C ONTENTS

T O

ERNST MAYR

IN COMMEMORATION OF HIS

100 TH B IRTHDAY

J ULY 5, 2004

A REMARKABLE LIFE IN SERVICE OF SCIENCE

L IST OF I LLUSTRATIONS

Reprinted in Alfred Russel Wallace, The World of Life, 1911. By permission of University of Georgia Libraries (UGA).

From Georges Cuvier, Essay on the Theory of the Earth, 1827. By permission of UGA.

From Richard Owen, Paleontology, 1861. By permission of UGA.

Courtesy of G. P. Darwin on behalf of Darwin Heirlooms Trust. English Heritage Photo Library.

From Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches, 2nd ed., 1845. By permission of UGA.

Reprinted in Alfred Russel Wallace, My Life, 1906. By permission of UGA.

Reprinted in Leonard Huxley, Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley, 1901. By permission of UGA.

From 1898 reprint of T. H. Huxley, Mans Place in Nature, 1863. By permission of UGA.

From Ernst Haeckel, The History of Creation, vol. 2, 1876. By permission of UGA.

From Fun, 1872. By permission of UGA.

From American Museum of Natural History, Hall of the Age of Man, 1921 guide leaflet series. By permission of UGA.

Courtesy of the Archives, California Institute of Technology.

From Thomas Hunt Morgan et al., Mechanics of Mendelian Heredity, 1915. By permission of UGA.

Reproduced in Karl Pearson, The Life, Letters and Labours of Francis Galton, vol. 1, 1914. By permission of UGA.

Reproduced from The Scopes Trial: A Photographic History. Courtesy of University of Tennessee Archives and Special Collections.

Courtesy of R. A. Fisher Memorial Trust. Photograph copyright: A. C. Barrington Brown.

From Sewall Wright, The Roles of Mutation, Inbreeding, Crossbreeding and Selection in Evolution, 1932. Courtesy of Genetics Society of America, all rights reserved.

Photograph by Nathan W. Cohen. Courtesy of Betty Cohen. Special Collections, California Academy of Sciences.

Courtesy of Henry M. Morris and John C. Whitcomb, Jr.

Photograph by Jim Harrison (2003). Courtesy of E. O. Wilson.

Modern Library Chronicles

KARENARMSTRONG on Islam

DAVIDBERLINSKI on mathematics

RICHARDBESSEL on Nazi Germany

ALANBRINKLEY on the Great Depression

IANBURUMA on modern Japan

PATRICKCOLLINSON on the Reformation

JAMESDAVIDSON on the Golden Age of Athens

SEAMUSDEANE on the Irish

FELIPEFERNNDEZ-ARMESTO on the Americas

LAWRENCEM. FRIEDMAN on law in America

PAULFUSSELL on World War II in Europe

JEFFREYE. GARTEN on Globalization

MARTINGILBERT on the Long War, 19141945

FRANKGONZALEZ-CRUSSI on the history of medicine

JASONGOODWIN on the Ottoman Empire

PETERGREEN on the Hellenistic Age

JANT. GROSS on the fall of Communism

ALISTAIRHORNE on the age of Napoleon

PAULJOHNSON on the Renaissance

FRANKKERMODE on the age of Shakespeare

JOELKOTKIN on the city

HANSKNG on the Catholic Church

MARKKURLANSKY on noviolence

BERNARDLEWIS on the Holy Land

FREDRIKLOGEVALL on the Vietnam War

MARTINMARTY on the history of Christianity

MARKMAZOWER on the Balkans

JOHNMICKLETHWAIT ANDADRIANWOOLDRIDGE on the company

PANKAJMISHRA on the rise of modern India

PHILIPMORGAN on colonial America

ANTHONYPAGDEN on peoples and empires

RICHARDPIPES on Communism

COLINRENFREW on prehistory

JOHNRUSSELL on the museum

ORVILLESCHELL on modern China

CHRISTINESTANSELL on feminism

KEVINSTARR on California

ALEXANDERSTILLE on fascist Italy

CATHARINER. STIMPSON on the university

NORMANSTONE on World War I

MICHAELSTRMER on the German Empire

GEORGEVECSEY on baseball

A. N. WILSON on London

ROBERTS. WISTRICH on the Holocaust

GORDONS. WOOD on the American Revolution

P REFACE

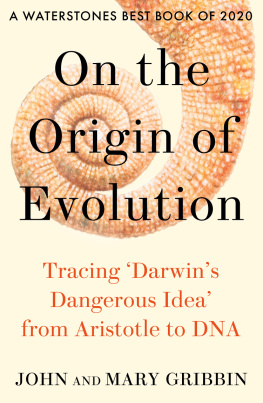

Nineteenth-century evolutionists envisioned the earth as a grand laboratory or workshop of organic development: a shimmering sphere of life spinning in a vast universe. That image inspired a new way of understanding nature. It changed how we view ourselves, one another, and all living things. We became interconnected competitors rather than separate creations. We now live in the shadowor the illuminationof this modern biologic worldview.

The history of modern evolutionary science does not begin with Charles Darwin or even with biology. It begins with breakthroughs in late-eighteenth-century geology and paleontology. Indeed, when Darwin converted to an evolutionary view of biologic origins during the 1830s, he viewed himself as much as a geologist as a biologist. Fortunately, at the time, he did not have to categorize himself with either label, but instead could adopt the broader-brush title of naturalist, which encompassed the various fields of scientific study that he drew upon in formulating his theory of evolution by natural selection.

Darwins theory ripped through science and society, leaving little unchanged by its force. For nearly a century, scientists disagreed sharply among themselves over how evolution operates. Within the scientific community, a consensus answer to this question only began emerging during the 1930s, when a deeper understanding of genetics gave birth to the modern neo-Darwinian synthesis. Scientists still debate the details of evolutionary theory, however, and for many the devil lies in those details. Within the general population, disagreement continues even over whether species evolve, and most particularly over whether humans (or the essence of humanity) originated through purely natural processes from other forms of life. The stakes are enormous; few ideas more profoundly influence us than ideas about our origins. A starting point for any discussion of organic origins is an understanding of how the modern theory of evolution developed. It is a remarkable story of self-discovery that generated concepts affecting the very notion of what it means to be human. And it is far from finished. We will continue to learn more about organic originsand about ourselvesfor as long as we keep our minds open to new ideas in science.

Next page