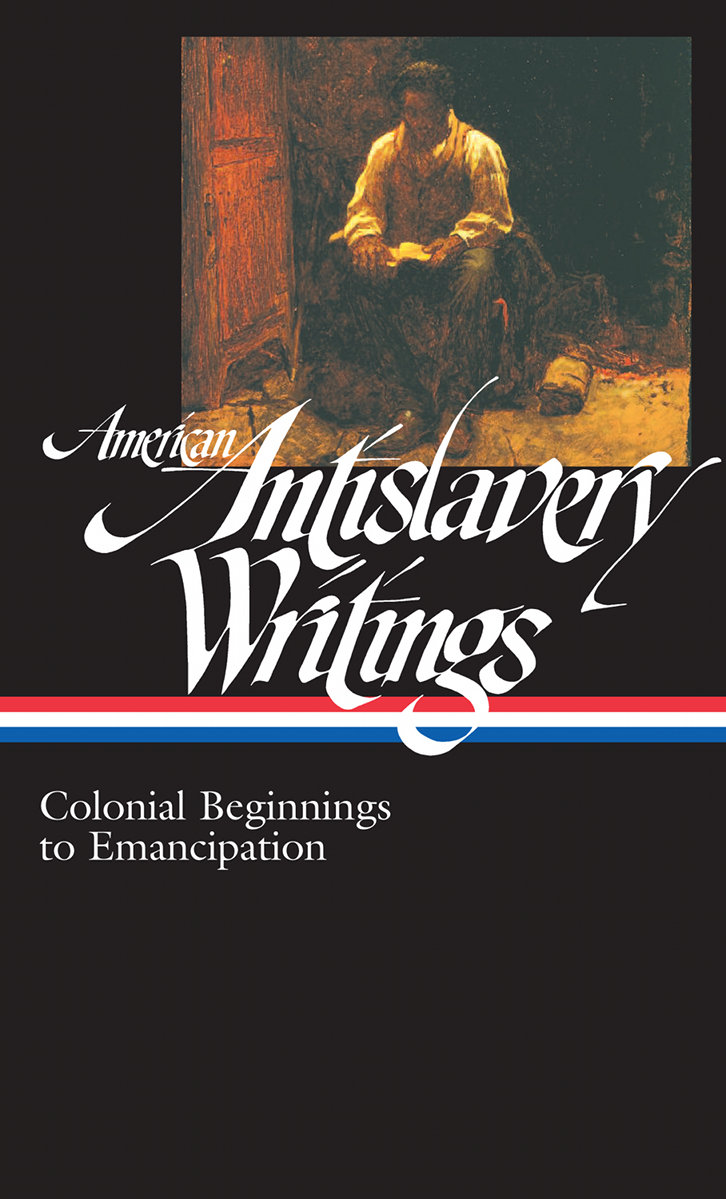

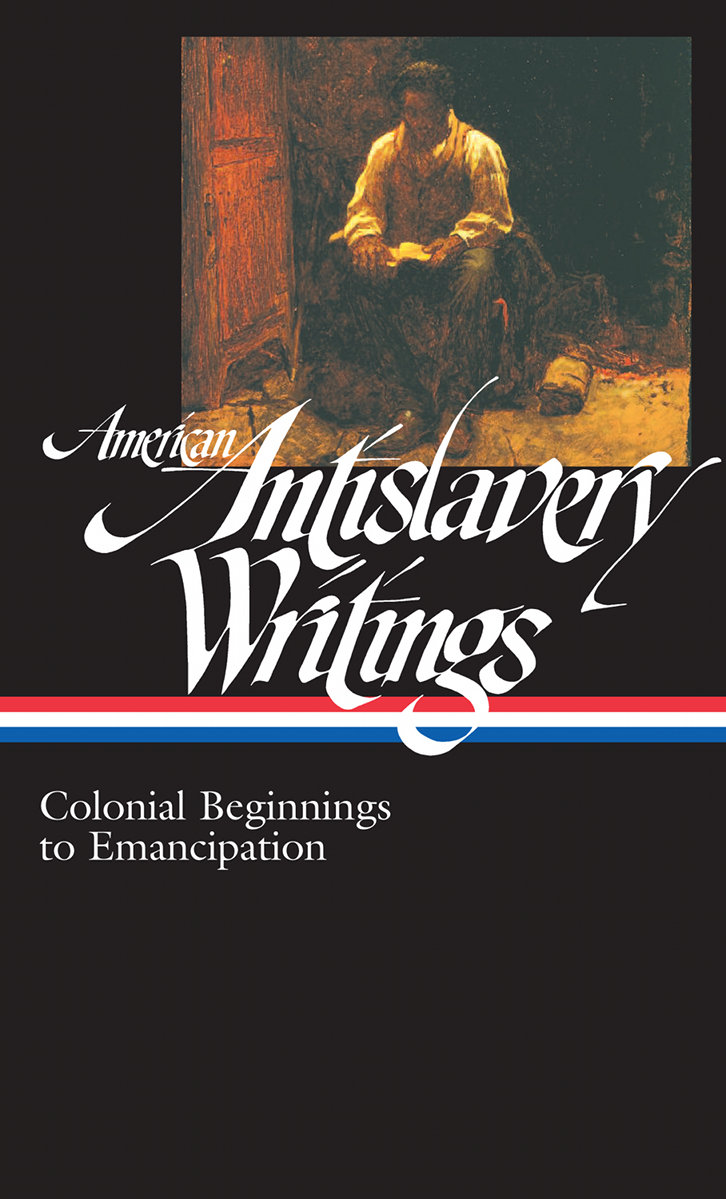

AMERICAN

ANTISLAVERY WRITINGS

COLONIAL BEGINNINGS

TO EMANCIPATION

James G. Basker, editor

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA

Volume compilation, introduction, notes, and chronology

copyright 2012 by Literary Classics of the

United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of the book may be reproduced commercially by offset-lithographic or equivalent copying devices without the permission of the publisher.

