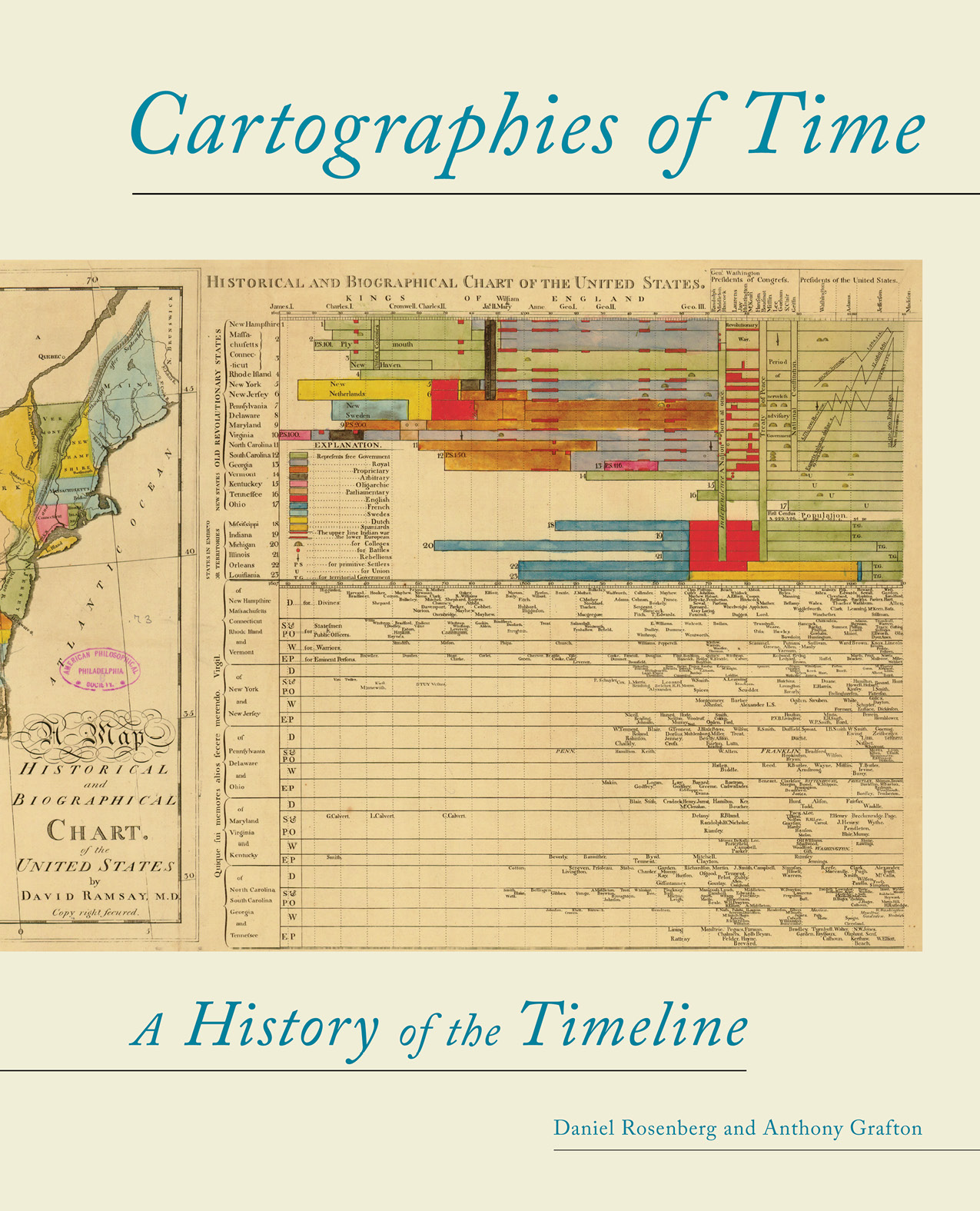

Cartographies of Time

Daniel Rosenberg and Anthony Grafton

Princeton Architectural Press, New York

Contents

Acknowledgments

My deep thanks go to Sina Najafi, Sasha Archibald, Brian McMullen, and Tal Schori, my collaborators on the Timeline of Timelines that appeared in issue 13 of Cabinet: A Quarterly of Art and Culture . This book would surely never have come to be were it not for their genius. The same goes for Susan Harding, Marco Harding, Joseph Masco, and the entire Histories of the Future group. I first began to collect timelines while participating in a seminar that Susan organized at the University of California Humanities Research Institute. In the years since, I have been collecting debtsto the Center for Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture at Rutgers University, the Huntington Library, the Clark Library at the University of CaliforniaLos Angeles, the Clark Art Institute, MASS MoCA, Argos, the Slought Foundation, the Museo Rufino Tamayo, the Center for Eighteenth-Century Studies at Indiana University, the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Oregon Humanities Center. My thanks to the wonderful librarians who have assisted me at these institutions, especially in the Knight Library at the University of Oregon, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at Princeton University, where the greatest part of the research for this project was conducted, especially Stephen Ferguson, Donald Skemer, AnnaLee Pauls, Andrea Immel, John Blazejewski, and Charlene Peacock.

