1. Theories of Facial Aging: Gravitational Versus Volumetric

The aging of the facial region is a continuous, dynamic process in which different tissues are involved. The phenotype of an aging face is not just the product of isolated changes in different tissue planes revealed by anatomic and radiologic studies such as bone remodeling, tissue descent secondary to gravity, attenuation of the retaining facial ligaments, atrophy of fat compartments, and structural and functional impairments in different layers of the skin; it is also the result of the interaction among all these factors.

Precisely because facial aging is caused by a combination of causes and mechanisms of action on a very wide range of tissues in which modifications at one plane affect all the others, there is no one isolated theory that can provide a clinical understanding of its development. Probably the best way to understand it is to link together the different theories that have been put forward to explain these changes.

In this chapter we will not assess the changes at the molecular or cellular level [], which clearly have a role to play in the physiologic and functional deterioration of the different structures. Rather, we focus on the main theories which, from a clinical point of view, help to explain the development of the aged face over time and the suitability of each surgical technique in specific cases.

Over the years many theories have been put forward to try to explain facial aging from a clinical perspective. Broadly speaking, they can be summarized under two headings: the gravitational theory and the volumetric theory, which include the model of pseudoptosis.

The gravitational theory emerged during the 1990s, after the description by Furnas [] of osseocutaneous and musculocutaneous fibrous condensations that help to stabilize and support the different structures of the facial region. This theory identifies the increased laxity of the facial retaining ligaments and the loss of their ability to support facial soft tissue as the main cause of the faces vertical descent, including excessive sagging and the appearance of folds or creases.

Authors like Stuzin et al. [] studied these multilinked fibrous ligaments and the facial spaces in depth. They posited that continuous muscle activity causing the stretching of the facial ligaments, together with the intrinsic changes typical of aging, is probably responsible for the weakness and elongation of this ligamentous support, leading to subsequent tissue ptosis.

In accordance with this gravitational theory, lifting techniques were introduced involving a wide dissection of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) [].

The gravitational theory was generally accepted until the early 2000s, when observational studies [] began to identify differences in behavior between different facial regions. It was proposed that the changes in the facial region may not be caused only by a vertical descent and ptosis of the tissues but also by a redistribution of volumes between the soft tissue and facial skeleton of the different subunits of the face.

Indeed, analyzing volumetric changes in the aging midface using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging, Gosain et al. [], in a comparison of photographs of 83 patients at different stages in their lives, noted that the vast majority of skin landmarks in the periorbital and midface and the lid-cheek position did not descend over time. This author hypothesized that the vertical descent of the skin and subcutaneous tissue was not a major component of the midfacial aging process; if the face actually sagged, one would expect to see downward migration of skin landmarks.

For many years, facial fat was considered a confluent mass divided into a superficial plane and a deep plane in relation to the SMAS and the muscles of facial expression. Later, Macchi et al. [] observed an inferior migration of the midfacial fat compartments and an inferior volume shift within the compartments during aging, concluding that distinct compartment-specific changes contribute to the aged appearance of the face.

In parallel to this understanding of the redistribution of volumes in the different fat compartments of the facial region with aging, some radiologic studies also showed a resorption and recession in specific locations in the facial skeleton [. As in the case of the atrophy of the deep fat compartments, these changes in the facial skeleton not only lead to a selective loss of projection in specific areas but reduce the support for the more superficial soft tissue and fat compartments and cause a certain degree of remodeling. In addition, bone recession may alter the position of the attachments of facial muscles and ligaments through the periosteum, which presents a slight backward displacement.

This loss of support caused by volumetric changes in deep structures has given rise to the model of pseudoptosis [] inside the volumetric theory. This model is the result of the clinical observation that restoring and giving volume in the deep compartments of the malar region not only corrects the negative vector (the projection of the malar region that remains in front of the corneal surface when seen in profile) but also improves other areas such as the nasolabial folds.

The theory of pseudoptosis suggests that selective deflation of the deep fat pads with age leads to a loss of support and the descent of the overlying superficial fat, thereby contributing to the ptotic appearance of the aging face.

The effect is like that created by inflating or deflating a balloon. When full of volume, the superficial compartments located between the deep compartments and the skin remain in position. When the deep compartments lose volume, the support is lost, and the superficial compartments are no longer impacted on the dermis; when this volume is lost, the tissue manifests ptosis.

The evolution of these two theories of facial aging, the gravitational and volumetric, shows why there is a need not only to correct sagging in the peripheral areas of the face and neck using facelift techniques but also to reverse the atrophy and redistribute volume in the central regions of the facewhich, after all, are the most visible areas [].

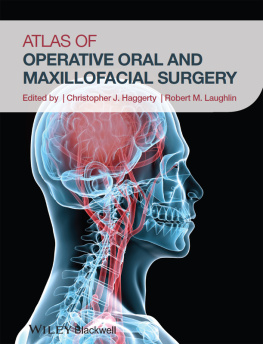

Therefore, to obtain the most natural-looking results possible, it is necessary to use techniques that rejuvenate both the peripheral and the central areas of the face, complementing conventional approaches with procedures to provide volume at the points where it has been lost. Our aim is to reconstruct a rejuvenated facial contour, not just to correct excess skin laxity (Fig. ).

Fig. 1.1

Face and neck rejuvenation techniques need to correct sagging in the peripheral areas of the face using facelift techniques ( red ) but also to reverse the atrophy and redistribute volume in the central regions of the face ( green )

References

Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Molecular mechanisms of skin aging: state of the art. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1119:4050. CrossRef PubMed