Prakash - Mumbai Fables

Here you can read online Prakash - Mumbai Fables full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Harper Colllins, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Mumbai Fables

- Author:

- Publisher:Harper Colllins

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mumbai Fables: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Mumbai Fables" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Prakash: author's other books

Who wrote Mumbai Fables? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Mumbai Fables — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Mumbai Fables" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

MUMBAI FABLES

Gyan Prakash

HarperCollins Publishers India

New Delhi

For Aruna

Contents

FIGURES

PLATES

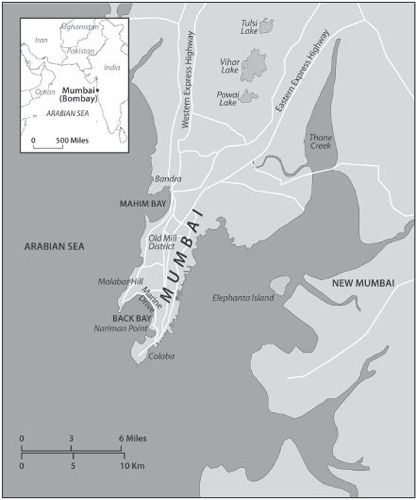

It is just before two oclock in the afternoon in April, the hottest month of the year. A tiny speck appears in a cloudless Poona sky, moving steadily toward the Tower of Silence, the funerary place where the Zoroastrians expose their dead to be consumed by birds of prey. It is not an eagle; nor is it a crow, for it could never fly that high. As the speck approaches the tower, its outline grows larger. It is a small aircraft, its silver body gleaming in the bright sun. After flying high above the Parsi place of the dead, the plane disappears into the horizon only to double back. This time, it heads determinedly to the tower, hovers low over it, and then suddenly swoops down recklessly. Just when it seems sure to plunge into the ground, the plane rights itself and flies upside down in large circles. A bright object drops from the aircraft into the well of the tower, illuminating the structure containing a heap of skeletons and dead bodies. As the light from the bright flare reveals this gruesome sight, the plane suddenly rights itself and hovers directly overhead. The clock strikes two. A camera shutter clicks.

The click of the camera shakes the Zoroastrian world. The Parsi head priest of the Deccan region, taking an afternoon nap, immediately senses that foreign eyes have violated the sacred universe of his religion. Parsi priests, who are performing a ritual at their Fire Temple, feel their throats dry up abruptly and are unable to continue their chants. As the muslin-covered body of a dead Parsi is being prepared for its final journey to the tower, the deceaseds mother suddenly lets out a piercing shriek. When the sacred fire burning at a Zoroastrian temple bursts into sparks, the assembled priests agree that a vital energy has escaped the holy ball of fire.

T hus begins Tower of Silence, an unpublished novel written in 1927 by Phiroshaw Jamsetjee Chevalier (Chaiwala), After setting the scene of this grave sacrilege to the Zoroastrian faith, the novel shifts to London. On the street outside the office of the journal The Graphic is a large touring Rolls-Royce, richly upholstered and fitted with silver fixtures. In it sits a tanned young man in a finely tailored suit, with a monocle in his left eye. He is Beram, a Parsi who blends the knowledge of the shrewd East with that of the West and is a master practitioner of hypnotism and the occult. He is in London to hunt down and kill those who have defiled his religionthe pilot who flew the plane over the tower, the photographer who clicked the snapshot, and the editor who published it in The Graphic. This locks him in a battle of wits with Sexton Blake, the famous 1920s fictional British detective, and his assistant Tinker, who are employed by the magazine. As Beram goes about systematically ferreting out his intended victims, with Blake and Tinker in pursuit, the novel traverses London, Manchester, Liverpool, Burma, Rawalpindi, and Bombay. It concludes with Parsi honor restored.

In Chaiwalas thrilling fable of Parsi revenge, the protagonists slip in and out of disguises and secret cellars. They follow tantalizing clues and leave deliberately misleading traces, practicing occult tricks and hypnotism to gain an advantage in their quest. Magic and sorcery, however, operate in a thoroughly modern environment. Industrial modernity, in the form of planes, trains, and automobiles, figure prominently. The high-altitude camera and the illustrated magazine reflect a world of image production and circulation. The novel travels easily between Britain and India and comfortably inhabits British popular culture. Imperial geography underwrites this space. Colonialism conjoins Britain, India, and Burma and produces the cosmopolitan cultural milieu that the novelist presents as entirely natural. Beram dwells in this environment while proudly asserting his religious identity. He is no rootless cosmopolitan but a modern subject, deeply attached to his community. His quarrel with the pilot, the photographer, and the editor is not anticolonial. Chaiwala mentions the Gandhian movement against British rule, but Beram expresses no nationalist sentiments; his sole motivation is to right the wrong done to his faith by modernitys excesses, by its insatiable appetite to erase all differences and violate all taboos. He represents a form of cosmopolitanism that is based on an acknowledgment of cultural differences.

The novel bears the marks of its time, but it also presents a picture of Bombay that persists. This is evident as much in the depiction of the city, where Beram and Sexton Blake play their cat-and-mouse game, as in the whole imaginative texture of the novel. A Bombay man himself, Chaiwala celebrates the citys mythic image when he describes it as gay and cosmopolitan, a heady mix of diverse cultures and a fast life. Its existence as a modern city, as a spatial and social labyrinth, can be read in the detective novel form. The sensibilities and portraits associated with Bombay are inherent in the novels geographic space, in its characters and their actions.

When I came upon Chaiwalas typescript in the British Library, I found its fictions and myths resonate with my childhood image of Bombay. Cities live in our imagination. As Jonathan Raban remarks, The soft city of illusion, myth, aspiration, nightmare, is as real, maybe more real, than the hard city one can locate on maps in sta This is how Bombay, or Mumbai, as it is now officially known, artlessly entered my life. Bombay is not my hometown. I was born more than a thousand miles away in a small town named Haza-ribagh. I grew up in Patna and New Delhi and have lived in the United States for many years. Mine is not an immigrants nostalgia for the hometown left behind, but I have hungered for the city since my childhood. Its physical remoteness served only to heighten its lure as a mythic place of discovery, to sustain the fantasy of exploring what was beyond my reach, what was out there.

This desire for the city was created largely by Bombay cinema. Nearly everyone I knew in Patna loved Hindi films. Young women wore clothes and styled their hair according to their favorite heroines. The neighborhood toughs copied the flashy clothes of film villains, even memorizing and mouthing their dialogues, such as a line attributed to the actor Ajit instructing his sidekick: Robert, Usko Hamlet wala poison de do; to be se not to be ho jayega (Robert, give him Hamlets poison: from to be he will become not to be). No one knew which film this was from, or indeed if it was from a film at all. Ajits villainous characters were so ridiculously overdrawn that he attracted a campy following that would often invent dialogues. Then there were Patnas own Dev Anand brothers, all three of whom styled their hair with a puff, in the manner of their film-star idol. Emulating their hero, they wore their shirt collars raised rakishly and walked in the actors signature zigzag fashiontrouser legs flapping, upper body swaying, and arms swinging across the body. Like many others, I remember the comedian Johnny Walker crooning in Mohammed Rafis voice, Yeh hai Bambai meri jaan (Its Bombay, Darling) to the tune of Oh My Darling, Clementine, in CID (1956).

Hindi cinema stood for Bombay, even if the city appeared only fleetingly on-screen, and then too as a corrupt and soulless opposite of the simplicity and warmth of the village. I understand now that underlying our fascination with Bombay was the desire for modern life. Of course, the word

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Mumbai Fables»

Look at similar books to Mumbai Fables. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Mumbai Fables and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.