I wish also to thank Alletta Brenner, Theresa Champ, Mike Witmore, Daniel Selcer, Jonathan Sheehan, Arielle Saiber, Sophia Rosenfeld, Miryam Sas, Pamela Jackson, Ken Wissoker, Amy Greenstadt, Steven Stern, Jamer Hunt, Justin Novak, Frdrique Pressmann, Elena Filipovic, Pip Day, Nato Thompson, Dror Wahrman, Michel Chaouli, Martin Jay, Randolph Starn, Eviatar Zerubavel, John Gillis, Harold Mah, Joel Smith, Sheila Schwartz, Neil de Grasse Tyson, Maya Lin, Christoph Fink, Katie Lewis, Jacqui Glanz, Anne Glanz, Astrit Schmidt-Burkhardt, Jim Shaw, Steven Shankman, Barbara Altmann, Julia Heydon, Georgia Barnhill, Michael Paulus, Roy Goodman, Vicki Cutting, James Fox, Lesli Larson, and Eliz Breakstone, as well as the past and pre-sent EMods of the University of Oregon, including Andrew Schulz, David Castillo, Fabienne Moore, Diane Dugaw, Amanda Powell, James Harper, Lisa Freinkel, Leah Middlebrook, and Nathalie Hester. Mark Johnson was an insightful editor for the original proposal for this project. Jeff Ravel did a brilliant job editing my article Joseph Priestley and the Graphic Invention of Modern Time for Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture . Thanks to my colleagues in the Robert D. Clark Honors College, and especially to Joseph Fracchia, David Frank, and Richard Kraus, and in the Department of History at the University of Oregon including Jeff Ostler, Martin Summers, John McCole, George Sheridan, Randall McGowen, and David Luebke, and to Carla Hesse, who has guided me with care for many years. Thanks also to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and to the University of Oregon, who together provided me the opportunity to go to Princeton University to collaborate on this book; to the Princeton University Humanities Council and Carol Rigolot, Cass Garner, and Lin DeTitta; to Barbara Leavey and the Center for Collaborative History and the Department of History; and to Anthony Grafton, whose collaboration, vision, and advice have opened new vistas for me.

My personal thanks to Harry Rosenberg, Barbara Filner, Joshua Rosenberg, Gwendolen Gross, Jacob Rosenberg, Carina Rosenberg, Jack Paris, Judy Cheng Paris, Su-Lin Nichols, Bill Nichols, Charlie Nichols, Will Nichols, and above all to my partner, Mai-Lin Cheng, whose contributions to this project are without measure. My efforts are dedicated to the memory of Amy Jean Kuntz.

Daniel Rosenberg

Many benefactors, friends, and colleagues have made my work on Cartographies of Time not only possible but immensely pleasurable. Heartfelt thanks to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundationabove all to Harriet Zuckerman, Joseph Meisel, and William Bowenfor their imaginative and generous financial support. Funds from the Mellon Foundation and the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin made possible the workshop on chronology in Berlin at which this enterprise was conceived. Lorraine Daston, who cosponsored and hosted the workshop, has my warmest thanks, for her hospitality, for many other kindnesses over the years, and for her erudite and penetrating advice. Further funding from the Mellon Foundation made it possible for Daniel Rosenberg to spend the academic year 20067 at Princeton, and for me to devote much of that year to working with him. Carol Rigolot, Cass Garner, and Lin DeTitta in the Council of the Humanities and Barbara Leavey and Judy Hanson in the Department of History made the complex practical arrangements for our collaboration. Their efficiency, speed in action, and warm hospitality are beyond praise. The extraordinary staff of Princetons Department of Rare Books and Special CollectionsBen Primer, Stephen Ferguson, Paul Needham, Donald Skemer, and AnnaLee Paulshave assembled remarkable resources in Princeton for the study of chronology. Their intelligence, resourcefulness and generosity made the bulk of our research possible, and they have done an extraordinary job of producing many of the photographs for this book. Our friend Robert Darnton, formerly director of Princetons Center for the Study of Books and Media, allowed us to present an early version of our findings at a special meeting of the Centers works-in-progress seminar. Those in attendance responded with warm enthusiasm and helpful criticism to what turned out to be the very first draft of this book: the chronologists whom we study in this book would have recorded that occasion in capital letters and red ink.

