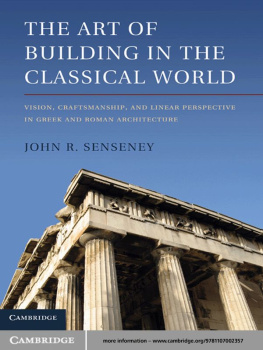

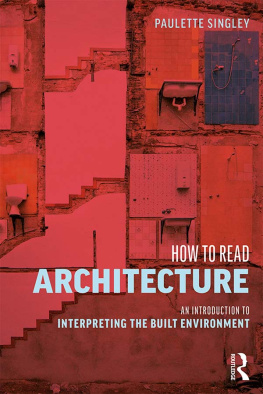

How to Read Architecture

How to Read Architecture is based on the fundamental premise that reading and interpreting architecture is something we already do, and that close observation matters. This book enhances this skill so that given an unfamiliar building, you will have the tools to understand it and to be inspired by it. Author Paulette Singley encourages you to misread, closely read, conventionally read, and unconventionally read architecture to stimulate your creative process.

This book explores three essential ways to help you understand architecture: reading a building from the outside-in, from the inside-out, and from the position of out-and-out, or formal, architecture. This book erodes boundaries between the frequently compartmentalized fields of interior design, landscape design, and building design with chapters exploring concepts of terroir, scenography, criticality, atmosphere, tectonics, inhabitation, type, form, and enclosure. Using examples and case studies that span a wide range of historical and global precedents, Singley addresses the complex interaction among the ways a building engages its context, addresses its performative exigencies, and operates as an autonomous aesthetic object.

Including over 300 images, this book is an essential read for both undergraduate and postgraduate students of architecture with a global focus on the interpretation of buildings in their context.

Paulette Singley is a widely read architectural historian and theorist whose work expands the disciplinary limits of architecture across diverse subject matter such as food, film, and fashion. She is a Professor of Architecture at Woodbury University in Los Angeles, California. She received a Ph.D. from Princeton University, an M.A. from Cornell University, and a B.Arch. from the University of Southern California. She co-edited Eating Architecture, the first book to explore the intersections of architecture and the culinary arts. She also co-edited Architecture: In Fashion and has published chapters in several anthologies as well as essays in architecture journals such as Log and Assemblage.

How to Read Architecture

An Introduction to Interpreting the Built Environment

PAULETTE SINGLEY

First published 2019

by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2019 Taylor & Francis

The right of Paulette Singley to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Singley, Paulette, 1960 author.

Title: How to read architecture : an introduction to interpreting the built environment / Paulette Singley.

Description: New York, NY : Routledge, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018061193| ISBN 9780415836180 (hardback) | ISBN 9780415836203 (paperback) | ISBN 9780429262388 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: ArchitectureAesthetics.

Classification: LCC NA2500 .S484 2019 | DDC 720/.47dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018061193

ISBN: 978-0-415-83618-0 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-26238-8 (ebk)

Typeset in Univers LT Std

by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire

Cover image: Photograph by Gerard Smulevich Barceloneta 2006 of an installation by the artist Marieke Polocsay (Marika) #Rehabilitacion

If not for you

David Hall and Connor Stankard

Given the scope and breadth of this work the number of individuals, particularly my colleagues, students and former professors, to whom I owe a debt of gratitude is innumerable. This book would not have been initiated were it not for the vision and support of Routledge and Taylor and Francis editors, particularly Krystal LaDuc, Julia Pollacco, Wendy Fuller, Kalliope Dalto, Nick Craggs, and Fran Ford. Copy-editor Jon Lloyd was intrepid. Cover designer Jo Griffin and indexer Angus Barclay also did a tremendous job. Woodbury University in general and Ingallil Wahlroos-Ritter in particular were highly supportive of this project at every juncture. I am grateful to the American University of Sharjah for an academic year in the middle east. I am particularly grateful to colleagues who spared time to read chapters: Jeffrey Balmer, Matthew Bell, Amy Converse, Deborah Fausch, Alicia Imperiale, Mark Jarzombek, Romolo Martemucci, John Montague, Pat Morton, Mikesch Muecke, Eric Olsen, Vikram Prakash, and Mark Stankard. Gavin Friehauf and Hitisha Kalolia completed careful diagrams and drawings. Thanks to Sean Dockray having initiated the knowledge-sharing platform of Aaaaarg, I was able to complete much of this work in remote locations. I should also mention the strategic interventions of Ron Evitts, Alessandra Ponte, David Rifkind, Georges Teyssot, Nick Roberts, Kazys Varnelis, and Astrid Virding. To David Hall, whose relentless image-finding breathed life into the visual arguments being made here, I am eternally indebted. There would be no book without his support and encouragement.

Paulette Singley

Altadena, California; Guildford, Connecticut; Rome,

Italy; Sharjah, United Arab Emirates;

Rocca di Caprileone, Sicily

Greek legend insists that Daedalus was the first architect, but this is hardly the case: although he built the Cretan labyrinth, he never understood its structure. He could only escape, in fact, by flying out of its vortex. Instead, it may be argued that Ariadne achieved the first work of architecture, since it was she who gave Theseus the ball of thread by means of which he found his way out of the labyrinth after having killed the Minotaur.

Beatriz Colomina

Imagine you are standing in front of a building you previously have not seen. Without the aid of a guide book or other supplemental information, but equipped with your native ability to reason and a basic knowledge of the culture with which you are engaging, how would you begin to interpret, that is to say read, this work of architecture? Perhaps you would examine the way the building engages its site, study the configuration of interior spaces as they evidence themselves on exterior surfaces, or compare it to similar precedents you remember having seen. If the building you are reading is an ancient ruin or prehistoric monument, then you might adopt the perspective of an archaeologist and seek to identify primary site alignments or mentally reconstruct the edifice from remaining wall fragments. The seemingly dumb stone blocks from which a building was constructed may carry information that communicates architectural knowledgethe proximity of the quarry to the building site, chisel marks remaining from the extraction process, and more. To study an extant structure instead of a ruin, one might survey the ways in which the building responds to the nature of the site or consider its familial parallels to adjacent buildings. These techniques of observation, combined with an understanding of larger cultural forces such as socio-religious practices, contribute to an

![Architecture for Humanity - Design like you give a damn [2] building change from the ground up](/uploads/posts/book/178090/thumbs/architecture-for-humanity-design-like-you-give-a.jpg)