Kit Yates - The Maths of Life and Death

Here you can read online Kit Yates - The Maths of Life and Death full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Quercus Editions, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Maths of Life and Death

- Author:

- Publisher:Quercus Editions

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Maths of Life and Death: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Maths of Life and Death" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Maths of Life and Death — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Maths of Life and Death" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Maths of Life and Death

The Maths of Life and Death

Title

Kit Yates

The Maths of

Life and Death

Why Maths Is

(Almost) Everything

Quercus

Copyright

This ebook edition first in 2019 by

Quercus Editions Ltd Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK company

Copyright 2019 Kit Yates

The moral right of Kit Yates to

be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

HB ISBN 978 1 78747 542 7 TPB ISBN 978 1 78747 541 0 Ebook ISBN 978 1 78747 539 7

Certain names and identifying details have been changed

whether or not so noted in the text.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders.

However, the publishers will be glad to rectify in future

editions any inadvertent omissions brought to their attention.

Quercus Editions Ltd hereby exclude all liability to the extent

permitted by law for any errors or omissions in this book and for any loss,

damage or expense (whether direct or indirect) suffered by a

third party relying on any information contained in this book.

Cover design 2019 Andrew Smith

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

Dedication

For my parents,

Tim, Nancy and Mary,

who taught me how to read,

and my sister, Lucy,

who taught me how to write.

Contents

Introduction

Almost everything

My four-year-old son loves playing out in the garden. His favourite activity is digging up and inspecting creepy crawlies, especially snails. If he is patient enough, after the initial shock of being uprooted, they will emerge cautiously from the safety of their shells and start to glide over his little hands leaving viscid trails of mucus. Eventually, when he tires of them, he will discard them, somewhat callously, in the compost heap or on the woodpile behind the shed.

Late last September, after a particularly busy session in which he had unearthed and disposed of five or six large specimens, he came to me as I was sawing up wood for the fire and asked Daddy, how many snails is [ sic ] there in the garden? A deceptively simple question for which I had no good answer. It could have been 100 or it could have been 1000. To be quite honest, he would not have comprehended the difference. Nevertheless, his question piqued an interest in me. How could we figure this out together?

We decided to conduct an experiment. The next weekend, on Saturday morning, we went out to collect snails. After ten minutes, we had a total of 23 of the gastropods. I took a sharpie from my back pocket and proceeded to place a subtle cross on the back of each one. Once they were all marked up, we tipped up the bucket and released the snails back into the garden.

A week later we went back out for another round. This time, our ten-minute scavenge brought us just 18 snails. When we inspected them closely we found that three of them had the cross on their shells, while the other 15 were unblemished. This was all the information we needed to make the calculation.