Thanks, finally, to scholars around the world who take an interest in the creativity and quirks of early modern erudition, and whose advice, criticism, and exemplary scholarship have been crucial: Daniel Rosenberg, primus inter pares , for the curiosity, passion, and store of learning that have made our collaboration such a joy; and Ann Blair, Jed Buchwald, Max Engammare, Mordechai Feingold, Peter Miller, Philipp Nothaft, Nick Popper, Ingrid Rowland, Wilhelm Schmidt-Biggemann, Jeff Schwegman, Nancy Siraisi, Benjamin Steiner, Walter Stephens, Noel Swerdlow, and the late Joseph Levine.

Anthony Grafton

Chapter 1:

Time in Print

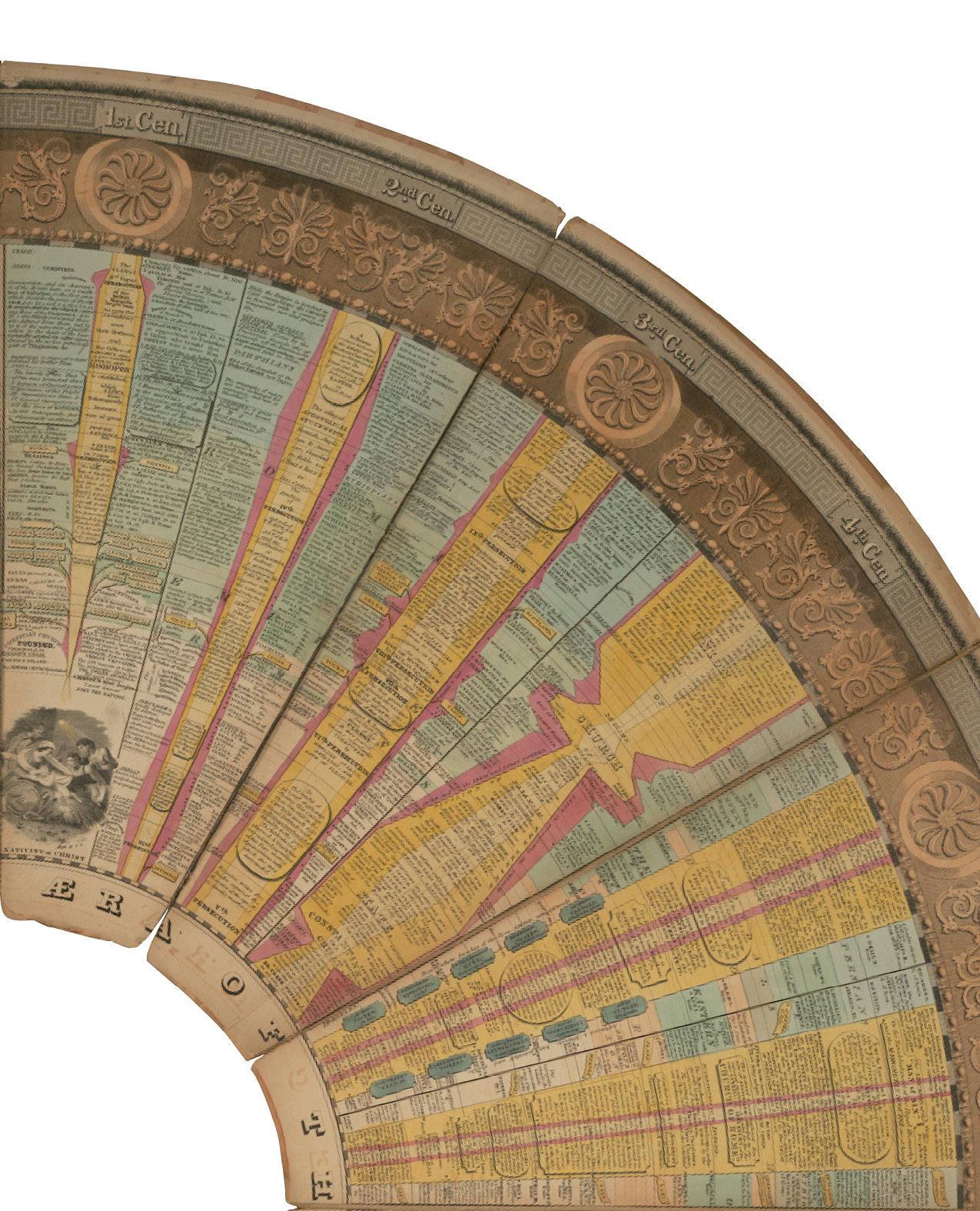

What does history look like? How do you draw time?

