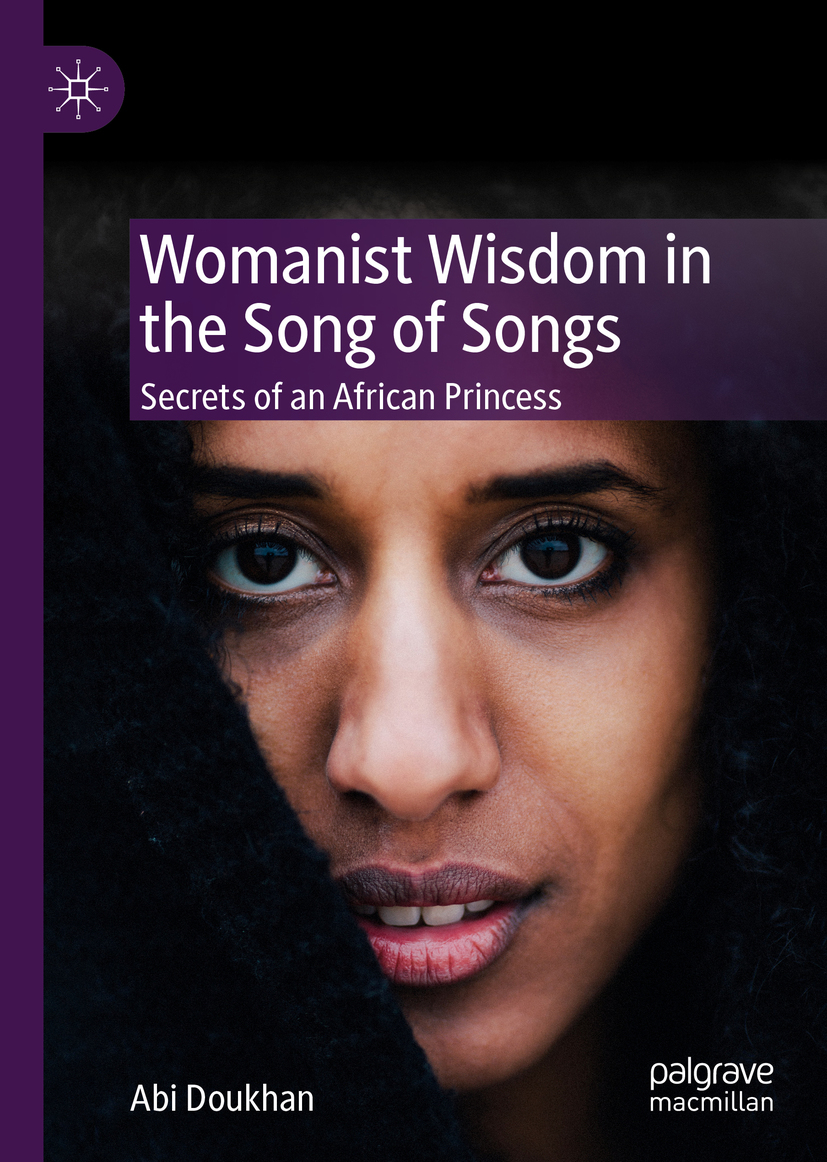

The Shulamite: Feminist or Womanist?

The Song of Songs teachings on love have been quoted for centuries to women and men alike in order to extoll the virtues and blessings of marriage . It has been a reference book for couples and for singles alike looking for love. Its oft quoted do not arouse or awaken love before it so desires has been used to dissuade young lovers from the reckless passions of their youth and the Shulamite has been set up as an example of virtue . Yet, though the Song has been understood by Christian and Jewish traditions alike as a celebration of virtuous love, I do not believe that the Song of Songs was intended for a virtuous audience, let alone an audience of virtuous women. On the contrary, I would argue that the Song was written for those women who, like its central character the Shulamite, have had the audacity to err, have wandered off the derech and have dared venture outside of the protective limits of patriarchy . It is intended for those women whose hearts have led them to transgress and who have been lured away from the roads well-traveled by the exigencies of love. The Song of Songs was composed for those women who, like its feminine protagonist, have let love entice them from the safety of the walls of Jerusalem to the wild and untamed vineyards and blossoming fields of Galilee. And it is for those women who have found themselves often with more questions than answers as to how to navigate the new territory that love has led them to; for those women who with their new-found freedom at times still find themselves confused, vulnerable and hurt by love in a post-patriarchal world. For to leave behind patriarchy is also to leave behind its protective structure, clear rules of engagement and comforting rhythms. Within patriarchy , the dance of love is already scripted and each partner knows what to do and what not to do. Everything is set up to ensure minimal damage to the hearts of both parties. To choose to leave behind patriarchy is therefore to expose oneself to certain risk and certain confusion as to how to navigate the untamed and dangerous waters of love. But can the heart even thrive in such a lawless dimension? Can the labor of love take place in a space of transgression ? Does an alternative wisdom exist apart from the wisdom of the ancients? In other words, is it still possible to find lasting love when one has erred, sinned or become damaged goods ? When one has dared venture outside of the walls of Jerusalem?

The good news is that our Shulamite has herself wandered off the derech. She is herself damaged goods having lost her virginity , thereby shaming her brothers . She has herself ventured outside of the protective walls of patriarchy in her approach to love and brazenly continues to do so with her present lover in the Song. She has broken every rule of engagement and courtship as well as the more implicit and delicate laws of modesty and discretion . And yet, she finds lasting love. This chapter explores her secret, her wisdom and her path as well as the grace that she encounters along the way. Our Shulamite has rejected the wisdom of the ancients, but, in the tumultuous throes of her love, she begins to craft her own wisdom; she has left behind the protection of patriarchy , but awakened to her own inner strength and courage. Ultimately it is not only love that she finds but herself. And though her path is often hard and her lover difficult, her willingness to submit to the love she finds herself in leads to her transformation and blossoming into a beautiful, strong and wise woman . The Song is ultimately a poem on a womans initiatory journey to love. It is the feminine companion to the heros journey sung by Greek epic writers such as Homer. Here we have a no less heroic journey but the protagonist is a woman and her destination is the wild and uncharted territory of love. In the process, however, she finds much more than a companion; she finds herself. Our Shulamites journey to herself, to her womanhood, her wisdom and her strength, is thus indissociable from her encounter with her lover.

Yet, although our Song unravels the experience of a woman having rejected the structures of patriarchy , our protagonist is no feminist Yet, patriarchal culture has, more often than not, occulted the initial partnership between men and women, as well as the initial glory of what it means to be a woman. Our Song, however, reveals to us these forgotten and lost moments of Creation. More specifically, in our Song, we discover a womans way of love, a womans wisdom in love, in contrast with the rest of the Hebrew Bible where a mostly masculine approach to love is at play, with some notable exceptions of course, our Song being one of them.

But this exploration of a specifically feminine approach to love is at odds with much of feminisms attempt at dismissing sexual difference as a vestige of oppression, or worse as a pure construct without any basis in reality. world?

Rather than discarding sexual difference then, I would suggest fighting back with our own interpretations and commentaries. For centuries, males have done the work of interpreting sexual difference . Is it not high time that we take our place at the hermeneutic table and begin our own exploration of the hidden significations dormant in our feminine bodies ? In fact, as Cixous rightly advises, there should be as many interpretations as there are womens bodies.