Brilliant... Dyer's eyes miss nothing Peter Conrad, Observer

It was wildly ambitious to try and turn this galaxy of theory into a readable work of scholarship but Byrne has done it, and done it with style Mark Ellen, Observer

Both wonderful and necessary Anne Enright, Guardian

Also by Jules Evans

Philosophy for Life: And Other Dangerous Situations

Published in Great Britain in 2017 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street,

Edinburgh EH1 1TE

www.canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2017 by Canongate Books

Copyright Jules Evans, 2017

Extract from Four Quartets reprinted by kind permission of Faber & Faber Ltd

(Faber & Faber, 2001) T.S. Eliot (1944); Valerie Eliot (1979).

Extract from Anthem, Stranger Music reprinted by permission of Penguin Random

House Canada Limited Leonard Cohen, Stranger Music (1993).

Extract from The Guest House, Rumi: Selected Poems reprinted by permission of

Penguin Random House Rumi/Coleman Barks (2004).

The moral right of the author has been asserted

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any further editions.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78211 867 1

eISBN 978 1 78211 877 0

Typeset in Bembo by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd,

Falkirk, Stirlingshire

To my brother, Alex,

and to Frederic Myers and Thomas Traherne,

two English ecstatics who deserve still to be in print.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Paleo-anthropologists think cave paintings like these at Lascaux (from around 20,000 BC) were an early route for homo sapiens to reach altered states of consciousness.

Sisse Brimberg/National Geographic

Ecstasy also had a central role in classical culture this vase painting (right) shows a maenad filled with the god Dionysus.

