HOW THE ZEBRA

GOT ITS STRIPES

Darwinian Stories Told

Through Evolutionary Biology |

LO GRASSET

HOW THE ZEBRA GOT ITS STRIPES

Pegasus Books Ltd

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2017 by Leo Grasset

Translation copyright 2016 by Barbara Mellor

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition May 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole

or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who

may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine,

or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored

in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written

permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-414-5

ISBN: 978-1-68177-476-3 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

W HY DO COWS HAVE HORNS? Why is it that most small antelope females do not have them? Why do men have nipples? Why does a female hyena have a clitoris that is, to the naked eye, indistinguishable from a male hyenas penis?

More generally, the question is this: why do some morphological characteristics that appear to have a function exclusive to one sex also exist in the other? Nipples are a good example: in women they serve to suckle infants, grouping the milk ducts together and providing an interface between the babys mouth and the mothers mammary glands. But in men their function isnt clear: what is the point of a pair of nipples if theyre not for feeding a baby? Perhaps we should simply say, Why not? Does everything have to have a function?

Of the laws that govern the evolution of living beings, selection is the most powerful. This, as well see, is especially evident on the great African savannah. If one individual possesses a slight advantage over another, it will produce more young. If these offspring inherit and pass on the same advantage, the descendants of the advantaged individual will eventually dominate the species gene pool, while those of its erstwhile rival will be consigned to evolutionary oblivion. This, of course, is a simplification: in the real world things are never that straightforward. But to illustrate the theory, lets turn back to the evolution of the nipple.

Suppose that, in the beginning, all men have flat pectorals. Then, one day, a man appears sporting a pair of nipples which emit an intoxicating pheromone. This scent has such a seductive effect on the women he encounters that he fathers 50 per cent more children than his nippleless rivals. If his aphrodisiac nipples are heritable, the children of this fortunate mutant will also be able to sire 50 per cent more offspring, who in turn will go on to produce 50 per cent more great-grandchildren for the mutant and so on down the generations. After five centuries, or twenty generations of twenty-five years, the nipples and pheromones human will have some 3,325 times (1.520) more descendants than the flat-pectorals type: a colossal difference. As long as it can be inherited, even the slightest advantage in the number of offspring will have major repercussions down the generations. Minor effects become cumulative, and in this case, would eventually result in a human population in which all males were equipped with nipples.

In this view of the world, if an organ exists it must have a function. If it appears to be redundant, it is only because we have not yet discovered what that function is. Biologists with this turn of mind might propose that women prefer men who have nipples to men who do not. Or they might suggest a social function: in mothers we know that as a baby suckles it releases a surge of the hormone oxytocin, which promotes feelings of wellbeing and social cohesion and is thought to strengthen the bonding process between mother and baby. In other words, more suckling equals more love for infants, who therefore have better survival rates, which means more babies. These explanations and others like them derive from the belief that everything exists for a reason.

But another school of thought proposes that there are possible evolutionary scenarios in which the male nipple has no practical function at all. All human embryos start out as female: the female sex is the basic form from which the male sex will differentiate itself. The first male hormones do not appear until the eighth week of pregnancy. In other words, the male embryo has to make its male organs using the material available to it, which already tends to the feminine. As the nipples are present from the sixth week, the male embryo is stuck with them. At this point you can reverse the logic: every exclusively male characteristic is an additional attribute, hard won by means of major surges of testosterone and bursts of androgens the classic male hormones. If a female attribute lingers on, and doesnt get in the way or put the male at a disadvantage, it will stay put.

Stringent selection could circumvent this constraint, of course, and drastically favour the male without nipples over his rival who has them but, as this is clearly not the case, we have no reason to lose them.

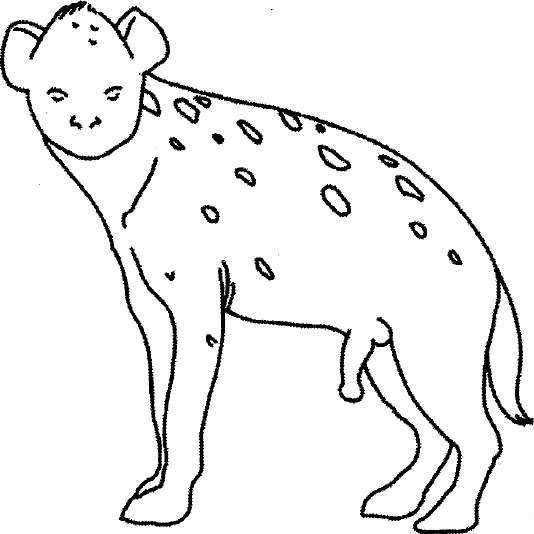

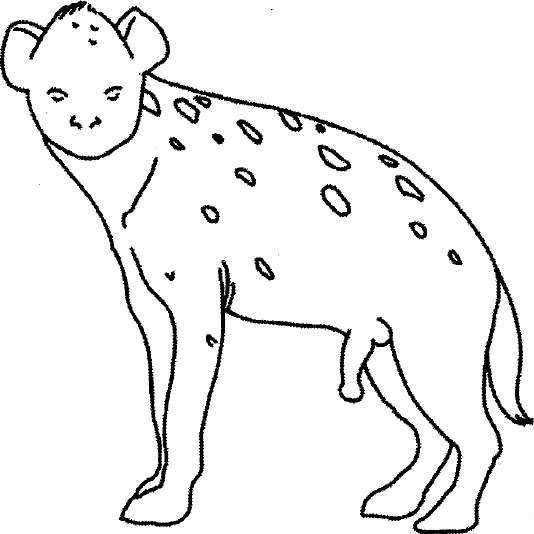

Understanding the factors resulting in a characteristic that appears extraneous is a challenge for biologists. Here are two more examples, both from the savannah: the penis-shaped clitoris of the female hyena, and the horns of the female buffalo.

Viewed with the naked eye, the female hyenas clitoris is indistinguishable from the males penis.

No, you did not misread that: the female spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta, photograph 2) has a clitoris shaped like a penis. It is known in scientific jargon as a pseudo-penis. An imitation, basically, but a seriously good one. In fact, the female hyena imitates the male genitalia in their entirety: she also has a faux scrotum and faux keratin spines (a very widespread characteristic in mammals) on her faux penis, and not only can she get an erection with her clitoris but she also urinates through it. She has no separate vaginal entrance: her entire external genitalia take the form of a male penis. With the naked eye, it is hard to tell the difference between the male hyena and the female.

When it comes to giving birth, this organ causes the female serious difficulty, because her offspring enter the world via this narrow pseudo-penis. As a result, 15 per cent of mothers die during their first labour, and no fewer than 60 per cent of hyena cubs die at birth. From the evolutionary point of view, therefore, there has to be a pretty persuasive upside to justify the presence of this organ. One advantage is that it is difficult for the males to mate with the females by force; even when she is willing. It will take several attempts before the couple manages to find the right position, because he has to insert his penis into her pseudo-penis. For hyenas, successful mating is a whole art in itself, demanding a degree of expertise from the male and so allowing the female all the time she needs to choose her preferred partner.

For a long time it was thought that the female hyenas pseudo-penis was a consequence of the social hierarchy among hyenas: the females are dominant over the males (they are bigger, which helps), and the more aggressive females dominate the sisterhood. Their aggression is controlled by male hormones, and it used to be thought that the struggle for dominance released a higher level of androgens in the females, leading to the accidental appearance of male organs.

Next page