Barnard Mary E. - Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain

Here you can read online Barnard Mary E. - Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: University of Toronto Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Toronto Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

OBJECTS OF CULTURE IN THE LITERATURE OF IMPERIAL SPAIN

EDITED BY MARY E. BARNARD

AND FREDERICK A. DE ARMAS

University of Toronto Press 2013

Toronto Buffalo London

www.utppublishing.com

Printed in Canada

ISBN 978-1-4426-4512-7

Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Objects of culture in the literature of imperial Spain / edited by Mary E. Barnard and Frederick A. de Armas.

(Toronto Iberic)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4426-4512-7

1. Spanish literature Classical period, 15001700 History and criticism. 2. Material culture in literature. 3. Material culture Spain History. I. Barnard, Mary E., 1944 II. De Armas, Frederick A. III. Series:

Toronto Iberic.

PQ6064.O25 2013 860.9'3550903 C2012-907216-8

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing activities.

MARY E. BARNARD

MARSHA S. COLLINS

FREDERICK A. DE ARMAS

MARA CRISTINA QUINTERO

CHRISTOPHER B. WEIMER

HEATHER ALLEN

EMILIE L. BERGMANN

EDWARD H. FRIEDMAN

ROBERT TER HORST

CAROLYN A. NADEAU

RYAN D. GILES

LUIS F. AVILS

TIMOTHY AMBROSE

GORETTI GONZLEZ

Chapter 1

.

.

.

.

Chapter 3

.

.

.

.

.

Chapter 11

.

Chapter 13

This collection is about objects that are described or alluded to in books, objects like clothing, paintings, tapestries, playing cards, enchanted heads, materials of war, monuments, and books themselves. The notion of objects within books, and of books within objects, had a lasting currency. According to ancient texts, Alexander hid the Homeric Iliad under his pillow, wanting to emulate the feats of Achilles and Ulysses. Legend has it that when he found a luxurious chest among the booty taken from King Darius, he ordered the Iliad to be placed within it. This second tale became so popular in the Renaissance that a grisaille painting, Alexander the Great Places Homers Iliad in Safe Keeping, appears in Raphaels Stanza della Segnatura at the Vatican (Jones and Penny 1983, 74). The painting, which allows us to view the moment in which the book was placed in a magnificent coffer, was, in turn, the subject of an engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi, the famous popularizer of Raphael during the Renaissance (Shoemaker and Brown 1981, 10). These two objects, book and coffer, continued to live through painted and engraved images as well as in written texts such as Cervantes Don Quixote (de Armas 2007, 27). Like the Iliad, the objects discussed in Objects of Culture pass through many hands, being valorized, hidden, collected, and exhibited for a variety of reasons. The journeys of these textual objects can tell us much as to what was valued and what was shunned, what held power and what subverted it in imperial Spain.

The production of goods in all forms permeated the cultural life of early modern Europe (Jardine 1996). Collecting and displaying finely crafted objects was a mark of character and taste, and a sign of magnificence. Indeed, the ceremonial show of material treasures ranked with extravagant hospitality as a hallmark of noble virtue and as a token of princely power and status (Swann 2001, 16). The monarchs of imperial Spain shared that disposition, and became dedicated collectors. The itinerant court of Charles V (r. 151656) carried in its train sets of tapestries for public display during his travels, while his Titians performed a similar service in his palaces, an ostentatious self-marketing learned from his grandfather Maximilian (Silver 2008). Philip II (r. 155698) amassed a collection of relics that revealed the pious side of his character (Lazure 2007), all the while keeping a private collection of erotica hidden behind curtains at the Pardo, consisting notably of several Titians, including a Venus and a Dana. Philip III (r. 15981621) likewise was an energetic collector of paintings of the premier artists of his day and of other luxurious objects that comprised one of the largest collections of its kind (Schroth, Baer, et al. 2008). His valido the Duke of Lerma (160336), chief architect and procurer of works of art, amassed a huge personal collection of tapestries, jewellery, reliquaries, and foreign and domestic glass and ceramics. Thirteen recently discovered household inventories list his enormous private collection, numbering between 1500 and 2747 paintings, which hung in his various residences (Schroth, Baer, et al. 2008, 88). Lerma stood as a mirror of royal tastes and aspirations in acquiring and gifting cultural objects. It is a tribute to his ambitions that he commissioned a palace larger and more magnificent than the Escorial, and more suitable to display his unrivalled collections of art and artefacts. But Philip III was not to be challenged on that score, and the duke fell from royal favour. Only kings and emperors could play the game of cultural superiority against each other.

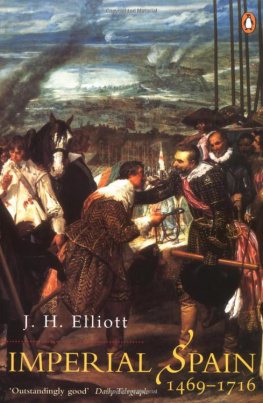

Philip IV (r. 162165) is well known for favouring the paintings of Rubens, Poussin, and especially his court painter, Diego Velzquez. Indeed, it is said that the visit of Charles, Prince of Wales, to Madrid in a quixotic knight errant effort to woo the infanta Mara was the culminating experience in his education as a collector, as a junta was organized to guide Charles and his entourage through local collections (Brown 1995, 33, 35). Instead of a promise of marriage, the prince left for England with a treasure trove of art works, the most important being gifts from the king: Titians Pardo Venus and Charles V with a Hound as well as Veroneses Mars and Venus (Brown 1995, 37). But Philip did not surrender his favourite paintings, and he soon acquired many more, especially by Velzquez, whose Surrender of Breda (16345) held a privileged place in the Hall of Realms of the Buen Retiro, the pleasure palace built by Philip IV in the 1630s on the outskirts of Madrid.

Like the palaces and collections of the Duke of Lerma, the Buen Retiro served as a prism through which to view the royal court and, more generally, the cultural and political doings of imperial Spain. In their classic study, A Palace for a King (2003), Jonathan Brown and J.H. Elliott sought to recapture the material and cultural life of the Buen Retiro. Through a comprehensive study of the great central hall, the Hall of Realms, and its paintings, which are the only objects to survive from the complex of palace buildings and grounds, Brown and Elliott recovered a rich court life saturated with objects, mostly paintings, prints, tapestries, sculpture, furniture, and the related trappings of a powerful monarch. With the Buen Retiro serving as the architectural frame for the objects commissioned, collected, and displayed within it, the royal court can now be understood as a complex melding of place, events, and objects with which it was identified. No less grand than Fontainebleau, Versailles, or the Pitti, the Buen Retiro and other stately houses and palaces of the Habsburg kings of Spain the Escorial, the Alcazar of Madrid, the Pardo were well appointed to guard the cultural objects acquired by the royals, with court theatre and political intrigue vying for attention with patronage and collecting. The monarchs of imperial Spain, from Charles V through Philip IV, surrounded themselves and their courts with cultural objects in a manner unimaginable by their predecessors, and their collections, both for public display and for private contemplation, rivalled or surpassed those of other European monarchs of the time.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain»

Look at similar books to Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.