Contents

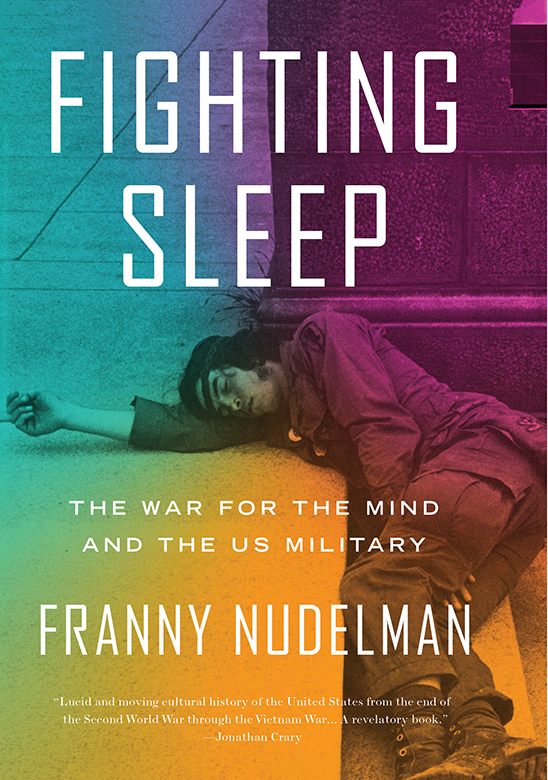

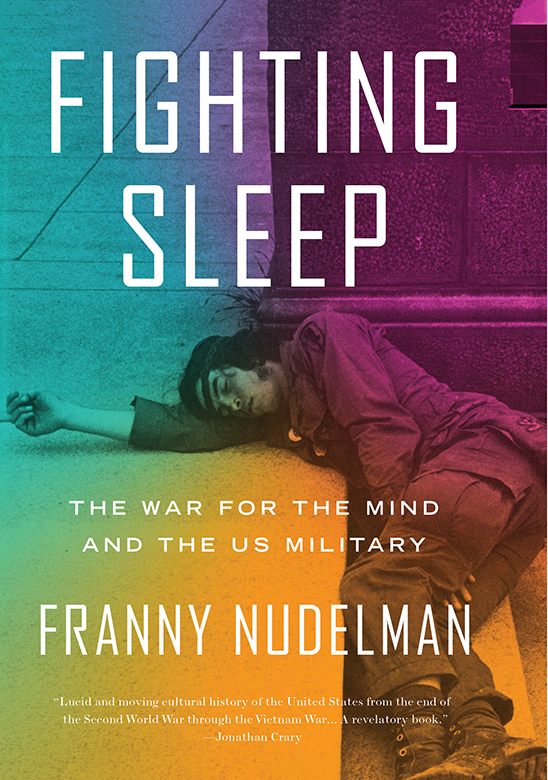

Fighting Sleep

Fighting Sleep

The War for the Mind

and the US Military

Franny Nudelman

First published by Verso 2019

Franny Nudelman 2019

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-781-9

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-784-0 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-783-3 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nudelman, Franny, author.

Title: Fighting sleep : the war for the mind and the US military/Franny Nudelman.

Other titles: Militarism and dissent in the age of expansion

Description: Brooklyn : Verso, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019018123| ISBN 9781786637819 (hardback : alk. paper) |

ISBN 9781786637833 (United Kingdom)

Subjects: LCSH: Vietnam War, 19611975VeteransPolitical activityWashington (D.C.) | Vietnam War, 19611975VeteransMental health. | Vietnam War, 19611975Protest movementsUnited States. | Sleep deprivationUnited States. | SleepSocial aspects. | Sleep disordersUnited States. | Post-traumatic stress disorderTreatmentUnited States. | SoldiersHealth and hygieneUnited States.

Classification: LCC DS559.73.U6 N83 2019 | DDC 959.704/31dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019018123

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

For David and Leo

Contents

Credit: Authors photo

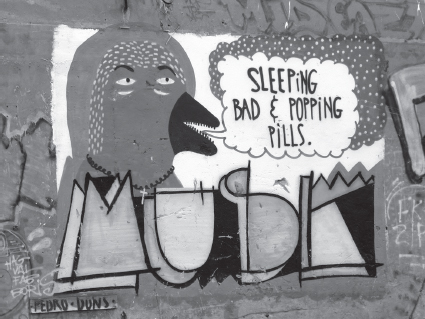

Sleeping Bad and Popping Pills, Berlin street art.