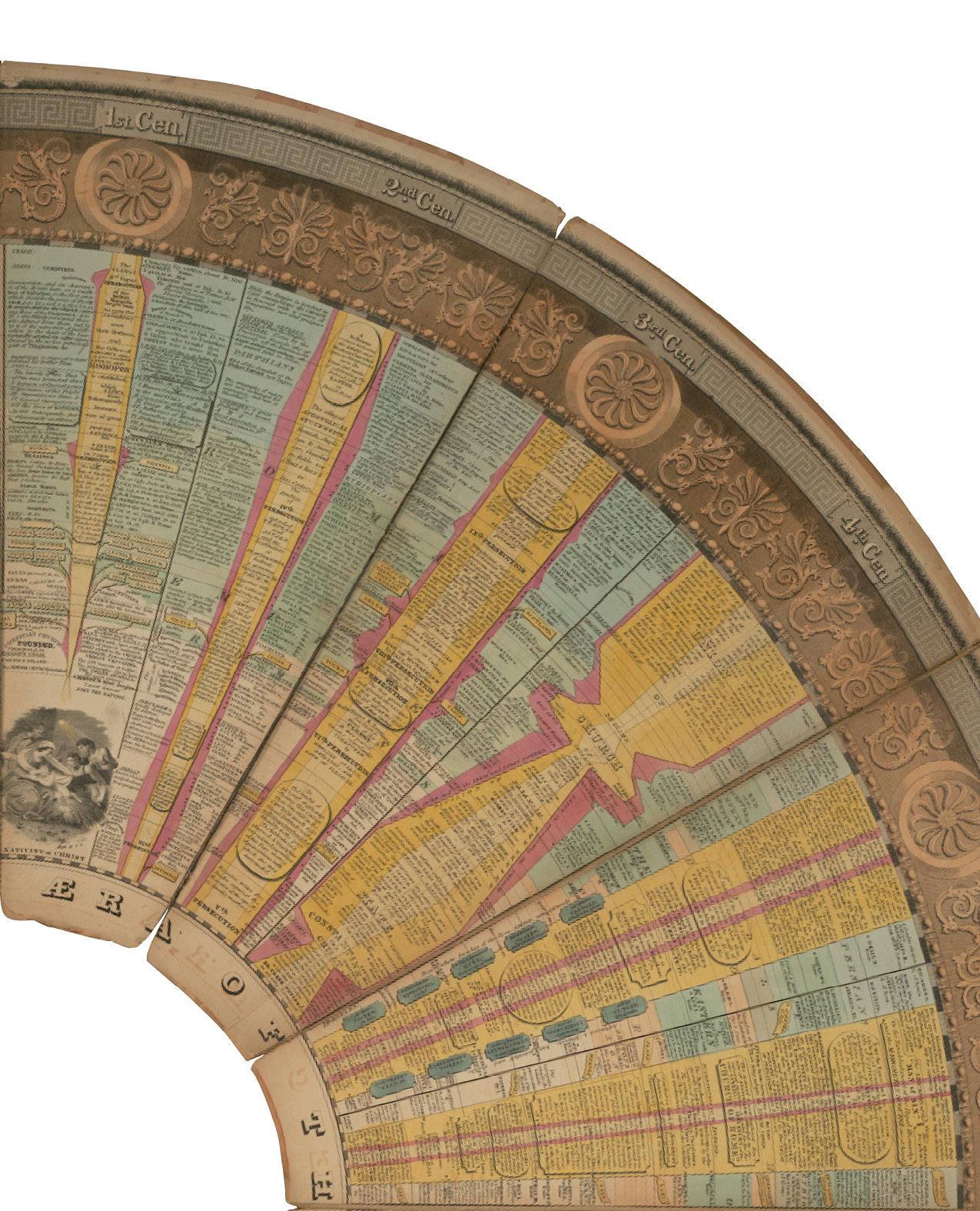

While historical texts have long been subject to critical analysis, the formal and historical problems posed by graphic representations of time have largely been ignored. This is no small matter: graphic representation is among our most important tools for organizing information. This book is an attempt to address that gap.

In many ways, this work is a reflection on linesstraight and curved, branching and crossing, simple and embellished, technical and artisticthe basic components of historical diagrams. Our claim is that the line is a much more complex and colorful figure than is usually thought. Historians will probably appreciate this aspect of the book fairly easily. We all use simple line diagrams in our classroomswhat we usually call timelinesto great effect. We get them, our students get them, they translate wonderfully from weighty analytic history books to thrilling narrative ones.

Next page