The Trustees of the British Museum

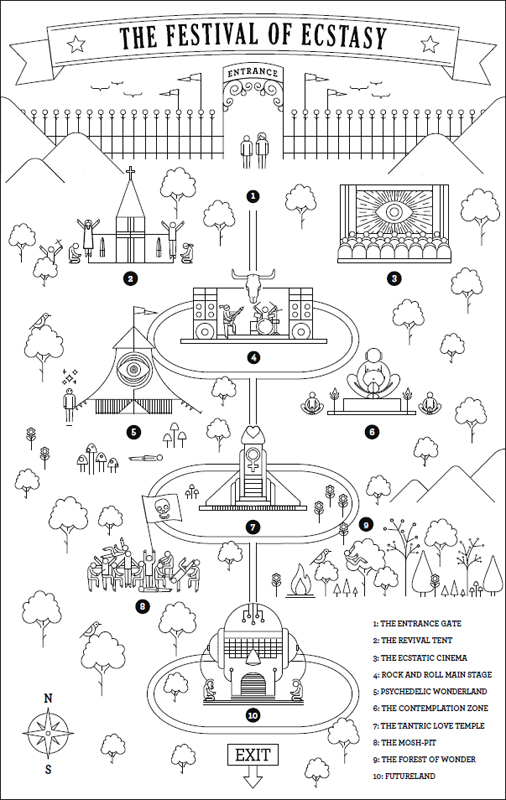

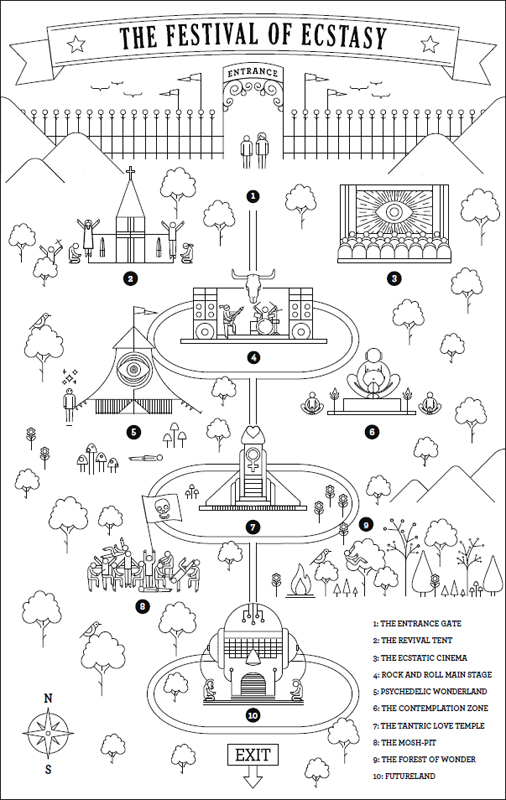

Introduction: Welcome to the Festival

I was walking along the beach beside Bamburgh Castle in Northumberland. It was a clear, bright September afternoon on one of the most beautiful stretches of coast in England. Across the water was Holy Island, where St Cuthbert had worshipped standing in the sea, and his followers had created the Lindisfarne gospels, the oldest and perhaps most beautiful book in European culture.

But I wasnt thinking about any of that. I was trying to get an internet connection. I was expecting an important email. I checked my phone again. Still nothing. I was in a tetchy mood. Id come up there for a peaceful getaway from London, but was disturbed until the early hours by a wedding party in the hotel bar, then awakened at six by sea-gulls cackling at me from the street outside. Bloody sea-gulls. Bloody wedding party. Bloody internet. Bloody beach.

And then something changed. I started to enjoy the walk, the exertion, the feel of the wind on my face, the give of the damp sand under my boots. The rhythm of walking calmed my mind. The waves washed in, nibbled at my boots, and washed out again. A Labrador ran up and wagged hello. I looked up and noticed quite how huge the sky was. It was streaked with thin white wisps, like marble, lit up by the sun setting behind the castle, and the light was reflected in the water on the sand.

It was as if the world was exploding with fiery intelligence. It filled me with an almost painful sense of its beauty. Yet this was just one moment in one corner of Earth, more or less unnoticed, except by the handful of people walking along the beach. My heart lifted with gratitude for this planet of endless free gifts.

I set off for my hotel in a completely different mood. I felt lifted beyond the narrow anxiousness of my ordinary ego, switched into a more open, appreciative and peaceful mindset. I thought about taking a photo of the sunset and sharing it on Facebook. And then I thought, No, theres no need to go begging for others likes. Just enjoy the moment without trying to convert it into social capital. But, obviously, I did take a photo, and I did post it on Facebook. It got ninety-one likes!

Our basic need for transcendence

In some ways, that moment was quite ordinary. It was just one of those moments that come along now and then, when our consciousness expands beyond its usual self-obsessed anxiousness into a more peaceful, absorbed and transcendent state of mind. It can happen when were sitting on a bus, playing with our children, reading a book, walking in the park. Something catches our attention, we become rapt, our breath deepens, and life quietly shifts from a burden to a wonder. These are the little moments when we expand beyond the ego, and theyre deeply regenerative.

The writer Aldous Huxley argued that all humans have a deep-seated urge to self-transcendence. He wrote: Always and everywhere, human beings have felt the radical inadequacy of their personal existence, the misery of being their insulated selves and not something else, something wider, something in Wordsworthian phrase far more deeply infused.

The philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch called it unselfing. She wrote: We are anxiety-ridden animals. Our minds are continually active, fabricating an anxious, usually self-preoccupied, often falsifying veil which partially conceals our world. But this anxious ego-consciousness can shift through focused attention, particularly when were absorbed by something beautiful, like a painting or a landscape. Murdoch continued: I am looking out of my window in an anxious and resentful state of mind, oblivious of my surroundings, brooding perhaps on some damage done to my prestige. Then suddenly I observe a hovering kestrel. In a moment everything is altered. The brooding self with its hurt vanity has disappeared. There is nothing now but kestrel.

All of us need to find ways to unself. Civilisation makes great demands of us: we must control our bodies, inhibit our impulses, manage our emotions, prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet. We must play our role in the great complex web of globalised capitalism. Our egos have evolved to help us survive and compete, and they do a good job at this, by spending every second of the day scanning the horizon for opportunities and threats, like a watchman on Bamburgh Castle looking out for Vikings. But the self we construct is an exhausting place to be stuck all the time. Its isolated, cut off by walls of fear and shame, besieged by worries and ambitions, and conscious of its own smallness and impending mortality. Thats why we need to let go, every now and then, or we get bored, exhausted and depressed.