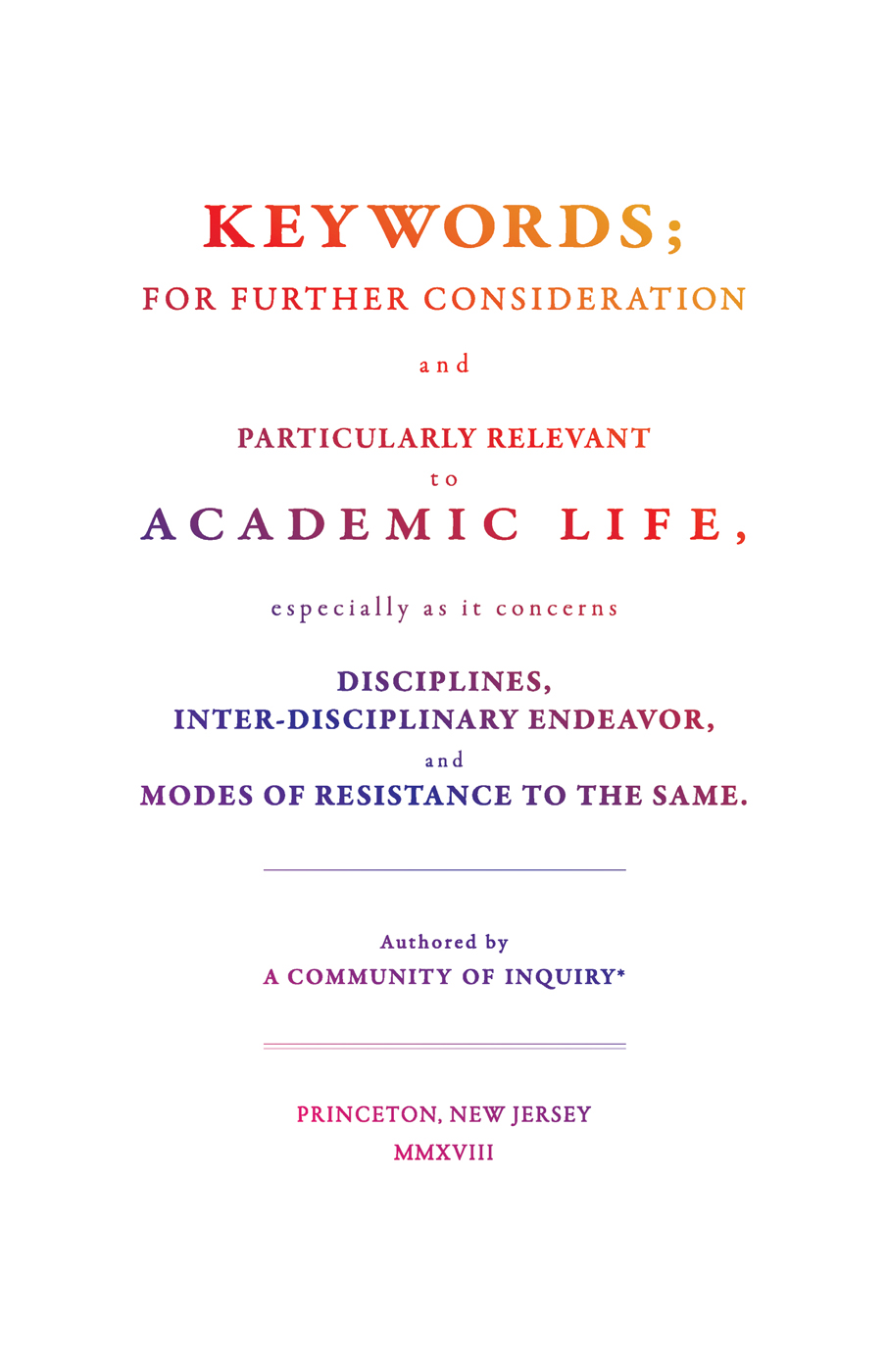

KEYWORDS;

FOR FURTHER CONSIDERATION

and

PARTICULARLY RELEVANT

to

ACADEMIC LIFE

Authored by

A COMMUNITY OF INQUIRY *

IHUM BOOKS

in association with

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

MMXVIII

Copyright 2018 by IHUM BOOKS

All Rights Reserved

Published by

IHUM BOOKS

Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities at Princeton

Princeton University

Princeton, NJ 08544

princeton.edu/ihum

Distributed by

Princeton University Press

41 William Street

Princeton, NJ 08540

press.princeton.edu

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017958697

ISBN: 978-0-691-18183-7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data is available

* The Community of Inquiry consisted of: Paul Baumgardner, D. Graham Burnett, Kate Yeh Chiu, Jeff Dolven, Michael Faciejew, Thomas Matusiak, Candela Potente, Matthew Rickard, Jessica Terekhov, and Enzo E. Vasquez Toral

Editors: D. Graham Burnett, Matthew Rickard, and Jessica Terekhov

Design: Kate Yeh Chiu

With special thanks to: Christie Henry, Brooke Holmes, Anne Savarese, the IHUM Executive Committee, the Center for Collaborative History, and the Council of the Humanities at Princeton University

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro and Century Gothic

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

KEYWORDS

INTRODUCTION

The present text took shape in the shadow (or is it the light?) of two presiding works of criticism that are disguised as glossaries: Raymond Williamss classic Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (1976), and Ambrose Bierces wicked Devils Dictionary (1911). Strange bedfellows, to be sure. The Welsh Marxist gave the world a series of absorbing, studied essays on one hundred terms central to the analysis of social life and cultural productionbound together in a volume that condensed a career of sustained reflection on art, literature, and politics by one of the great progressive intellectuals of the twentieth century. By contrast, the bilious cynicism of Bierce, a hardened American journalist and wounded veteran of the Civil War, eventually found issue in a casual torrent of skewering aperus concerning the vanity and vacuity of modern lifea roll call of zingers, many of which still sting. On the one hand, hopeful and generous learning. On the other, bitter and misanthropic satire.

