Copyright 2017 by Justin Davidson

Maps copyright 2017 by David Lindroth Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

S PIEGEL & G RAU and Design is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Portions of this work were originally published in New York magazine and its associated websites, Vulture and Daily Intelligencer. An earlier version of the Introduction was originally published in Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao: New York (Aperture, 2014). A short section of Walk I: City of Money was adapted from an article originally published in Newsday.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

NAMES : Davidson, Justin.

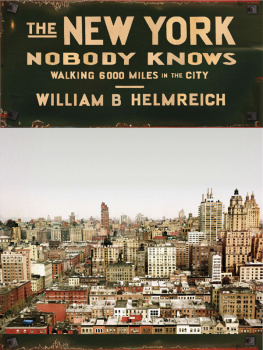

TITLE : Magnetic city : a walking companion to New York / by Justin Davidson.

DESCRIPTION : New York : Spiegel & Grau, [2017] | A Spiegel & Grau trade paperback originalTitle page verso. | Includes index.

IDENTIFIERS : LCCN 2016041362 | ISBN 9780553394702 (paperback : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780553394719 (ebook).

SUBJECTS : LCSH: New York (N.Y.)Description and travel. | WalkingNew York (State)New York. | New York (N.Y.)History. | Historic buildingsNew York (State)New York. | Historic sitesNew York (State)New York. ArchitectureNew York (State)New York. | New York (N.Y.)Buildings, structures, etc. | BISAC: TRAVEL / Hikes & Walks. | ARCHITECTURE / Regional. | HISTORY / United States / State & Local / Middle Atlantic (DC, DE, MD, NJ, NY, PA).

CLASSIFICATION : LCC F128.55 .D38 2017 | DDC 974.7dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016041362.

Ebook ISBN9780553394719

randomhousebooks.com

spiegelandgrau.com

Cover design: Evan Gaffney

Cover photograph: Stephen Wilkes / Gallery Stock

v4.1

ep

Contents

The soul of the city was always my subject, and it was a roiling soul, twisting and turning over on itself, forming and re-forming, gathering into itself and opening out again like blown cloud.

E. L. D OCTOROW , from The Waterworks

If you had fled New York when the World Trade Center site was still a pile of smoldering rubble and first returned when a new one was needling the sky, you would have found that the city had changed its skin. During the dozen years from 2002 until the end of 2013, when the peoples plutocrat, Michael Bloomberg, was mayor, a metropolis famed for its lively grubbiness acquired a fresh glow. Graffiti migrated to other cities or was confined to designated zones like the 5Pointz development in Long Island City. Central Parks lawns were lacquered in pool-table green. The once-pervasive fug of cigarette smoke cleared, replaced by pollen clouds from hundreds of thousands of new trees. (Respiration remains a problem but only at certain times of year.) Every time an old stone building fell, its rusticated quoins, wrought-iron curlicues, and carved brownstone lintels were replaced by the uniform smoothness of glass. At dusk, mauve sunlight ricocheted off the Hudson River and inflamed all those mirrored faades. Suddenly, New York looked cleaner, lighter, and shinier: a city that could be made new again each morning with the stroke of a squeegee.

Some of that newness was deceptive. The shiny-skinned metropolis was draped over a century-old subway and a sclerotic circulation system of rusty water pipes and fragile gas mains. Periodically, a building crumbled or a rainstorm crippled the sewers, reminding all New Yorkers that they lived in a city of a certain age. But the seductive sheen had a substance to it, too, like the many coats of high-gloss paint that build up on a prewar kitchens walls. Crime fell, crack crested, and the worst of the drug scourge migrated to previously wholesome places like Vermont. Overt racial conflict abated, and middle-class couples were emboldened to stay rather than make a run for the suburbs as soon as they bought their first bassinet.

New York reasserted itself as a magnetic city, drawing all kinds of people for all different reasons, from all over the world. The preposterously rich came shopping for ninetieth-floor estates that they left vacant virtually year-round. Their extravagant demands (combined with new technology, the scarcity of land, and the open-ended premium that developers could charge for views) inspired an architectural form that was new to New York: the anorexic-supermodel tower, hyper-tall and spectacularly skinny. The less pampered came, too. Indigent immigrants, freshly laureled college grads, nurses, retirees, writers, and middle-aged refugees from the ranch-house lifeeveryone needed a portion of that precious resource, square footage. The tide brought companies as well as individuals. The cream of Silicon Valley, like Google, Facebook, and Twitter, discovered their need for a Manhattan beachhead. Financial firms that had dispersed to New Jersey office parks found themselves slinking back into town. TV producers renewed their love of New York so passionately that they pressed Midtown into service as a fake Chicago for The Good Wife and made the Brooklyn neighborhood of Ditmas Park impersonate Iowa CityIowa City!in Girls. Then there were the tourists, millions upon millions of them, ambling too slowly and four abreast, infuriating the localsbut also buoying cultural institutions and broadcasting New Yorks status as a global object of desire. New Yorkers could count on being envied.

The gloss and the frenzy represented real change, much of it for the better, some of it disastrous, none of it forgone. Years after 9/11, New Yorkers continue to live with the events afterimage engraved in our prefrontal cortex. But we have forgotten the ensuing gloomthe worries that nobody would ever again want to live or work in a skyscraper, that Manhattan was doomed as a financial capital, that those who could flee would, and that those who had already fled would never return. Despair and resilience are recurring motifs in the history of a city that has regularly been battered, doubted, cursed, and loathed, only to battle its way back to glamour. In 1835 a fire destroyed virtually the entire business district; within a few years, a stronger, less flammable city emerged. At the end of World War II, New York had the worlds busiest port and most productive factories. Three decades later, shipping and manufacturing were both moribund, the municipal government could barely pay its bills, and the East Village teemed with punk rockers nihilistic screams.

But another quarter century later, New Yorkers discovered that while they were hard at work againnow mostly in offices rather than on factory floorsthey also inhabited a city optimized for leisure. A greenbelt of parks curled along once-begrimed docks, studded with sunbathers from May to September. Fun, it turned out, feels better when it takes place near water, and now the citys five hundred miles of shoreline were lined with places to drink, skateboard, play