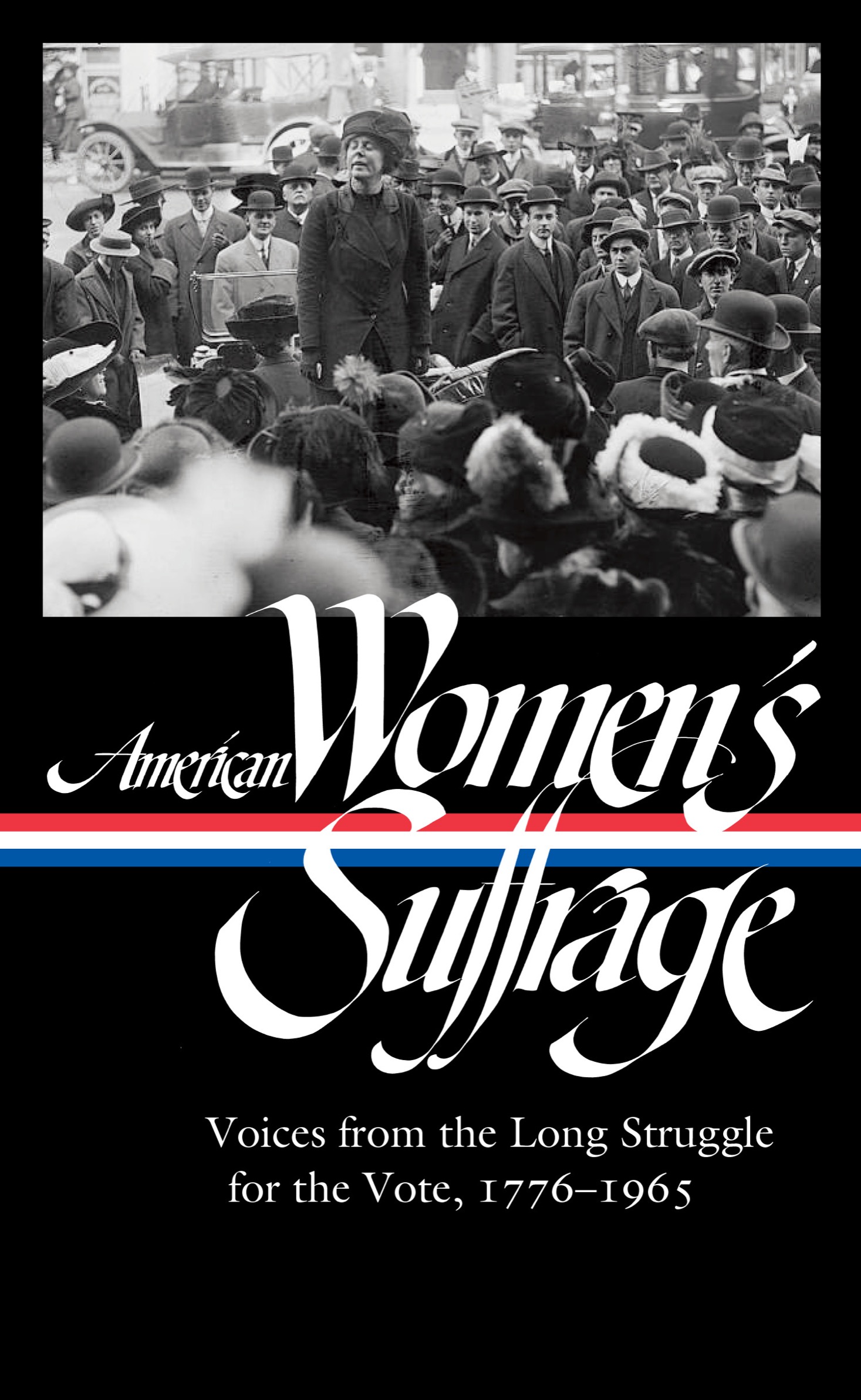

A MERICAN W OMENS S UFFRAGE

VOICES FROM

THE LONG STRUGGLE

FOR THE VOTE

17761965

Susan Ware, editor

LIBRARY OF AMERICA E-BOOK CLASSICS

AMERICAN WOMENS SUFFRAGE

Volume compilation, notes, and chronology copyright 2020 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Published in the United States by Library of America.

Visit our website at www.loa.org.

Some of the material in this volume is reprinted with the permission

of holders of copyright and publishing rights. See page .

