Contents

Guide

Page List

A Journey to the Heart of Physical Reality

ANTHONY AGUIRRE

CONTENTS

O ne afternoon some years ago, I was walking through the snow and thinking about other universes. This goes a bit beyond the minimal job description of a professional cosmologist, but pondering at least our universe is definitely a requirement, and on this particular day I was thinking about other ones. More specifically, I was turning over in my mind the fact that the hospitality provided by our universe depends on many extremely special things. For example, if the electric repulsion between protons in the nuclei of atoms were just a bit stronger, then those atoms, and hence chemistry, and hence life itself, could not apparently exist. And there are many other such coincidences. I had convinced myself that there were fourand pretty much only fourpossible explanations for the fact that the laws of physics seem to be carefully chosen to allow us living, conscious beings to be here.

First, perhaps the laws of physics really were designed for us: when the universe began, it (or some superbeing that created it) had usor at least lifein mind. Second, perhaps it was just an immense coincidence: there was one roll of the dice that specified, among other things, the force between protons, and we just got colossally lucky. Third, it could be that many universes exist with different laws of physics, and we are perforce in one of the universes that allow life. Fourth, perhaps the coincidences are illusory: perhaps life would somehow find a way to arise in any universe, with any possible set of physics.

This bit of thinking pretty much stopped me in my tracks for the following simple reason: any one of the four explanations was rather mind-boggling and exciting. Yet one of them, it seemed to me, had to be essentially correct. There werent any other fundamentally different possibilities to be found. A feeling grew in the pit of my stomach that the Universe really is a pretty mysterious place.

It also struck me that this was not so much a puzzle about the Universe itself, but one that only arises with force when Ior youask the question. The mystery is not about why the Universe has some particular properties rather than others, but about the connection between those properties and our very existence as living, conscious, beings contemplating those properties.

The aim of Cosmological Koans is to explore this strange hinterland that arises between the deep structure of the physical worldfrom the infinitesimal to the largest cosmic scalesand our personal, subjective experience as inhabitants of that world. It is an invitation to explore deep questions in physics through personal experience, and, I hope, to gain some of the sense of mystery, excitement, and wonder that this exploration has brought me. Ive devoted much of my life to physics because it represents a path by which some of humanitys finest minds have approached fundamental questions about how the world works. We are part of that world, and sometimes my own studies bring me experiences, such as that walking in the snow, in which I directly experience the mystery that underlies our world and our lives as part of it. Yet, many peopleeven some professional physicistshave a different experience of physics: as a rather difficult, abstract, and dry subject having little to do with actual experience, and very little to do with beauty and mystery. Even those fascinated with physics, and its exotica of black holes, time travel, quantum paradoxes, and cosmic questions, often consider these to be strange and interesting issues about the world out there, studied and understood only by other faraway people who are, if you will, part of the high priesthood. But the beautiful unity of the worldand the physics that describes itmeans that we are more intimately connected with such things than most imagine.

This book puts forward a rather radical proposal: that not only are you intimately connected with the Universe on the largest scales, but you are central. This is not to deny that you are in some sense an infinitesimal arrangement of dust on one small planet out of billions of trillions in our observable universe, which may well be one of many universes. In this physical sense you are, indeed, ridiculously insignificant. But I will try to convince you that you are also a giant: that youa thinking, conscious beingare part of the community of such beings responsible for giving meaning, and even existence, to the universe you inhabit.

Sometime after my experience thinking about multiple universes, I was recounting itand my thoughts about that experienceto a good friend who happens to be a longtime practitioner of Zen Buddhism. He noted that my experience reminded him of what occurs during Zen koan practice. After we discussed this for a while, it seemed clear that koan practice, while somewhat different in subject matter, was very much along the lines of the process I was looking for. Zen koans as collected in books are vignettes of a sort, that embody teachings about reality as explored by Zen adepts; there are classic collections you can buy at the bookstore. But as practiced, koans were devised as a means by which a teacher can confront a student with a situation that, while initially baffling, can be resolved when the practitioner is able to break through habits of thought and answer the koan in a way that is based on new insight, rather than knowledge or previous experience. And engagement with a koan is always a fully personal and participatory experience.

