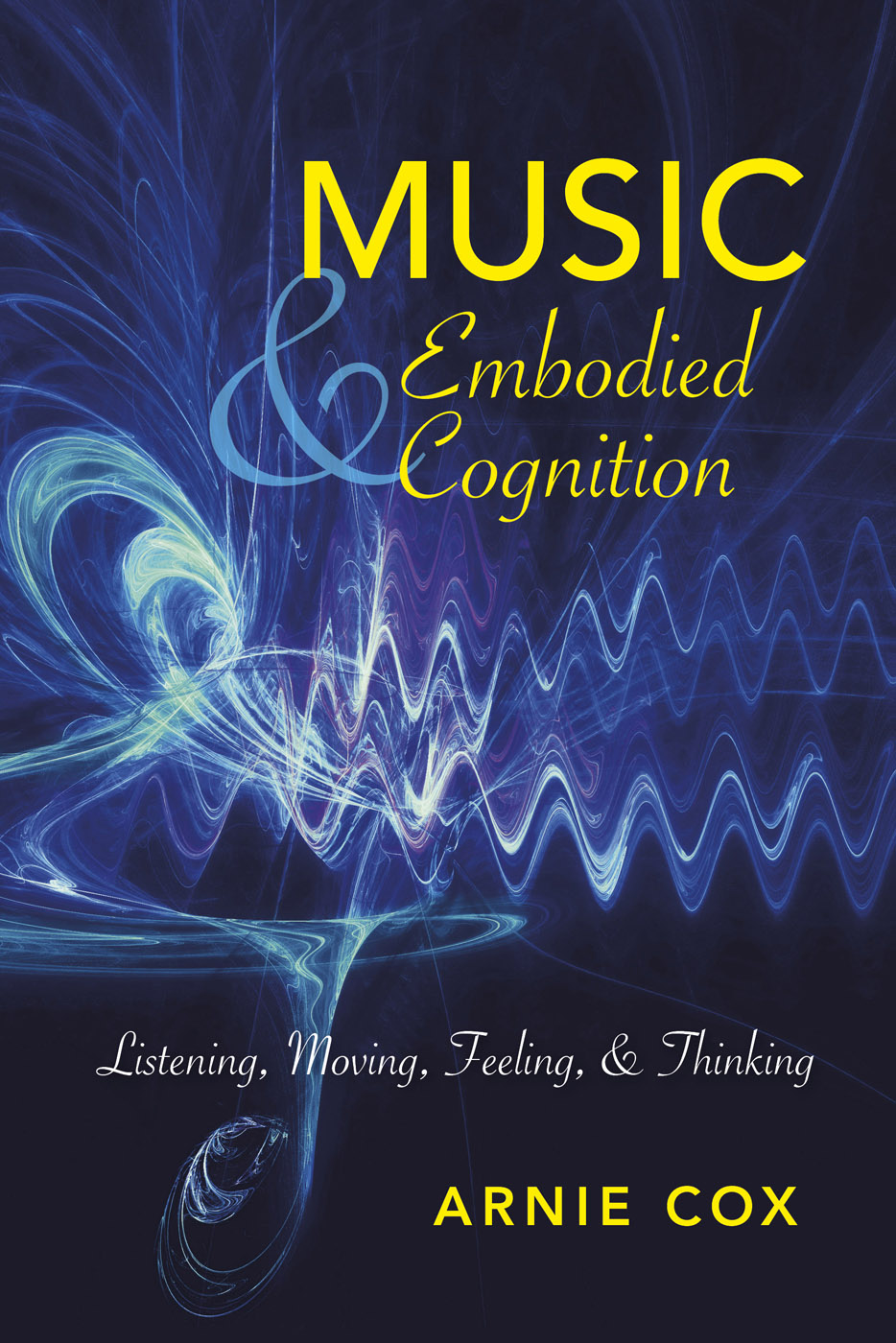

Music and Embodied Cognition

Music and Embodied Cognition

Listening, Moving, Feeling, and Thinking

ARNIE COX

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Bloomington & Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2016 by Arnie Cox

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cox, Arnie, 1963- author.

Title: Music and embodied cognition : listening, moving, feeling, and thinking / Arnie Cox.

Other titles: Musical meaning and interpretation.

Description: Bloomington ; Indianapolis : Indiana University Press, 2016. | 2016 | Series: Musical meaning and interpretation | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016004456 | ISBN 9780253021601 (cloth : alkaline paper)

Subjects: LCSH: MusicPsychological aspects. | Emotions and cognition. | Emotions in music. | MusicPhilosophy and aesthetics.

