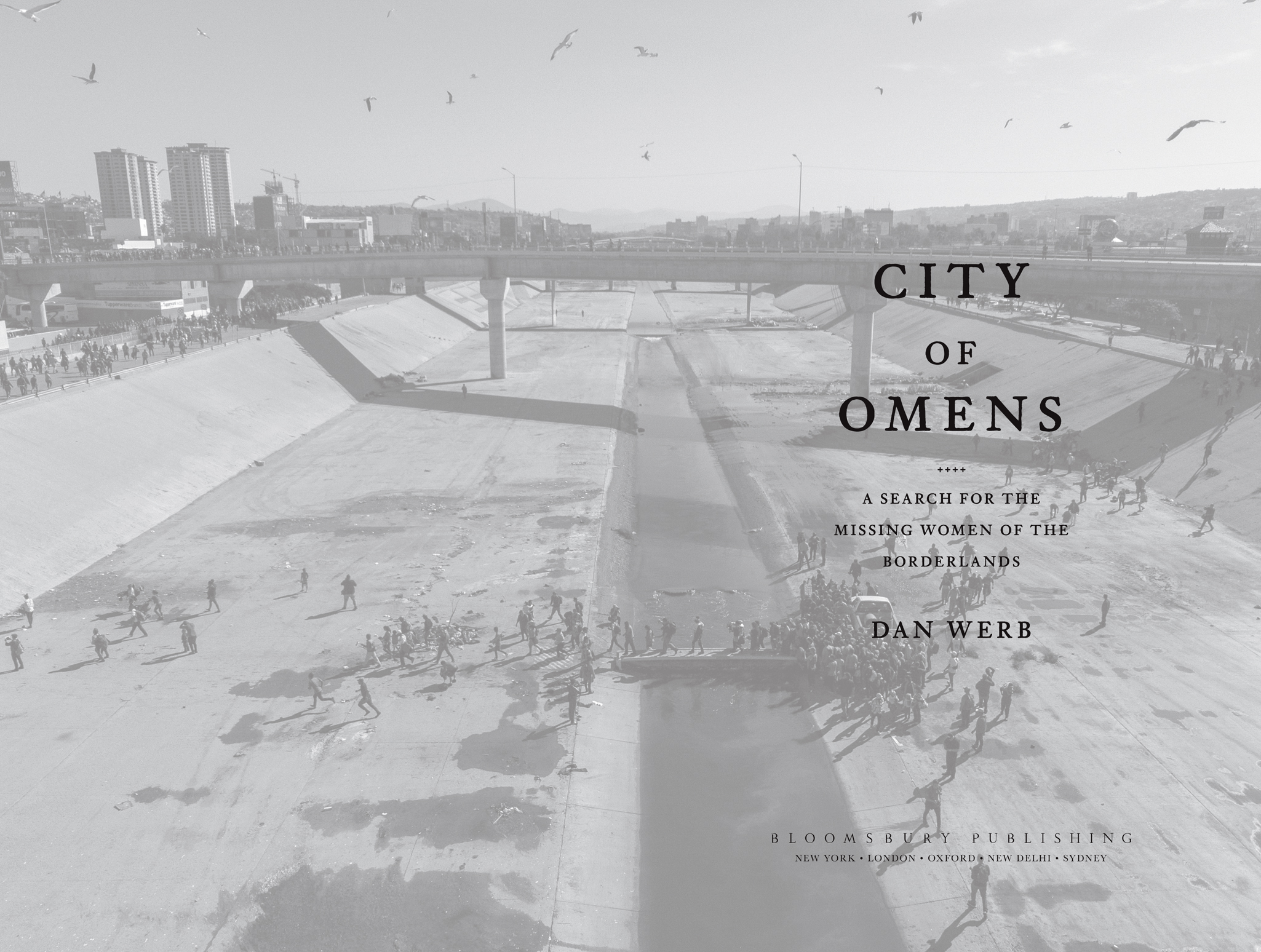

Its the first thing you see once you pass through the border line: the abandoned Tijuana River Canal, stretching north past the border fence and south through the city until there is no city left. Theres no way to avoid it. If you want to get downtown, you have to cross a bridge to get over it. If you want to skirt it, you have to drive down a highway, the Va Rpida, which snakes along both its sides for miles and miles, all the way to the citys southern limit. Its a barrier, a listless concrete space, appearing empty except for garbage and a thin trickle of sewage, engineered to be as inconspicuous as possible. As Argentina and I zoomed across a bridge in the white Mercedes, I let my eyes follow the wastewater seeping north along the canal floor below us. From my vantage point, I could see the brackish and brown pollution, just barely water, flashing under the white sun, but I could not tell where the stream flowed after the canal abruptly hit the border wall. The whole place looked like a no-mans-land, a static and determinedly empty negative space, the architecture devoid of shelter. And then something way down amid the concrete and refuse caught my eye: human beings.

