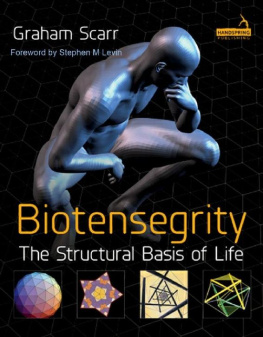

Biotensegrity

HANDSPRING PUBLISHING LIMITED

The Old Manse, Fountainhall,

Pencaitland, East Lothian

EH34 5EY, Scotland

Tel: +44 1875 341 859

Website: www.handspringpublishing.com

First published 2014 in the United Kingdom by Handspring Publishing

Copyright Handspring Publishers 2014

Photographs and drawings copyright Graham Scarr 2014 except for those indicated differently.

All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a license permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS.

The right of Graham Scarr to be identified as the Author of this text has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts 1988.

ISBN978-1-909141-21-6

eISBN 978-1-909141-47-6

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Notice

Neither the Publisher nor the Author assumes any responsibility for any loss or injury and/or damage to persons or property arising out of or relating to any use of the material contained in this book. It is the responsibility of the treating practitioner, relying on independent expertise and knowledge of the patient, to determine the best treatment and method of application for the patient.

Commissioning Editor Sarena Wolfaard

Design direction and cover design by Bruce Hogarth, kinesis-creative.com

Index by Dr Laurence Errington

Typeset by DiTech Process Solutions

Printed in the Czech Republic by Finidr Ltd.

The

Publishers

policy is to use

paper manufactured

from sustainable forests

Contents

Guide

T he concept of tensegrity as a structural design principle has been around since the middle of the twentieth century and is currently seeing a huge increase in interest. From early forays into a new form of sculpture it is now incorporated into architecture, the engineering of deployable structures in space, and is attracting the attention of biologists, clinicians and those interested in functional anatomy and movement.

Tensegrity models emulate biology in ways that were inconceivable in the past, but it has taken a while for the concept to become widely accepted because of its challenges to generally accepted wisdom (from which it has been dismissed as both too simple and too complicated), although this is perhaps understandable.

Anatomy and biomechanics have taken many centuries to accumulate a body of knowledge that is now unrivalled in any other sphere, but this progress has mostly been driven through advances in technology, and established conventions have allowed many inconsistencies to survive long past their sell by date. The relegation of fascial and other connective tissues to mere supportive roles; the tolerance of an incomplete lever system that loads destructive stresses on tissues that would be unable to withstand them; and the adherence to a Euclidean spatial system that compelled classical mechanics into taking a dominant role over biology, are significant examples; but things have moved on. These ideas were put forward at times when there was little serious alternative, and it is the associated imagery and scientific convention that have allowed them to persist into the present, but they have led biomechanics down a blind alley from which it is only just starting to recover.

As an orthopaedic surgeon in the 1970s, Stephen Levin observed things at the operating table that were at odds with conventional biomechanics theory, and he set out to find a more satisfactory explanation. Starting with the study of creatures that stretched these theories to the limit he discovered that tensegrity provided a more thorough assessment of biological mechanics at every size scale (Levin, 1981), and that it was also compatible with the natural laws of physics, eventually introducing the term biotensegrity to distinguish it from some engineering research that is not constrained by these rules in the same way. Around the same time, Donald Ingber, a cell biologist investigating the effect of physical forces on cancer cells also realised that tensegrity provided a better explanation of their changing behaviours (Ingber, 1981), and through experiment, detailed much of the cell mechanics and biochemistry that underlie cell function.

Both authors have considered biotensegrity in relation to the hierarchical organisation of living systems, from molecules to the entire body, and have written much on this subject over the past thirty years. Others have also made substantial contributions but it is only recently that a more widespread interest has been shown. Whilst much of this is due to the booming internet and new research that undermines traditional views of anatomy, clinicians are starting to recognise that biotensegrity provides a better explanation for the things that they observe in practice; and the intention of this book is to explain some of the basic principles of tensegrity and re-evaluate anatomy and biomechanics in the light of these findings.

The first chapter is an introduction to the tensegrity concept with a brief history of its development and some of the characteristics that make it important to structural biology. then look at how biotensegrity is transforming traditional views of anatomy and consider its implications to biomechanics, robotics and therapeutics. Just as every part of a tensegrity structure has an influence on every other part, it should be kept in mind that each section relies to some extent on all the others to be fully appreciated.

This book is not an instruction manual but a response to the frequently asked question, what is (bio)tensegrity; and it is hoped that it will inspire the reader to take a deeper look at biological structure and find their own ways of applying it. It is a personal perspective that recognises that all natural forms are the result of interactions between physical forces and the fundamental laws that regulate them, and that an appreciation of these simple precepts leads to a better understanding of the human body as a functionally integrated and hierarchical unit.

Graham Scarr

March 2014

I have friends and associates who have heard my Introducing Biotensegrity talk five, sometimes seven or eight times and still do not get it. Whether its my inability to communicate or the complexity of the topic, it usually takes some time to sink in. I presented a biotensegrity talk in the UK in 2004. Afterward, Graham Scarr came up to me and showed me a rather awkward, but remarkably well thought out, tensegrity model of an arm. We had previously corresponded by email, but I had no idea how capable he was and how much he had assimilated the biotensegrity concept. Our first conversation was brief and hampered by the fact that he speaks Midlands English, and I grew up in New York City and have a tin ear for languages. It was something right out of a Benny Hill sketch, but it was enough to let me know that this was a man I desperately needed on my side. Graham not only had grasped the concept on first go round, but had taken the ball and run with it. He has the background in science, the hands on skill and intuitive understanding of the body as an Osteopath, a deep interest in geometry, and the technical skill of a jeweler, a side hobby of his.