WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SOPHIE GEE A hideous crime is committed at a fashionable London society gathering. The victim is the beautiful, innocent Belinda, her attacker is the dastardly Baron, and his weapon of choice is a pair of scissors... Popes mock-epic is the sharp and witty tale of the most famous bad hair day in the history of literature.

Alexander Pope was born in London on 21 May 1688. He was brought up a Roman Catholic at a time when the laws of England were prejudicial towards Catholics and when he was young his family had to move away from the capital as a result of these laws. As a child Pope suffered from a severe illness that stunted his growth.

He wrote from a young age and published his first poems when he was only sixteen years old. He first published The Rape of the Lock in 1712 and its success made him famous. He later expanded the poem in 1714 and 1717. Pope went on to write many more works including translations of Homer, The Dunciad and An Essay on Man. He was also a keen landscape gardener.

Nolueram, Belinda, tuos violare capillos;

Sed juvat, hoc precibus me tribuisse tuis.

OTHER MAJOR WORKS BY ALEXANDER POPE

PastoralsAn Essay on CriticismWindsor ForestThe IliadThe OdysseyPeri Bathous, or The Art of Sinking in PoetryAn Essay on ManMoral EssaysImitations of HoraceEpistle to Dr ArbuthnotThe DunciadThe Rape of the Lock

An Heroi-comical Poem in Five Cantos

Alexander Pope

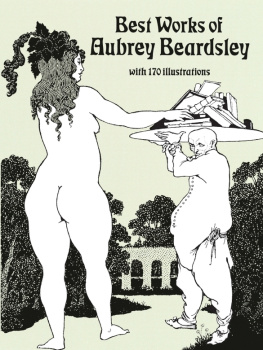

Embroidered with Nine Drawings by

Aubrey Beardsley

With an Introduction by

Sophie Gee

Nolueram, Belinda, tuos violare capillos;

Sed juvat, hoc precibus me tribuisse tuis.

MART.

A tonso est hoc nomen adepta capillo. OVID.

THE DRAWINGS

. T HE D REAM . T HE B ILLET -D OUX . T HE T OILET . T HE B ARONS P RAVER .

T HE B ARGE . T HE R APE OF THE L OCK . T HE C AVE OF S PLEEN . T HE B ATTLE OF THE B EAUX AND THE B ELLES . T HE N EW S TAR

INTRODUCTION

When he was twenty-three years old, Alexander Pope drafted

The Rape of the Locke, the poem that was destined to make him the most famous writer in England. When the poem was first published in 1712 readers were captivated by its brilliance: its perfect couplets, the world of wealth and glamour it depicted a setting that also seemed so brittle it might break apart completely.

No one had written like this before. For the first time, ordinary people could imagine the allure, the privilege, and the fragility of upper-class life in England. And though many would try, no one quite managed to match the poems vitality and freshness until, one hundred years later, an unknown young woman from Hampshire published a novel called Pride and Prejudice. Pope took the idea for the poem from a friend named John Caryll, who told him about a scandal that had just broken concerning two of Englands leading Roman Catholic families, the Fermors and the Petres. The families had become involved in a quarrel, provoked by a lovers tiff between Lord Petre, seventh Baron of Ingatestone, and the lovely, youthful Arabella, eldest daughter of the Fermor family. While at a party in the country, Lord Petre had snipped a lock of Arabellas hair without first asking her permission.

The Fermor family took offence at the prank, more offence than the trifle seemed to merit. John Caryll, who was a mutual friend of both parties, had reasons of his own for wanting to mend the breach. Caryll was also the head of an old and distinguished Catholic family, a self-appointed custodian of English Catholicism. By the early eighteenth century Catholics had been subject to more than a century of prejudice and persecution following the Protestant reformation. The great Catholic houses, once the most ancient, noble and wealthy in England, had shrunk to a beleaguered minority holding out against persecution, imprisonment, and punitive legislation. Caryll was loathe to permit a schism between two such important families.

So he asked his friend Alexander Pope, still largely unknown, to write verses to make a jest of it, and laugh them together again. Pope jumped at the idea, recognising that the story had everything he needed to write a poem that might make his name. Young and obscure, but brilliantly talented, Pope was desperate for fame. But until now it had seemed that Fortune was against him. Like the others, he was Catholic, but in contrast to the Carylls, the Petres and the Fermors, he was socially undistinguished. His father was a textile importer in London, a successful businessman, but modest nonetheless.

Pope was born in London in 1688, but by the time he was four years old his family had been exiled by the passing of a punitive Act that forced all papists to live more than ten miles from Hyde Park Corner. In 1692 the Popes moved to the village of Hammersmith, and six years later to Binfield, in Windsor Forest. As a Catholic, Pope knew that he could never have a university education, obtain professional qualifications, nor, indeed, inherit property of his own. More was to come. When he was about twelve years old, Pope contracted Potts Disease, or tuberculosis of the spine, a condition that was to leave him a lifelong invalid. His growth was stunted, and as a young man he was well on his way to becoming a hunchback.

He was almost always in pain, very often bedridden. In later life his back had to be laced tightly into a brace before he could stand at all. These circumstances seemed to inspire Pope to even greater heights of ambition. His dream was to become as important an English poet as Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare and Milton. Incredibly enough, he was destined to see that dream come true. Pope had a couple of pieces of luck.

Close to his parents house in Binfield lived Sir Anthony Englefield, also a distinguished Catholic, and a man of considerable cultural and intellectual sophistication. Sir Anthony took a shine to the young Pope and engineered introductions to a few noteworthy people, including the famous dramatist William Wycherley. Pope used his acquaintance with Wycherley to insinuate himself into the fringes of literary and artistic life in London, and from there, by sheer force of talent and determination, he rose to the greatest heights of literary celebrity. The second piece of luck, of course, came when John Caryll, also a neighbour, told him about the episode with Arabella Fermors hair. At the time, Caryll may not have known, or perhaps chose not to explain, all of the details. But as it happened, Pope had heard rumours about Arabella Fermor from another source.

Sir Anthony Englefield had two granddaughters, Martha and Teresa Blount, who were close friends of Popes. These girls were also cousins of Arabella Fermor. Although neither as fashionable nor as rich as Arabella, the Blount sisters did belong to the same circle of young, upper-class Catholics who divided their time between the country and London (the Ten-Mile Act had been effectively suspended by the early eighteenth century). Martha and Teresa probably discussed the real situation between Arabella and Lord Petre in letters with other friends, as well as with Pope himself. The exact details have not survived, but it appears that rumours were circulating of a possible engagement between the pair, and that Lord Petre failed to come through with a formal offer. What we do know is that two months before Pope published the first edition of