Table of Contents

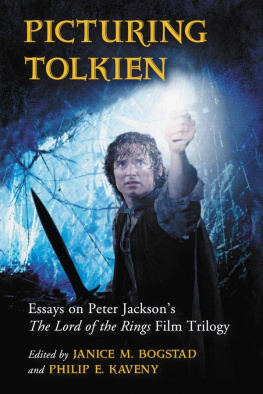

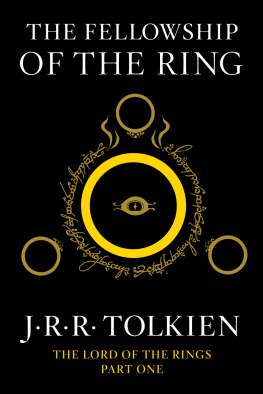

Picturing Tolkien

Essays on Peter Jacksons

The Lord of the Rings

Film Trilogy

Edited by

JANICE M. BOGSTAD and

PHILIP E. KAVENY

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Picturing Tolkien : essays on Peter Jacksons The Lord of the Rings film trilogy / edited by Janice M. Bogstad and Philip E. Kaveny.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7864-4636-0

1.Lord of the rings films History and criticism.2.Jackson, Peter, 1961Criticism and interpretation.3.Tolkien, J.R.R. (John Ronald Reuel), 18921973Film adaptations.I. Bogstad, Janice M., 1950II.Kaveny, Philip E.

PN1995.9.L58P53 2011

791.43'75dc23 2011021595

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

2011 Janice M. Bogstad and Philip E. Kaveny. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover image: Elijah Wood as Frodo in the 2003 film The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (New Line Cinema/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

In memory of Dr. Fannie J. LeMoine,

Professor of Classics and Comparative Literature

at University of WisconsinMadison,

a respected and much-loved mentor and friend to Tolkien scholars herein

an Elvish-spirit taken away far too soon

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the University of WisconsinEau Claire and University of Wisconsin System, which provided Dr. Janice Bogstad with the sabbatical that allowed her time to initiate this project and allowed both Philip Kaveny and her access to library and computing resources, including the skilled assistance of the LTS staff at Eau Claire, especially Beth Krantz, for negotiating some of the more arcane aspects of Word. Thanks also for the patience of various staff at the McIntyre Library who listened, commiserated and thus contributed to the completion of the project. Credit is also due to Catherine Currier, Josh Lang, Hank Luttrell, and Richard C. West for their various editorial efforts. The kind consultations of Douglas Anderson and Robert Woosnam-Savage, the latter of whose telephone calls and encouragements were a welcome interruption on many grim and dull days in the winter of 2009 and the spring of 2010, were much appreciated. Thanks to Robert E McKiernan, Jr., for the gift of his insights and friendship. Finally, the ongoing cooperation of authors found in this work was much appreciated by Janice and Philip in their first attempt to edit a collection of this type. It has been an often exciting, sometimes exhausting, generally educational, and ultimately very satisfying journey from conception to execution (we liked to watch the making of film where Jackson talks about the final days of filming pickups for inspiration).

Preface

JANICE M. BOGSTAD and

PHILIP E. KAVENY

More than a decade has passed since the beginning of cinematic production on The Lord of the Rings (hereafter LOTR) films in Wellington, New Zealand. Yet the websites persist, fan and scholarly commentary continues and so does the general fascination for the fate of its prequel, The Hobbit, as negotiations continue with directors and rights management people. Thus our little book has a place, between two periods in the controversy over cinematic renderings of J.R.R. Tolkiens The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings (hereafter Lord), novels near and dear to the American Baby Boomer generation and to most of the rest of the world. We had at first anticipated difficulties in finding contributors, but we quickly discovered that a lot of people in a lot of different critical circles still have a lot to say.

It has been a singular pleasure to work with the varied group of authors finally selected for our essay collection. The homogeneity sometimes found in collections of this kind may not be immediately apparent because our essayists come from many different critical traditions. For example, we have film critics, critics of folklore and Tolkien fandom, literary critics and a weapons specialist among our group. We have essayists who have published entire books on Tolkien and entire books on subjects such as the history of cinema as well as those who have not yet published on Tolkien. Yet the essays intersect, contrast, converge and diverge in significant and telling ways. So, for example, where Drout presents the noncontiguous relationship between the culture of Tolkiens Rohirrim and historical Anglo-Saxon culture, an area of expertise for both him and Tolkien, Savage references Anglo-Saxon arms and armor as only one of the many sources for weapons created in the film.

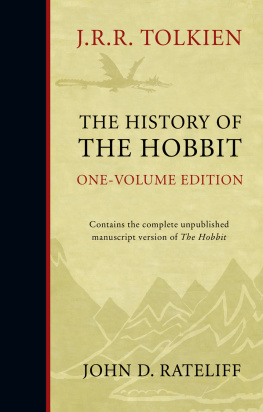

Also, the tendentious issue of written narrative versus cinematic narrative emerges in at least a third of the essays, both around the strength of language over the visual in its evocative powers (Flieger, Ricke and Barnett, and Rateliff) and the uniqueness of the cinematic in conveying such experiences as a visceral connection to characters (Walter). Some, such as Croft, Kaveny, and West, have chosen to focus on character and others on background, such as the physical and cultural setting of the Rohirrim (Drout), the Elves and Lothlrien (Ricke and Barnett) and arms and armor of Elves, Men, Hobbits, Dwarves, Uruk-hai and Orcs (Woosnam-Savage) or the potential reality of the West (Ford and Reid). It is especially exciting to see how similar cinematic gestures have been interpreted differently, for example in the controversial absence of all reference to Tom Bombadil and chiefly to the Scouring of the Shire in the films. While some, like Flieger, criticize this absence as oversimplifying the story, others, such as Rateliff and Thompson, elucidate cinematic reasons for its absence. Several authors acknowledge that, to most fans of Tolkien, the Jackson films are another road to Middle-earth. And this group includes literary as well as film critics.

What should emerge in considering all the essays is that the films have a large, enthusiastic audience and that there is a significant overlap between those who love the films and those who love (and have for a very long time in some cases) the books. Many enthusiasts and scholars relate that Tolkien got them interested in the study of languages, in alternative history, in medieval studies or one of its many branches, such as Anglo-Saxon studies, and that Tolkien has inhabited at least a corner, if not a significant portion, of their lives. That is of course the reason that the Tolkien films will be influential for a long time to come: they draw yet another group of people, those who might not otherwise have been visitors to Middle-earth, into this complex and, yes, liminal realm which the rest of us have cherished. For many book-firsters, Middle-earth was more like an alternative reality than an escape fantasy. It influenced the careers we chose and helped us chart our niche in the complex world of the present. And these many are not all Anglo-American or even European. Scholars of Tolkien can attest to the many languages in which translations of the books and now the films are being experienced by readers young and not so young. When we mention Tolkien to our Chinese friends, old and young alike, they attest to having read the novels or seen the films, most often both. And the books offer such richnessof knowledge, of the spiritual, of literary sophistication, of the nature of history and historical culturesby giving examples of how they can be built in a literary form. While we dont agree with all the conclusions in these essays, we agree with their core of understanding, that exposure to Tolkien and the many sub-creations he spawned are akin to what Dewey and others of his time called a public good. And according to many represented in this collection, Jacksons efforts cannot diminish Tolkiens accomplishments, they can only deepen them.