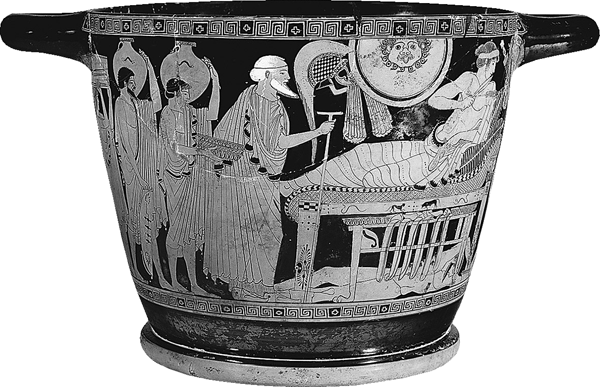

Image and Myth

A History of Pictorial Narration in Greek Art

LUCA GIULIANI

Translated by Joseph ODonnell

University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

Luca Giuliani is the Rector of the Institute for Advanced Study in Berlin and professor of classical archaeology at the Humboldt University of Berlin. Joseph ODonnell is a professional translator based in Berlin.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

English translation 2013 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2013.

Printed in the United States of America

The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften InternationalTranslation Funding for the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, The German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT and the Brsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association).

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-29765-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-02590-2 (e-book)

Originally published in German as Bild und Mythos: Geschichte der Bilderzhlung in der griechischen kunst. Verlag C.H. Beck oHG, Mnchen 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Giuliani, Luca.

[Bild und Mythos. English]

Image and myth : a history of pictorial narration in Greek art / Luca Giuliani ; translated by Joseph ODonnell.

pages ; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-29765-1 (cloth : alkaline paper) 1. Art, GreekThemes, motives. 2. Narrative artGreece. 3. Mythology, Greek, in art. 4. Vase-painting, Greek. I. ODonnell, Joseph, 1960 September 4, translator. II. Title.

N5633.G48613 2013

709.38dc23

2012038002

This is paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This is paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

De toute image, on peut et on doit parler; mais limage elle-mme ne le peut.

R. Debray 1992, 58

We can never understand a picture unless we grasp the ways in which it shows what cannot be seen. One thing that cannot be seen in an illusionistic picture [...] is precisely its own artificiality.

W. Mitchell 1986, 39

PREFACE

The Pictorial Deluge and the Study of Visual Culture

For some time now, critics of contemporary culture have been warning us of an inexorably rising tide of imagery and its pernicious consequences. In their view, the spoken and written word is about to relinquish its traditional preeminence to the image: homo loquens et audiens is on the verge of becoming homo videns. Moreover, they argue, this shift is threatening to extinguish an essentialperhaps the decisivefoundation of human rationality. The higher cortical centers responsible for the conscious processing of information are for the most part not involved in visual perception. And the fact that images are not subject to control by our consciousness makes it all the easier for them to infiltrate and undermine our capacity for reason. Without our being aware of it, they become fixed in our minds and exercise a suggestiveness that shapes the way we think and feel.

It is difficult to argue with the claim that in our media-pervaded environment pictures are playing an increasingly dominant role. But can we conclude from this that we are witnessing a hegemonic transition from the word to the image and that the power of images is threatening to erode the very foundations of our capacity for reason?

The debate about the role of images in the media is certainly not a new one and can be traced back to the advent of press photography more than one hundred years ago.images in daily newspapers. Photo reportage altered the visual habits of the public abruptly and fundamentally by according readers the status of eyewitnesses. This radical shift was interpreted in different ways. Some saw these images as a technologically backed guarantee of pure objectivity and credibility and hailed the photographs as a significant step toward authenticity and genuineness. Others criticized this belief as a seductive illusion, claiming that observers were merely borrowing the gaze of the photo reporter. This was a gaze that viewers had no capacity to shape, and they were thus consuming images that were fundamentally outside their control. As a result, the appearance of immediacy was founded on a deception and promoted comfortable acceptance devoid of any critical attitude.

The dichotomy represented by these two positions is still making itself felt today, even if there has been a significant shift in the focus of discussion. After the Second World War, television rapidly established itself as the dominant mass mediumpeople talking, and the image often serves as no more than a backdrop that is either irrelevant or redundant. Hardly anyone watching the daily news would turn down the sound (whereas, by contrast, in many cases switching off the picture would not mean missing much in terms of information at all).

Communicating information through the mass media faces a specific problem, one which in the first instance has little to do with the opposition between word and image. All mediawhether television, radio or printaspire to a form of reportage that is extensive, rapid, and generally understandable. This is asking a great deal. In order to realize this goal, the complexity of reality must first be reduced to a level where it is intellectually (but also aesthetically and morally) manageable. Coverage that includes news from all over the world and aims to reach a wide audience has no choice but to divide the multiplicity of reality into comprehensible portions and reduce it as far as possible to familiar paradigms. The more quickly news flows, the less time is available for its production and reception, and these conditions do not readily lend themselves to a differentiated analysis or meticulous description of the individual case. Thus, if indeed the mass media do exhibit a certain tendency to present information superficially, then this is already conditioned by the disproportionate relationship between the sheer quantity of information and the time available for its presentation.

Walter Lippmanns 1922 classic, Public Opinion, offers an early and insightful analysis of the mass media and their efficacy. Lippmanns thesis is as simple as it is striking. In every more or less democratically structured mass society, the broad publicand, outside our specific areas of competence, each of us is a member of this publicno longer forms its opinions on the basis of firsthand knowledge and independent reflection. In the modern world individual experience is framed by predefined mental templates and conceptions, which Lippmann defines as stereotypes. Stereotypes condition our perception of reality in the sense that [for] the most part we do not first see, and then define, we define first and then see. In the great blooming, buzzing confusion of the outer world we pick out what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture. Today, Lippmanns analysis is more current than ever. It addresses the fundamental structure of our media-based information society and can certainly not be reduced to a (for its part, stereotypical) critique of the image. In fact, not all images can be defined a priori as stereotypes. Nor is it the case that stereotypes are necessarily or even predominantly communicated in terms of images.

Next page

This is paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This is paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).