ALSO BY EDWARD D. MELILLO

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2020 by Edward D. Melillo

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Doubleday: Excerpt from Haiku from Introduction to Haiku by Harold Gould Henderson, copyright 1958 by Harold G. Henderson. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Grove/Atlantic, Inc.: Excerpt of The Common Fruit Fly from Mount Clutter by Sarah Lindsay, copyright 2002 by Sarah Lindsay. Reprinted by permission of Grove/Atlantic, Inc. Any third party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited.

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.: Excerpt of Touch Me from The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden by Stanley Kunitz Genine Lentine. Reprinted by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Melillo, Edward D. author.

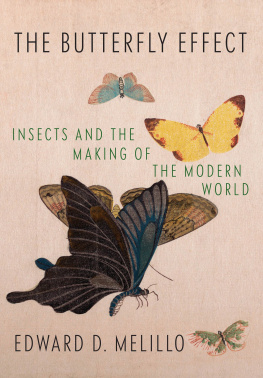

Title: The butterfly effect : insects and the making of the modern world / Edward D. Melillo.

Description: First edition | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2020. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019053343 (print) | LCCN 2019053344 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524733216 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781524733223 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Beneficial insects. | InsectsEcology. | InsectsEffect of human beings on.

Classification: LCC SF 517 . M 45 2020 (print) | LCC SF 517 (ebook) | DDC 595.7/163dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053343

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053344

Ebook ISBN9781524733223

Cover image: Various moths and butterflies by Kubo Shunman. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Cover design by Chip Kidd

ep_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

To my son, Simon Zev Melillo

It is a joyto watch your metamorphosis

Our treasure lies in the beehive of our knowledge. We are perpetually on the way thither, being by nature winged insects and honey gatherers of the mind.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE,

On the Genealogy of Morals: A Polemic (1887)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Fear of insects is among the most prevalent anxieties of the modern age. Homeowners fret about armies of termites or legions of carpenter ants tunneling through walls and floorboards, hotel managers dread bedbug infestations, and parents live in trepidation of lice colonizing the tender scalps of their unsuspecting children. Outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases such as Zika, West Nile virus, yellow fever, malaria, and dengue fever provide forceful reminders of the devastating effects winged pests have had on humanity.

In the realm of food production, insects play a similarly menacing role. The worlds farmers spend upwards of $16 billion annually on insecticides in an endless struggle to thwart invasions of fruit flies, gypsy moths, aphids, locusts, ground beetles, and bollworms, which jeopardize harvests and threaten productivity. Despite this barrage of toxic deterrents, insects destroy an astounding 25 percent of the goods and services produced each year in developing nations. Economists have taken to measuring the impact of these creatures on a countrys economic productivity as a key indicator of modernization.

Insects have often fared no better in the popular imagination. Many Western cultures equate cockroaches, flies, maggots, and fleas with filth, decay, and moral degeneration. English, like other Western languages, hums with pesky bugs: flies in the ointment, butterflies in our stomachs, ants in our pants, and bees in our bonnets. From the barfly getting buzzed at the fleabag motel to the obstinate bug in the system, predatory insects infest the vernacular environment. It is no wonder that so many Hollywood scriptwriters cast swarms of colossal creepy-crawlies as their villains.