Some of the material in this volume is reprinted by permission of the holders of copyright and publication rights. See Note on the Texts on page 901 for acknowledgments.

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of Americas best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

If you would like to request a free catalog and find out more about The Library of America, please visit with your name and address. Include your e-mail address if you would like to receive our occasional newsletter with items of interest to readers of classic American literature and exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors (we will never share your e-mail address).

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012935173

ISBN 9781598532142 (epub)

American Antislavery Writings:

Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation

is kept in print by a gift from

SIDNEY AND RUTH LAPIDUS

to the Guardians of American Letters Fund,

established by The Library of America

to ensure that every volume in the series

will be permanently available.

American Antislavery Writings:

Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation

is published with support from

THE ANDREW W. MELLON FOUNDATION

and

GILDER FOUNDATION

Introduction

One of the best-selling books in history, Uncle Toms Cabin was indeed tremendously significant, but its importance has sometimes obscured an essential point: Stowes 1852 novel was only the most celebrated manifestation of a complex and diverse tradition of American antislavery writing that stretched back more than one hundred and fifty years.

As the volume before you attests, by the end of the seventeenth century writers such as Gerret Hendricks and George Keith in Pennsylvania and Samuel Sewall in Massachusetts had already publicly voiced their opposition to slavery, laying the groundwork for hundreds of other writers who would follow in a broadening current that by the 1850s would encompass whole shelves of literature in every genre. One marker of the significance of this tradition is the reactions it provoked from slaverys defenders, which often went far beyond words. In 1829, after David Walker published his rousing Appeal, calling on fellow African Americans to resist slavery and discrimination, distributors of his book in Charleston and New Orleans were arrested, and the Georgia legislature offered a reward of $10,000 for Walker delivered alive, or $1,000 dead. In 1837, a proslavery mob in Alton, Illinois, killed the antislavery publisher Elijah Lovejoy and destroyed his printing press. A year later, after a speech by the abolitionist Angelina Grimk in Philadelphia, a mob sacked the hall in which she had spoken and started a fire that consumed the building, which also housed the newspaper offices of fellow abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier, himself the victim of mob threats on other occasions. And in 1856 the violence reached the seat of power itself, when South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks responded to Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumners speech The Crime Against Kansas by beating him unconscious with a cane on the floor of the Senate.

These episodes of censorship and violence suggest the problem for slaverys advocates: despite various political victories, over the long run they were losing the battle of ideas, a trend dramatically accelerated by the coming of the Civil War. A letter from a Union soldier in the midst of the conflict gives us another perspective on the spread of antislavery values and sensibilities. Writing to his wife from Tennessee on October 3, 1862, Lieutenant John P. Jones of the 45th Illinois Volunteer Infantry responded to the news of Lincolns preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, issued just eleven days earlier. The year of jubilee has indeed come to the poor Slave, he wrote. The proclamation is a deathblow to Slavery.... It is what I have expected and what I have hoped for. We now know what we are fighting for, we have an object, and that object is avowed.... Oh! what a day for rejoicing will it be, when America the boasted land of the free and home of the brave shall have erased from its fair escutcheon the black Stain of human Slavery. The arrival what might have predisposed so many to embrace the war as a crusade against slavery?

As the first pieces in this anthology suggest, arguments against slavery had been circulating in the colonies for eight decades before the American Revolutioneven in the writings of men who were slaveholders themselves, such as the Virginians Arthur Lee and Patrick Henry. Slavery troubled the consciences of many Americans from the beginning. On June 19, 1700, Massachusetts merchant and magistrate Samuel Sewall wrote in his diary: Having been long and much dissatisfied with the Trade of fetching Negroes from Guinea... began to be uneasy that I had so long neglected doing anything. Seventy-six years later, in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence, another ambivalent Virginia slave-owner, Thomas Jefferson, denounced the slave trade as an assemblage of horrors and cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberty, and blamed the British for inflicting it on the American colonies in the first place. The others on the drafting committeeJohn Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert R. Livingston, and Roger Shermanagreed with him and approved the text. But then, in an early version of a conflict that would play itself out repeatedly, delegates from Georgia and South Carolina objected, causing the Congress to delete the passage about the slave trade in the interests of union and harmony. The issue was deferred, but, as this volume powerfully shows, it did not go away. Instead, antislavery writing emerged as one of the most energetic, voluminous, and transformative traditions of literature in the history of American letters.

There are no easy generalizations about this body of writing. The 216 selections by 158 different authors presented here, chosen from thousands of others, include works in every genre, ranging from poems, plays, novels, and short stories to slave narratives, orations, editorials, essays, letters, and petitions, as well as sermons and childrens books. Writers published their efforts in every form and medium, from handsome multivolume novels and thick tracts and plays for the stage to shorter pieces and single poems printed in pamphlets, anthologies, song books, childrens primers, magazines, and newspapers. The authors themselves are strikingly diverse: white and black, male and female, southern and northern, wealthy and poor, educated city-dwellers and rural autodidacts, amateurs as well as professional writers. It is the democratic inclusiveness of this literature, almost as much as its revolutionary content, that marks it as so surprising, so worthy of our attention.

Next page