For all the differences between these two books, each reflects the highly personal and idiosyncratic voice of its author. But the volume before you can claim no such unitary maker. And in that regard, a third glossary project must be mentioned here as an inspiration for the current undertaking: the Collective Dictionary project of the organization known as Campus in Camps, founded by Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti. Campus in Camps functions as a collaborative and politically engaged pedagogical project within the Dheisheh Refugee Camp in the West Bank of Palestine. As part of the ongoing work of bringing a shared awareness to generations of young people in that challenging environment, Hilal and Petti have, over the years, encouraged each campus class to contribute to the collective drafting and redrafting of a set of short essays on key terms shaping the lifeworld of Dheisheh. Words like participation and ownership. Charged words, in context. And the work of reaching a shared understanding of that context is meant to happen in the course of the collaborative defining and redefining of those words.

Each of these three dictionary-like things has contributed something to the spirit of our project. From Williams, we have taken the serious proposition that our critical and productive possibilities are absolutely inextricable from the existence of a shared lexiconthat the richness of our discourse is a function of the richness of that lexicon, which to possess and activate we must attend to with live minds, historical sensitivity, and lots of questions. From Bierce, we have taken the liberating license of irony, together with a commitment to impiety wherever it may work its astringent virtues. From the utopian/emancipatory enterprise of Campus in Camps, we have taken the promising hope that collaborative work on the meanings of words can be a powerful way to build and strengthen communities, and prepare them to work for change.

And so what is this thing that we have made together, thusly inspired? And who were we?

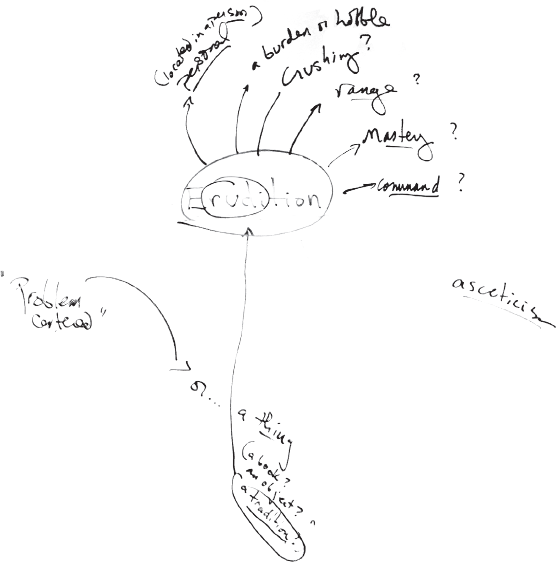

In brief, Keywords;Relevant to Academic Life, &c. emerged out of a graduate seminar taught at Princeton University in the spring term of 2017. The title of the course was Interdisciplinarity and Antidisciplinarity, and it convened under the auspices of the universitys Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities, or IHUM, an initiative less than a decade old and aimed at nurturing experimental and forward-looking Ph.D.-level work across history, literature, philosophy, music, architecture, and the other relevant domains of art and learning. The course description read, in relevant part:

Academic life is largely configured along disciplinary lines. What are disciplines, and what does it mean to think, write, teach, and work within these socio-cognitive structures? Are there alternatives? This course, drawing on faculty associated with the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities (IHUM), will take up these questions, in an effort to clarify the historical evolution and current configuration of intellectual activity within universities. Normative questions will detain us. The future will be a persistent preoccupation.

We were about ten students and faculty in regular attendance, drawn from nearly as many departments. Across the term, we received weekly visits from a dozen distinguished scholars: Lucia Allais, Andrew Cole, Devin Fore, Hal Foster, Eddie Glaude, Anthony Grafton, Federico Marcon, Rachel Price, Eileen Reeves, and others. Each assigned us a classic text from his or her area of expertiseby request, a text that would be of use to us in our effort to understand both the enabling power and limiting perspectives of disciplinary inquiry. The resulting syllabus was arguably eclectic (though not especially diverse: Althusser, Derrida, Du Bois, Eco, Husserl, Kluge, Momigliano, Warburg, etc.), but our conversations were surprisingly focused: again and again we came back to fundamental questions about humanistic inquiryits ends, its means, its past, its present, and its prospects. And this meant a return, again and again, to the primary institution that has sheltered and nurtured humanists: the university.

A summary of the class is beyond the scope of this introduction (though we did draft such a document together over the term). Here it will suffice, perhaps, to say that the course toggled productively between two very different registers. From the outset, there was a strong inclination to ask a frighteningly general and deep question about our work as students and teachers: What is worth doing? What intellectual work is real and good (as opposed to merely tactical or pragmatic within the micro-arbitraging cosmology of Homo academicus)? If that line of inquiry represented the high road of aspiration and vision, we paired such moments of noble folly with a salutary return to the low road of nuts-and-bolts inquiry into the local ecology of higher education: we followed the money; we examined incentive structures; we were skeptical and (at least provisionally, heuristically) disabused of any residual idealisms. The result was, for many of us, both stimulating and clarifying. And if nothing else, the mood of the inquiry fostered a very real sense of shared enterprise.

Next page