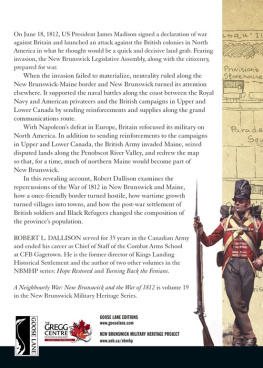

The Road to Canada

The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec

The New Brunswick Military Heritage Series, Volume 5

The Road to Canada

The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec

W.E. (GARY) CAMPBELL

Copyright W.E. (Gary) Campbell, 2005.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Brent Wilson.

Cover illustrations: Front: Reinforcements for Canada Passing Through New Brunswick: A Portion of the 63rd Regiment Crossing Nerepis Valley, ILN UNB. Back: Officers Barracks at Fredericton, Winter, 1834 (1836), by W.P. Kay, NAC C-041071.

Cover and interior design by Julie Scriver.

Printed in Canada by Marquis Book Printing.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Campbell, W. E. (William Edgar), 1947

The road to Canada: the grand communications route from Saint John to Quebec / W.E. (Gary) Campbell.

(New Brunswick military heritage series; 5)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-86492-426-7

1. Roads New Brunswick History. 2. Indian trails New Brunswick History.

3. Military roads Canada, Eastern History.

4. Trans-Canada Highway History. I. Title. II. Series.

FC2461.R63 2005 971.51 C2005-902272-8

Published with the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program, and the New Brunswick Culture and Sports Secretariat.

Goose Lane Editions

469 King Street

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 1E5

www.gooselane.com | New Brunswick Military Heritage Project

Military and Strategic Studies Program

Department of History, University of New Brunswick

PO Box 4400

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3C 1M4

www.unb.ca/nbmhp |

Dedicated to my wife

Carolyn

without whose loving support this book would not have been possible

and

to the memory of

my great-great-great-great-grandfather,

Private William Moran, 104th Regiment of Foot

(late the Kings Orange Rangers and the Kings

New Brunswick Regiment),

who died at Kingston, Ontario, on January 12, 1814,

while on active service,

having made the winter march to Canada,

and two of his sons,

Private John Moran, 104th Regiment of Foot,

who also made the winter march to Canada,

and

Boy and Private William Moran, 104th Regiment of Foot

Contents

Chapter One

Establishing the Route: The Beginnings to 1760

Chapter Two

Planters, Rebels and Loyalists: 1760 to 1785

Chapter Three

Wars and Settlement: 1785 to 1824

Chapter Four

Border Crises and Resolution: 1824 to 1845

Chapter Five

British Strategy Vindicated: 1845 to 1870

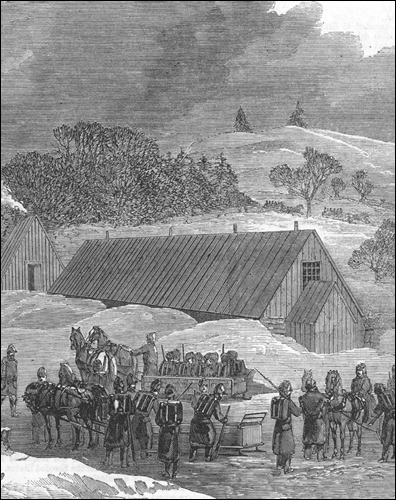

Arrival of a detachment of the 63rd Regiment at the temporary barracks at Petersville, the first stop on the Great Communications Route and now part of Canadian Forces Base Gagetown. ILN UNB

Introduction

It has been said, with truth, that the history of human civilization has been determined and controlled by great rivers.

William O. Raymond,

The River St. John

At noon on Monday, April 12, 1813, a long column of infantry stopped to wash the mud off their legs before marching smartly into the garrison at Kingston, Upper Canada. The 104th Regiment of Foot had left Fredericton, New Brunswick, fifty-two days and over 1,128 kilometres earlier. The march through the wilds of northern New Brunswick in the dead of winter and then along the banks of the St. Lawrence River to Kingston was accomplished without loss of life. One soldier wrote that the men had marched on snowshoes in one of the severest winters ever known undergoing hardships unequalled by any regiment in service during the war. After they passed Quebec, the weather broke; then they marched a part of the distance through mud, water and slush, knee deep. They had come to help save the Canadas from invasion. The march of the 104th became the best-known movement of troops along the Grand Communications Route through New Brunswick, but it was only one of many; until the late nineteenth century, this route formed the backbone of the French and then the British empires in North America.

Today, many people are familiar with the importance of North American rivers such as the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi, but few realize that until quite recently the St. John River was also an important route joining the Atlantic to the hinterland of the Continent. This route ran from the mouth of the St. John River on the Bay of Fundy to the junction with the Madawaska River at Edmundston, up the Madawaska northwards to Lake Temiscouata, and on over the Grand Portage to the St. Lawrence River at Rivire-du-Loup; the British came to call this the Grand Communications Route. Until the advent of railways and steamships, from November to April, when ice closed the St. Lawrence River, it was the only secure way for the French and then the British to reach Canada.

The St. John River system was used for personal travel and trade and by hunting and war parties long before the arrival of the Europeans in the seventeenth century. When French kings began exercising control over Acadia through their governor in New France, the route gained strategic significance in the European struggle for empire. While the preferred method of transportation was by ship, sea communication between Acadia and New France was not possible during the winter months. The only way to pass messages or dispatches or to move troops between the two places during the winter was over the Grand Communications Route, and it was used regularly during the rest of the year by couriers and small parties. The French also made extensive use of the branch route from the St. John River through Lake Washademoak, along the Canaan River, and over the Petitcodiac River portage to communicate with Fort Beausjour, Louisbourg and Port-Royal.

Following the conquest of Acadia and New France in the mid-1700s, the British inherited the route, but for a time they could also use the easier path from Montreal via the Richelieu River, Lake Champlain and the Hudson River to the ice-free port of New York. The American Revolution, however, thrust the Grand Communications Route into prominence once again, and the British made a concerted effort, not just to control it, but to improve it to accommodate sleighs and wagons. The vague definition of the border between Maine and New Brunswick in the 1783 Treaty of Paris made this very difficult. The American interpretation of the boundary placed parts of the Grand Communications Route inside their territory, threatening its integrity, and therefore the British settled Loyalist regiments along its path to help provide security. The route proved its value during the War of 1812, when troops urgently needed to defend Canada, including the 104th, moved over it during the winters of 1813 and 1814.

Next page