Dr. Steffanie Strathdee, chief of the University of Californias Division of Global Public Health, had told me about the canal before I came to visit, and about its peculiar ecosystem. She was investigating how an HIV epidemic was spreading through the hundreds and perhaps thousands of people who inject drugs and live in rough encampments along the spaces low sloping walls. My job, she had explained, would be to help delineate the contours of the epidemic so that she and her colleagues could understand its spread and develop programsbehavioral interventions, social services, infrastructure, or some still unknown approachto contain it.

I had come to the border from Vancouver, Canada, where I was finishing up my PhD in epidemiology and biostatistics after a short stint as a freelance journalist on the drug addiction beat. My graduate studies were defined by the behavior, tracked over eight years, of a sample of people who inject drugs in Vancouvers Downtown Eastside neighborhood, a place that is home to one of North Americas largest open-air illegal drug markets. I had published some scientific findings about the neighborhood and the people who lived there, most of which focused on the destructive impact of policing among the samples drug-injecting participants, which ratcheted up their risk of sharing contaminated needles and becoming infected with HIV. I was proud of the work, but I was also itching under the steady hands of my mentors and searching for my next move. It felt like I had taken research on my hometown as far as it could go.

I had first met Steffanie in 2006, the year I started working as an assistant at an HIV research center in Vancouver. At the time, my desk was in a dead-end hallway far from my colleagues. It was lonely there except when Steffanie and her husband, Tom Patterson, breezed in, every two months or so, to do some kind of consultancy work with my superiors. On one of those visits we got to talking andin the scholarly equivalent of a first dateI asked Steffanie if shed co-author a scientific manuscript I was writing (she agreed). She was smart, but more important, she was supportive, and she never seemed stressed out. I liked that combination. As the years progressed and I thought about my next career move, the idea of working more closely with someone as breezy and relaxed as Steffanie, and doing it in the sunshine of Southern California, became more and more appealing. By 2012, when I was a year away from finishing my PhD, we started talking seriously about me joining her team after I defended my thesis. Before I made up my mind, though, she wanted me to come down to Tijuana.

By that point, I was familiar with shock tourism, having lived or worked in Vancouver most of my life. People come to the Downtown Eastside to feel the thrill of outsider existence, of experiencing by osmosis the desperation and poverty of the people who live there, many of whom inject drugs in the neighborhoods chaotic alleys in full view of passersby. Ive felt it myself: that yearning to parachute into a place where cops are ubiquitous, neck injections with dirty puddle water are the norm, and optimism is scarce. I understand the urge to step out of a car and wander around a place you dont understand for an afternoon (but not a minute longer). It is, of course, nothing more than a fantasy of belonging. But its hard to resist the feeling that a kernel of truth has been passed from those who are suffering to those who have come to watch them, as if mute observation is an act of charity. When I took Steffanie up on her invitation, I vowed to avoid the temptation to treat Tijuana like a dark and titillating ride, and instead recognize the visit for what it was: a scientific excursion into a field research site beset by a public health crisis.

Perched above the Tijuana River Canal in the Mercedes, I tried to decipher what the small human shapes moving below us were doing, but Argentina revved the motor again and we were quickly away. We maneuvered off the bridge, cut into a busy road, and zigzagged across downtown Tijuana, the traffic moving against pedestrians with predatory intent. As we pulled into the driveway of a health clinic where Argentina was a volunteer, it hit me that I had completely lost my sense of direction. With the border wall having receded from view, I stepped cautiously out of the car, trying in vain to find some touchstones. Before I could get my bearings, Argentina gave me a quick wave and promptly roared off, starting her day in earnest, the delivery complete. She had more important things to do. I was handed to someone else whose name I dont remember, escorted into another car full of people, and shuttled off again. We were finally heading to the field research headquarters for Proyecto El Cuete (the Needle Project), Steffanies research study, in the heart of the Zona Norte, the neighborhood that is pressed up against the border fence and encompasses Tijuanas red-light district and the northernmost portion of the citys canal.