Distributed to the trade in the United States

by Penguin Random House Inc.

and in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Ltd.

eISBN 9781598536652

List of Illustrations

Introduction

BY SUSAN WARE

T HE WOMENS suffrage movement had a deep sense of its own history. In many ways suffragists were our first womens historians. From 1881 to 1886, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage produced the first three volumes of what they modestly called the History of Woman Suffrage. (A fourth volume appeared in 1902, and the fifth and sixth in 1922.) These volumes, which total more than five thousand pages, were a combination of narrative history and archive, and the material they contained has fundamentally affected how the story of the suffrage movement has been told ever since. Not surprisingly, more than a few selections in this anthology were first collected in the History of Woman Suffrage.

While we should acknowledge a debt to the suffragists early efforts to preserve and document womens history, the story contained in the History of Woman Suffrage is at best an imperfect guide. Stanton and Anthony had an overt political agenda in compiling those volumes: they wanted to create a master narrative that privileged the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 as the founding moment of a movement focused primarily on securing the ballot, and therefore to solidify their legacy as the main leaders of the movement. In telling their side of the story they consistently privileged sex over race, reinforcing exclusionary racial politics that marginalized the substantial contributions of African American women to the broader struggle. They also practically wrote the contributions of Lucy Stones competing suffrage organization out of history, a slight that the final volumes repeated by focusing on the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) at the expense of Alice Pauls National Womans Party (NWP).

This anthology is dedicated to presenting a broader, more inclusive history of the womens suffrage movement. It does not start the story in 1848 with Seneca Falls, nor does it end with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. It moves beyond the East Coastcentric perspective of much suffrage history to range widely in areas like the West and the Midwest, where many of the early breakthroughs occurred and where local politics far removed from national headquarters was often messier and more complicated than the traditional top-down narrative suggests. It even ventures beyond the borders of the continental United States, putting the suffrage movement in conversation with the global movement for womens rights.

Throughout it includes the voices of a range of activists who were not just white and middle-class. The most prominent belong to African American women, whose speeches, articles, and editorials are well represented in this collection. They are joined by voices of working-class and immigrant activists who shared a more intersectional vision of womens rights that included class and race alongside gender. The centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment in 2020 demands a history that not only documents the past but also speaks to our own times.

Historians often talk of the long nineteenth century, a period of nation-building that stretched from the American Revolution to World War I, or the long civil rights movement, which began with Reconstruction and is still ongoing. When setting the chronological boundaries of the story of womens suffrage, why not a long Nineteenth Amendment? This anthology starts in 1776 with one of the most famous quotations in American historyAbigail Adamss Remember the Ladiesbut then samples a range of lesser-known moments touching on the early history of womens rights and womens suffrage, including the fact that a few women voted in New Jersey until 1807. When Maria W. Stewart, an African American activist, spoke in Boston in 1832, she was the first American woman, black or white, to speak in public about politics and womens rights before a mixed audience that included men and women of both races. Why isnt that moment just as celebrated as the Seneca Falls Convention sixteen years later? Womens rights activism was always in conversation with other movements; it never operated in isolation. Pushing the beginning back before 1848 recognizes those interconnections.

On the other end, the long Nineteenth Amendment framing encourages us not to see 1920 as a hard stop to the story. This anthology extends to 1965 to chronicle womens activism in the post-suffrage era, especially that of African American women, but it could have continued straight to the present, since that activism is ongoing. Historians agree that there was no significant difference in the level or intensity of womens political engagement across the great dividethat is, before and after 1920. The newly formed League of Women Voters taught women how to be citizens, and commentators like Eleanor Roosevelt credited women with improving the tenor of public life. The divisions over tactics that had split the suffrage movement in the final decade before the amendments passage continued to play out, both domestically and internationally, in the debates over the Equal Rights Amendment and protective labor legislation for women workers.

More importantly, the 1920 milestone had very little meaning for various groups of prospective female voters. American Indian women did not become fully eligible to vote until 1924, and Puerto Rican women only in 1935. African American women, most of whom still lived in the South, found their right to vote restricted by Jim Crow legislation alongside black men. For African Americans, as well as Mexican Americans and other minority voters, it was the Voting Rights Act of 1965, not the Nineteenth Amendment, that finally made the difference.

Another priority in this anthology is representing the womens suffrage movement in all its regional diversity. There are practical reasons for this focus: since so many of the early victories occurred in western states, it is impossible to tell suffrage history without foregrounding that region. But it is more than just when certain states gave women the votewe need to look at what was happening politically in those states to understand the specific factors that led to success or defeat. Oregon, Colorado, and Utah are all western states, but they have very different suffrage stories. The West was also where the stories of American Indian women primarily unfolded.