American Arabesque

America and the Long 19th Century

GENERAL EDITORS

David Kazanjian, Elizabeth McHenry, and Priscilla Wald

Black Frankenstein: The Making of an American Metaphor

Elizabeth Young

Neither Fugitive nor Free: Atlantic Slavery, Freedom Suits, and the Legal Culture of Travel

Edlie L. Wong

Shadowing the White Mans Burden: U.S. Imperialism and the Problem of the Color Line

Gretchen Murphy

Bodies of Reform: The Rhetoric of Character in Gilded Age America

James B. Salazar

Empires Proxy: American Literature and U.S. Imperialism in the Philippines

Meg Wesling

Sites Unseen: Architecture, Race, and American Literature

William A. Gleason

Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights

Robin Bernstein

American Arabesque: Arabs, Islam, and the 19th-Century Imaginary

Jacob Rama Berman

American Arabesque

Arabs, Islam, and the

19th-Century Imaginary

Jacob Rama Berman

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

www.nyupress.org

2012 by New York University

All rights reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Berman, Jacob Rama.

American arabesque : Arabs, Islam, and the 19th-century imaginary /

Jacob Rama Berman.

p. cm. (America and the long 19th century)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-8950-6 (cloth : acid-free paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8147-8950-1 (cloth : acid-free paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4518-2 (pbk. : acid-free paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8147-4518-0 (pbk. : acid-free paper)

[etc.]

1. American literature19th centuryHistory and

criticism. 2. Arabs in literature. 3. National characteristics,

American, in literature. 4. Islam in literature. 5. ArabsRace

identity. 6. National characteristics, AmericanHistory19th

century. I. Title.

PS217.A72B47 2012

810.93529927dc23

2011043495

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of

writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible

for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was

prepared.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper,

and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability.

We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials

to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

| A book in the American Literatures Initiative (ALI), a collaborative

publishing project of NYU Press, Fordham University Press, Rutgers

University Press, Temple University Press, and the University of Virginia

Press. The Initiative is supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

For more information, please visit www.americanliteratures.org . |

To

and their Arab Spring

Contents

Preface

Roadside Attraction

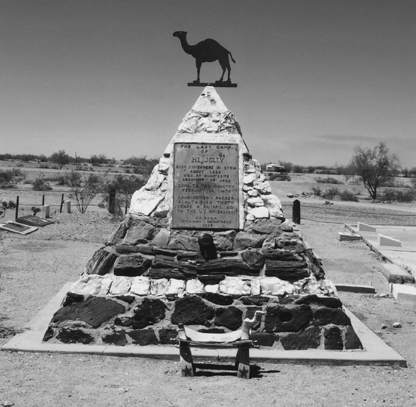

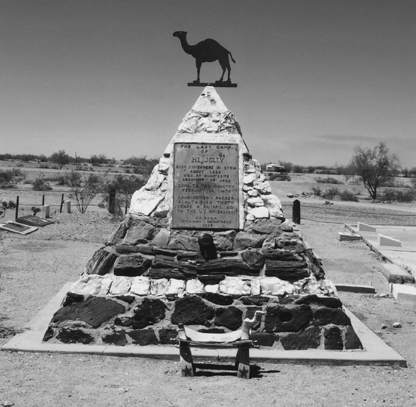

Every January 10, the desert city of Quartzite, Arizona, holds a festival in honor of the Syrian camel driver Hi Jolly. Often cited as the first Arab to make his permanent residence in America, Hi Jolly arrived in the United States in 1856 as part of Jefferson Daviss Fort Tejon Camel Corp experiment. The story of the Camel Corps is a story of fascinating failure. Davis sought to provide a reliable long-distance supply system for the dispersed forts on the frontier and commissioned forty or so camels to be shipped to the American Southwest from the Levant for that purpose. The camels performed well, but the outbreak of the Civil War made their job obsolete. Most of the dromedaries were dispersed in the desert. Eventually they entered into the myth of the American West spawning numerous folk tales and ghost stories. Reportedly the camels were last sighted as late as 1946. A man named Hadji Ali was among the camel drivers who accompanied the beasts of burden from the Levant. When the camels were released, Ali remained in the Arizona territory, occupying a number of colorful jobs before his death in 1902. A pyramidal monument marks Alis gravesite in Quartzites pioneer cemetery (). Atop the tomb is a bronze camel.

The Hi Jolly Memorial is significant not because it marks the burial site of the first Arab to live in America but rather because it demonstrates the role of translation in creating American images of the Arab, in creating American arabesques. The plaque adjacent to Alis tomb explains that because the soldiers whom the Syrian was tasked with training in the ways of the camel could not pronounce Hadji Ali, they changed it to Hi Jolly. Hadji Ali signifies, to a speaker of Arabic, a devout man who has made a pilgrimage to Mecca in accordance with religious duty. Hi Jolly, to an English speaker, is a somewhat ridiculous name that evokes laughter even as it speaks to the incongruity of a Levantine camel driver trying to make his fortune on the nineteenth-century American frontier. Both significations, in their own cultural context, are appropriate nominations for the man behind the name. But between the two there is a cultural gap, one that can only be bridged by attention to the multiple linguistic registers the name evokes.

Figure 1. Hi Jolly Memorial, Quartzite, Arizona. Photograph by Jacob Rama Berman.

The name Hadji Ali is Arab. The name Hi Jolly is an arabesquean imitation of the original that translates its meaning into a new cultural context. American arabesques emerge from the contact between Americans and Arab culture. American Arabesque traces the influence of this contact on the literary formation of nineteenth-century American identity. It is my argument that in the nineteenth century, Arabo-Islamic figures were woven into the very fabric of American culture. To dismiss the presence of referents such as Sherezade, Mecca, Alhambra, and the Sahara in contemporary America as kitsch or as mere adornment is to ignore the deep influence Arab culture has had and continues to have on the American imaginary, both national and personal.

The plaque relating the details of Hadji Alis American name change also relays the tantalizing piece of information that the camel driver had a Greek name, reading His Greek (?) name was Philip Tedro. The bracketed question mark embedded in the official history of Hi Jolly speaks volumes about the vernacular slippages of his identity. Was this putative first Arab resident in America actually a Greek man born in Smyrna who then converted to Islam and took the Hajj (thus acquiring the nickname Hadji)? Research on Philip Tedro reveals several sources devoted to the mans Greek ancestry. These sources claim Hi Jolly as a pioneer Greek American. When later in life Ali/Jolly/Tedro married a woman from Tucson, he insisted on his Greek ethnicity (perhaps in order to avoid racist marriage restrictions). Yet his daughters were purportedly raised as Muslims. Other men in the group of Levantine camel drivers brought over in 1856 are alternately identified as Arabs, Turks, and Greeks in historical accounts. What would it mean if Hadji Ali was not an Arab from Syria but rather a mixed Greek-Syrian who took an Arab name?

Next page