Classification: LCC ML3830 .C69 2016 | DDC 781.1/1dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016004456

1 2 3 4 5 21 20 19 18 17 16

Contents

Acknowledgments

My music studies began in the public schools under Vernon Ludwig and Jim Reynolds; my professional life as a music teacher and scholar has been possible only because of the existence of such programs and the efforts of these educators. In my undergraduate studies at Humboldt State University I was fortunate to learn from Frank Marks, Charles Moon, Hubert Kennemer, and our instrument technician and mentor-in-residence Dan Gurne, each of whose encouragement and lessons have contributed to the ideas in this book.

I encountered two scholars during my graduate studies at the University of Oregon whose influence provided the most direct and substantive foundation for this book. Nadine Hubbs was a visiting member of the music theory faculty at the time, and while introducing me to the breadth of alternatives and complements to structural music analysis she directed me to the work of Mark Johnson, who, as it happened, had recently accepted a position as chair of the philosophy department across campus. Marks interest in the bases of musical meaning led to a very beneficial collaboration, and Im grateful for his guidance and encouragement, from my coursework and dissertation to the eventual book.

I would also like to acknowledge the help and educational benefits of studying with my other teachers at the University of Oregon: Peter Bergquist, Jack Boss, Robert Hurwitz, Dean Kramer, Steve Larson, Harold Owen, and Marian Smith.

Since arriving at the Oberlin College Conservatory of Music my ideas have been shaped through conversations with many current and former colleagues, in particular Tim Best, Rebecca Leydon, Charity Lofthouse, Joe Lubben, and Diane Urista. Colleagues at other institutions who have been especially helpful include Candace Brower, Murray Dineen, Marion Guck, Eric McKee, Janna Saslaw, Mari Takada, and Larry Zbikowski.

I have refined most of the ideas in this book in the context of my teaching, and the feedback from my students is reflected throughout the following chapters. First among these is Kendra Juul, whose analysis of Bjrks Enjoy confirmed early on my belief in the value and practicality of the kind of holistic analytical approach that eventually became what is outlined here in start of my time at Oberlin, Lucy (Davis) Vander Kamps ideas and encouragement were especially helpful.

I am grateful that Indiana University Press and the Music and Meaning Series under Robert Hatten took an interest in this project. I want to thank Robert for his comments, questions, and suggestions with regard to the manuscript, along with Elizabeth Margulis for her comments and suggestions on behalf of Indiana University Press. I would also like to thank Raina Polivka and Janice Frisch at Indiana University Press for their encouragement and help in the process, and Candace McNulty for insightful questions and comments along with the copyediting.

Finally, I would like to thank two longtime friends, Dave Pinyerd and Adrienne Valencia, for listening, offering feedback, and otherwise supporting me as I tried out various ideas over the last two decades. And my parents: Sylvia (Lavell) Cox, who most often went by Toby and who had the most beautiful soprano voice one could wish to hear, and Rod Cox, who cant carry a tune in a bucket, as he would say, and yet loves to sing. They encouraged my music studies from the first lessons through graduate studies and beyond, and they fostered in me a perspective that is woven into the fabric of the following pages.

Music and Embodied Cognition

Introduction

I do not know how the sentence

I have a body is to be used.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Like many music students, I spent a good deal of my undergraduate and graduate coursework in music theory focusing on musical structure and making more or less factual observations about how the various elements of music fit together in particular works and styles. Since I enjoyed this kind of study, for my doctoral thesis I planned to take the same approach in analyzing the music of Debussy. But then one day the stove in my apartment stopped working, the repairman came over, and we started chatting. He asked if I was a student up at the college, and I said yes, and that I was studying music theory. He replied, with unexpected enthusiasm and seriousness, Music theoryso you must study how music makes us feel things. With some embarrassment I explained that I was actually studying hierarchical relations among musical tones, at which point our conversation quickly died a quiet little death. His assumption, however, that a music theorist naturally would study musical affect led me to reflect on my scholarly priorities. One result of this reflection was my attention to the fact that, although my analysis revealed relevant and interesting details about the music, it seemed to miss something important about how the music works and about why I was drawn to this music in the first place. From this reflection emerged a desire for a more holistic approach.

My search for a more holistic, interpretive approach led me to Debussys letters and critical writings, where I intended to learn what I could about how he understood his own music and the music of others. Since these writings proved to be filled with metaphors, both conventional and idiosyncratic, I then needed a way of understanding more explicitly the relationship between his words and the music to which they referred. I eventually settled on conceptual metaphor theory, and the book you are reading is a result of my study of the relationship between musical experience and conceptualizationor, how music makes us feel and think whatever it is that it makes us feel and think. This exploration has led me beyond the music of Debussy to a number of principles that apply to music generally, some of which are directly in line with the repairmans assumption, and some of which lead to still more questions.

Next page