Acknowledgments

A huge number of people helped me along the way as I wrote this booknone of whom, of course, is the least bit responsible for any of my mistakes. The UMKC Office of Research Administration funded my visits to the cole Nationale Suprieure dAgronomie de Montpellier and the University of California, Davis. At Montpellier I was welcomed by J.P. Legros and hosted wonderfully by J. Michaux, and in the bibliothque I was particularly well advised by Mme. B. Bye and M. J. Argelles; the Department of Viticulture chair A. Carbonneau was also especially helpful and hospitable. At Davis, J. Skarstad in Special Collections, J. Granett in Entomology, and P. Teller and K. Whelan in History and Philosophy of Science were very helpful. Pittsburgh's Center for Philosophy of Science supported me famously for a semester; in particular, R. Olby, J. Lennox, and P. Machamer gave me exciting things to think about. J. Whiting, D. Downie, A. Walker, and J. Granett (especially!) have been very generous with their time and expertise all along the way. N. Shanks was always there to help, too. Earlier versions of this research were presented at HSSAtlanta, HSSSan Diego, and HSSVancouver; at colloquia in Davis and at Virginia Tech and East Tennessee State; and at the 4th International Pitt Center Fellows Conference, Bariloche, Argentina, June 2000. Finally, I must thank Ann Mylott, who originally pointed me in the direction of medical models of disease.

Introduction

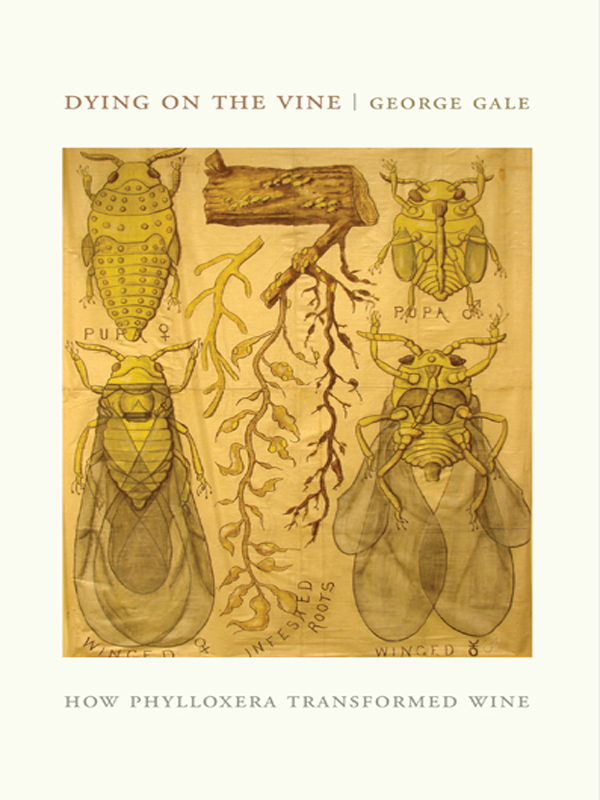

In the mid-1860s, a near-microscopic yellow insect, the grape phylloxera, much remains unchronicled and many lessons unlearned. In the story that follows, I attempt to describe in detail several crucial aspects of the phylloxera disaster for the first time, and along the way to revealoften in a near day-to-day fashionthe lives of some of the major players who successfully fought the battle against the invading devastator of vines.

Three major foci emerge from the story. First, the phylloxera case is the original and best model for studying the dynamics of the interaction between human beings and an invasive species as it colonizes a new habitat. Careful attention to the events of the phylloxera invasion can direct our attention to currently unfolding invasive phenomena. Second, the French response to the phylloxera invasion provides the original model for the genesis and development of one important type of Big Science, that powerful synergistic force combining government, industry, and research institutions. Study of the mechanisms of the birth, growth, and development of Big Science in phylloxerated nineteenthcentury France can teach us much about the nature of Big Science in our own century. Finally, the phylloxera case exemplifies important issues in the history, philosophy, and sociology of science, providing data for controversies that grip these disciplines in their conflicting claims over how science actually works. As we shall see, our battle with phylloxera today is as alive and important as it was more than a century and a half ago.

Yet overarching these three issues is one ultimate, sobering truth: phylloxera is not gone. It is still therein the soil and in the aireverywhere that it has traveled over the last century and a half. The bug is notindeed, it cannot bevanquished. Our struggle with this devastator of vines is never ending, since powering the struggle are the unstoppable forces of evolution. For every defense we muster, the bug ultimately will evolve a successful offense. There is no victory in this struggle, neither for us and our vines, nor for the bug. We must always be alert, especially to the lessons that will be revealed by this book's examination of the past battles. Never again can we let ourselves be lulled into complacency by temporary defensive successes. California's phylloxera disaster of the 1980s and 90s occurred precisely because the defenders got cocky and relaxed their vigilance. If nothing else, this book should show the disastrous consequences of drifting off to sleep in our unending struggle with the bug.

INVASIVE SPECIES

Our biological world is globalizing as rapidly as, and more dangerously than, our economic world. Invasive species, imported life forms as varied as animals, plants, bacteria, and viruses, today wreak havoc on indigenous systems at all levels of organization, from wetland communities to agricultural production systems to human social webs. Introduced into new ecologies where they can make a living, foreign life forms flourish without natural enemies, overwhelming native species, degrading the local ecol ogy, and frequently spreading widely, in the process wiping out whole biological economies. At the moment North America faces invasive threats on many fronts. Examples are ready at hand.

Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), bivalves from Rus sian freshwater lakes, first appeared in the Great Lakes in 1988. Since that time they have spread into watersheds of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, and they are expected to continue to infest the eastern United States and Canada. Lacking natural enemies, they have increased in population, threatening not only local wildlife but also many human enterprises, including water filtration systems, power generation, and food sources, as they clog waterways and machinery.

Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), a European perennial flowering plant, has invaded wetlands throughout the Northeast, destroying native plants such as cattails and degrading the entire wetland ecological system. Since they have no competition, an end to loosestrife's spread is not in sight.

Dutch elm disease (Ophistoma ulmi), an Asian fungus spread by a beetle, has decimated populations of native American elms throughout the eastern United States, changing the look and feel of the entire countryside and cityscape. Although resistant hybrid elms have recently appeared on the market, there is no telling whether this will ultimately remedy the horrible devastation caused by this invasive species.