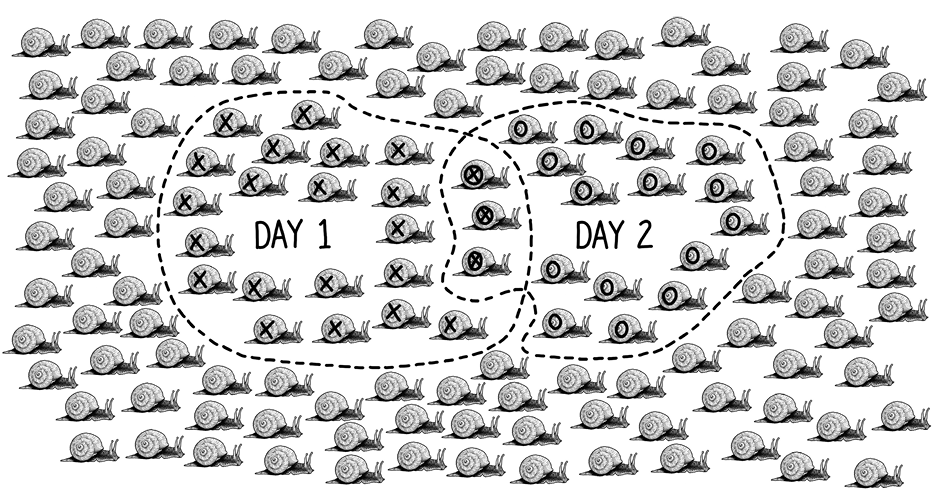

The idea is as follows: the number of snails we captured on the first day, 23, is a given proportion of the total population of the garden, which we want to get a handle on. If we can work out this proportion then we can scale up the number of snails we caught to find the total population of the garden. So we use a second sample (the one we took the following Saturday). The proportion of marked individuals in this sample, 3/18, should be representative of the proportion of marked individuals in the garden as a whole. When we simplify this proportion, we find that the marked snails make up one in every six individuals in the population at large (you can see this illustrated in Figure 1). Thus we scale up the number of marked individuals caught on the first day, 23, by a factor of 6 to find an estimate for the total number of snails in the garden, which is 138.

Figure 1: The ratio (3:18) of the number of snails recaptured (marked O X ) to the total number captured on the second day (marked O ) should be the same as the ratio (23:138) of the number captured on the first day (marked X ) to the total number of snails in the garden (marked and unmarked).

After finishing this mental calculation I turned to my son, who had been looking after the snails we had collected. What did he make of it when I told him that we had roughly 138 snails living in our garden? Daddy, he said, looking down at the fragments of shell still clinging to his fingers, I made it dead. Make that 137.

This simple mathematical method, known as capturerecapture, comes from ecology, where it is used to estimate animal population sizes. You can use the technique yourself, by taking two independent samples and comparing the overlap between them. Perhaps you want to estimate the number of raffle tickets that were sold at the local fair or to estimate the attendance at a football match using ticket stubs rather than having to do an arduous head count.

Capturerecapture is used in serious scientific projects as well. It can, for example, give vital information on the fluctuating numbers of an endangered species. By providing an estimate of the number of fish in a lake, This is the pragmatic power that simple mathematical ideas can wield. These are the sorts of concepts that we will explore throughout this book and that I use routinely in my day job as a mathematical biologist.

When I tell people I am a mathematical biologist, the reaction I get is usually a polite nodding of the head accompanied by an awkward silence, as if I was about to test them on their recall of the quadratic formula or Pythagoras theorem. More than simply being daunted, people struggle to understand how a subject like maths, which they perceive as being abstract, pure and ethereal, can have anything to do with a subject like biology, which is typically thought of as being practical, messy and pragmatic. This artificial dichotomy is often first encountered at school: if you liked science but you werent so hot on algebra, then you were pushed down the life sciences route. If, like me, you enjoyed science but you werent into cutting dead things up (I fainted once, at the start of a dissection class, when I walked into the lab to see a fish head sitting at my bench space) then you were guided towards the physical sciences. Never the twain shall meet.

This happened to me. I dropped biology at sixth-form and took A-levels in maths, further maths, physics and chemistry. When it came to university, I had to further streamline my subjects, and felt sad that I had to leave biology behind forever; a subject I thought had incredible power to change lives for the better. I was hugely excited about the opportunity to plunge myself into the world of mathematics, but I couldnt help worrying that I was taking on a subject that seemed to have very few practical applications. I couldnt have been more wrong.

Whilst I plodded through the pure maths we were taught at university, memorising the proof of the intermediate value theorem or the definition of a vector space, I lived for the applied maths courses. I listened to lecturers as they demonstrated the maths that engineers use to build bridges so that they dont resonate and collapse in the wind, or to design wings that ensure planes dont fall out of the sky. I learned the quantum mechanics that physicists use to understand the strange goings-on at subatomic scales and the theory of special relativity that explores the strange consequences of the invariance of the speed of light. I took courses explaining the ways in which we use mathematics in chemistry, in finance and in economics. I read about how we use mathematics in sport to enhance the performance of our top athletes and how we use mathematics in the movies to create computer-generated images of scenes that couldnt exist in reality. In short, I learned that mathematics can be used to describe almost everything.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Maths of Life and Death»

Look at similar books to The Maths of Life and Death. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Maths of Life and Death and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.