I grew up an insomniac in a household of insomniacs, where each day began with a discussion of the night before: How did you sleep? What time did you wake? Sleeping pill or no? As an adult, I was surprised that not everyone wanted to engage in lengthy conversation about the duration and quality of their sleep. For some people, sleep was no big deal, and this seemed strange to me. I envied my friends who could take sound sleep for granted, but at the same time noticed that they didnt seem to enjoy sleep the way I did. Indifferent to fine wine and gourmet meals, I am a sleep connoisseur; sensible to the finer aspects of my sleep while sleeping, there is little I enjoy more than a good nights rest.

Bad sleep was just one of the maladies that occupied us. My parents barely missed being hippieswe lived in the Haight-Ashbury the summer before the Summer of Lovebut still they cultivated the kind of anxious introspection that was one signature of the New Age. It was in San Francisco that my mom briefly tried her hand at abstract painting, and I recall in particular one canvas with a white field poised above an orange one, the two divided by a black line on which she wrote: The loneliness of the transplanted brain. I thought it was quite neat, not least because there was a tiny dollhouse mirror placed above the cryptic line. In the Bay Area, such malaise was bread and butter for a host of therapeutic professionals and spiritual guides, and my parents frequented counselors of every stripe, practiced transcendental meditation, attended weight-loss clinics, and on.

Their concerns over what we now call wellness extended, however, far beyond our home. During the 1970s, they became antinuclear activists and conversation in our house turned to apocalypse as often as it did to sleep. My dad, a doctor and early member of Physicians for Social Responsibility, gave lectures to antiwar groups about the dangers of nuclear arms, using photographs of Japanese victims in Nagasaki and Hiroshima to illustrate the effects of these weapons on the human body. My parents put their shoulders to the wheel, but at the same time they made it clear to me that their hopes for the planet were dim. In adolescence, my nightmares often involved the outbreak of nuclear war; in one such dream, as bombs detonated, a voice came over a loudspeaker to inform me that I was now losing all responsibility for self-awareness. For me, bad sleep is bound up with a moment in timea moment that belongs to my parentswhen the menace of war was unabashedly experienced by way of psychological complaint, and the struggle to end it allied with altering consciousness.

In the spring of 1971, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) fought the courts for the right to sleep on the National Mall as part of their weeklong demonstration, Dewey Canyon III. When the courts denied their petition, veterans decided to break the law by sleeping anyway. Turning good rest into a form of dissent, hundreds of veterans fell asleep, wondering whether or not they would be arrested by daybreak. Clearly, sleep played a part in the movement to stop the US war in Vietnam. Still, I wondered, why did the government see fit to let veterans stay overnight on the Mallsinging, talking, even lying downwhile refusing to let them fall asleep there? Why did veterans decide to sleep and risk arrest? This book began as my effort to understand what was at stake in this contest, and, from there, my story grew, traversing the fields of military and mainstream psychiatry, popular and institutional film, documentary sound technology, methods of brain warfare, and the tactics of postwar social movements to arrive back at the scene of soldiers sleeping soundly in the public square.

The VVAW sleep-in speaks powerfully in no small part because it flies in the face of a clinical and cultural record of war trauma that is rife with scenes of troubled sleep: the sleepless soldier and the insomniac veteran are protagonists of an evolving narrative of trauma and its aftermath that spans the course of the twentieth century. The recurring nightmares Troubled sleep emerges as a refrain in the psychiatric literature of war and functions as a metonym for postwar trauma in popular representations of soldiers and veterans.

Veterans radicalism engaged a history of military experimentation that used the sleep of soldiersdreams, insomnia, twilight sleep, nightmares, and flashbacksto explore and define the nature of trauma. In particular, during World War II, an epidemic of mental illness in the military helped to focus the fledgling field of psychology on the experiences of soldiers and made their sleep a special source of information. Drug-induced sleep served as a routine form of treatment and a means of inquiry and experimentation. Inducing deep and twilight sleep in clinical settings, military psychiatrists studied the effects of war violence on the soldiers mind. In the process, they redefined the nature of memory in ways that would have far-reaching influence, and pioneered techniques of brainwashing that would weaponize both memory and sleep.

Clinicians used sleeping soldiers to generate new knowledge not only about subjectivity but also about interrelationship. Patients underwent talk therapy while sedated in scenes of coercion and, strangely, co-creation that at times confounded the very boundaries of identity. Such experiments alert us to the role of interviews, dialogue, and conversation in producing ideas about how we remember and assimilate extreme events and experiences; questions posed by therapists and documentarians, commanders and comrades to soldiers who are asleep or half asleep, or in the grip of sedatives or recurring memories so lifelike they seem real, reverberate through postwar representations of war trauma. Eventually, veterans, who had long served as objects of psychiatric investigation, became active opponents of war, using their analysis of wars emotional effects to pioneer new methods of war resistance. Claiming the right to query, discuss, and interpret their own traumatic symptoms, they adapted therapeutic concepts and practices and, in doing so, built on and radically redefined both military and mainstream psychiatry.