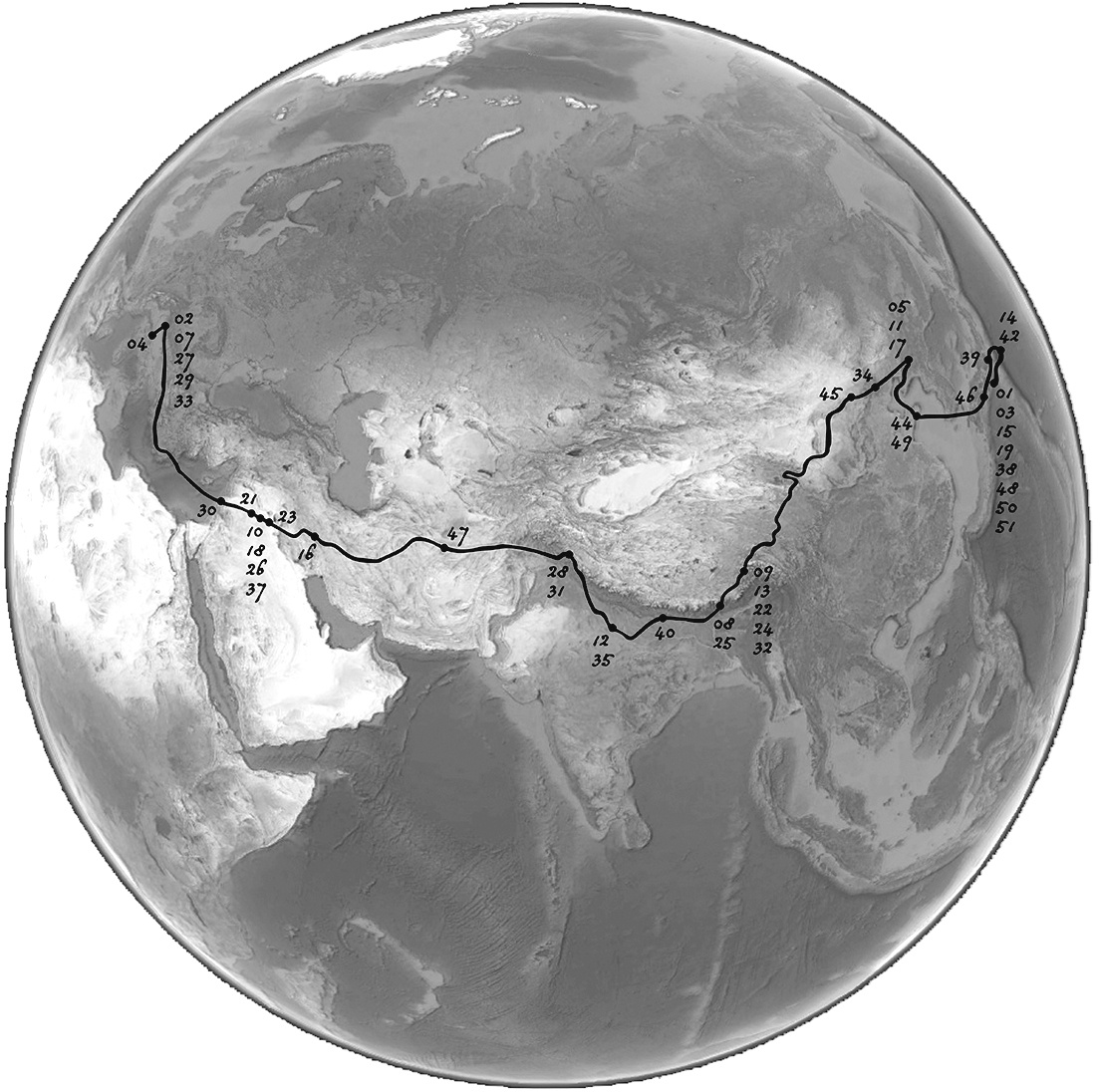

So, I decided to create a set of cosmological koans to explore the connections between us and the unimaginably immense, astoundingly complex, and ultimately mysterious Universe.

The intention of this book is not to compare, equate, or conflate physics and Eastern mysticism, as some books have done. There are real parallels that will emerge, but the adopting here is primarily of method and attitude rather than of content. In both physics and Zen, deep understanding is achieved by breaking through the previous patterns of thought and looking at an issue in a genuinely new way. These patterns can be incredibly tenacious and hidden. For example, Aristotle stated what pretty much everyone believed (and many still do): that objects tend to be at rest, move only when pushed or pulled, and return to rest when the pushing or pulling stops. It took fully 2,000 years for Galileo and others to discover (and convince the world) that the true tendency of objects is to stay in motion. Things come to rest not naturally, but by the action of a specific force, such as friction.

The history of physics is rife with such revolutions in insight: Newtons understanding that the physics of gravity on Earth and in the solar system is the same; Einsteins radical revolution in our understanding of space and time; Heisenbergs discovery of intrinsic uncertainty in fundamental physics, and so on. How were these leaps achieved? Much as in Zen practice, it was by being willing to sit through long hours of confusion and not knowing, often wrestling with apparent paradoxes. And in the end, by finding the courage to perceive something in a new way. As the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer put it: The task is not so much to see what no one has yet seen; but to think what nobody has yet thought, about that which everybody sees.