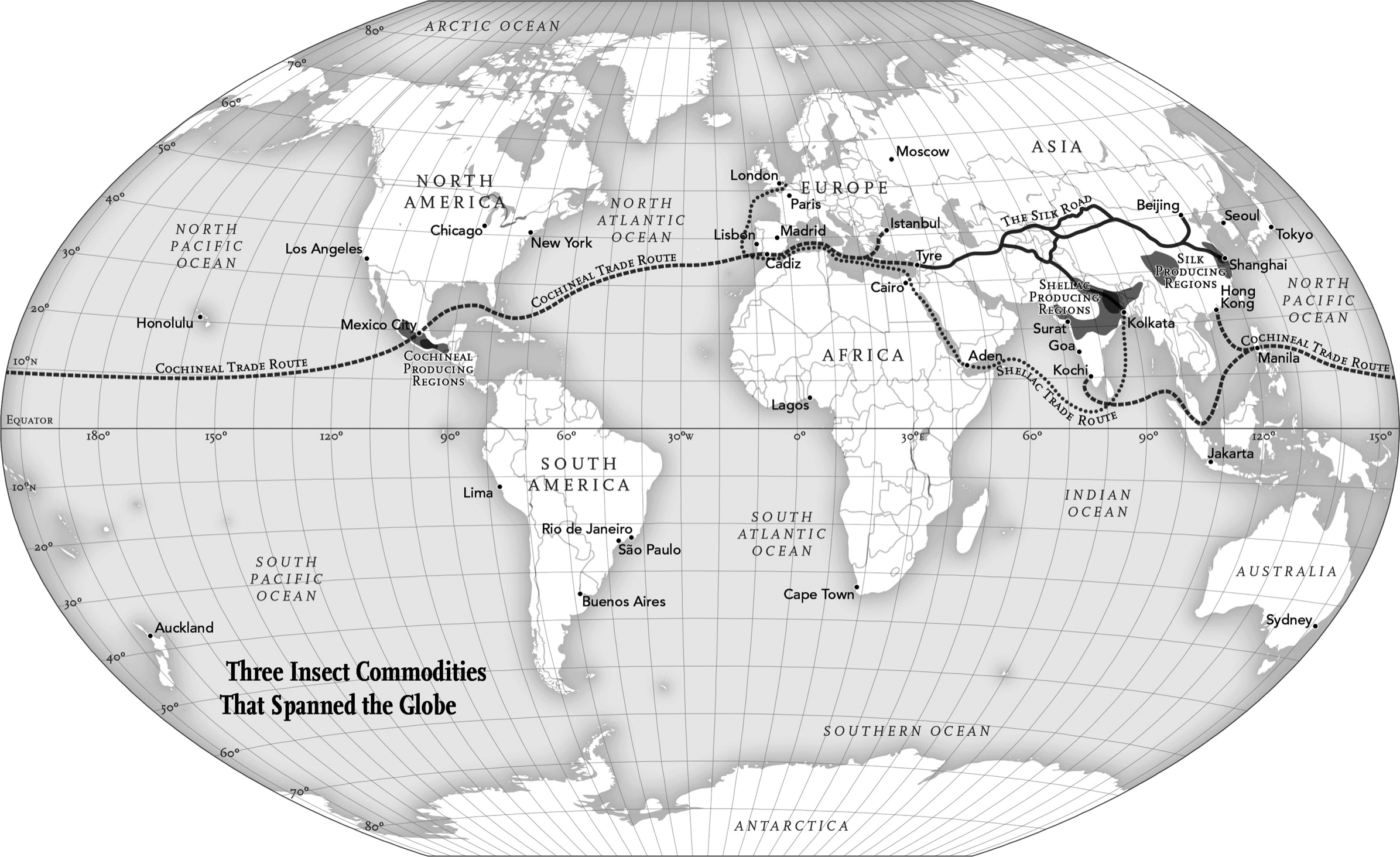

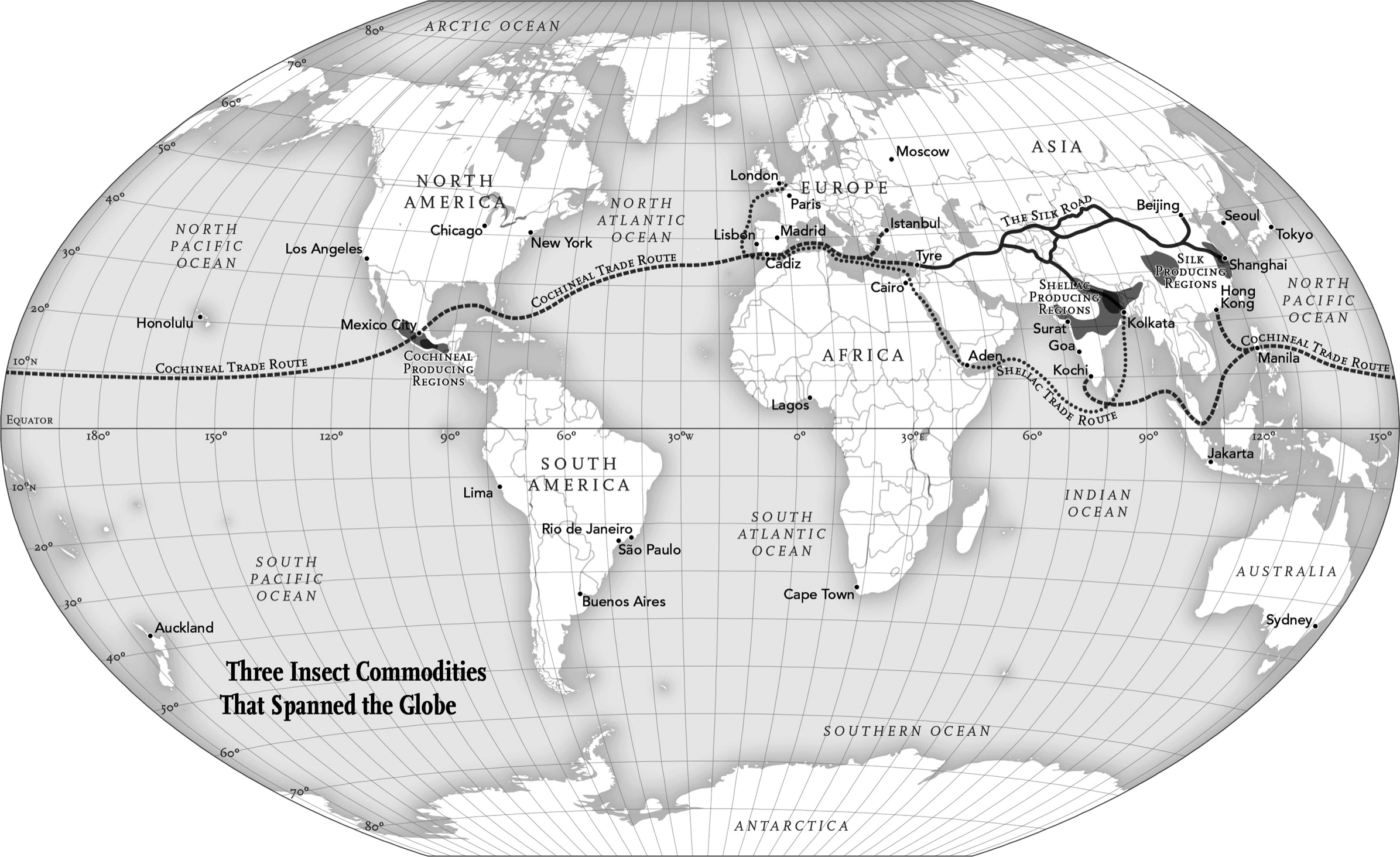

But instead of pursuing the detrimental impacts insects (imagined and real) have had throughout history, this book will take you on a different journey. It traces the long arc of productive relationships between insects and people, revealing a fascinating array of unexpected human dependencies on our six-legged cousins. As it turns out, these tiny creatures are the living factories for many of the commodities that animate the modern world. Insects make many of the substances that pervade our daily lives: fabrics, dyes, furniture varnishes, food additives, high-tech materials, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical ingredients.

When we bite into a shiny apple or enjoy a spoonful of strawberry yogurt, listen to the resonant notes of a Stradivarius violin or watch fashion models strut down a runway, receive a dental implant or get a manicure, we are mingling with the creations of insects. The lac bugs (Kerria lacca), cochineal insects (Dactylopius coccus), and silkworms (Bombyx mori) that exuded the raw materials for the shellac, red cochineal dye, and silk in these products are wonders in their own right, miniature laboratories that defy many of our expectations, expose the limits of our understanding, and reveal forgotten connections with our fellow planetary inhabitants.

In surprising and unpredictable ways, insects also sustain many of the institutions we think of as resolutely modern. Research laboratories, agribusinesses, and trailblazing start-up firms have staked their success on relationships with small winged creatures. Fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) have been crucial to the mapping of the human genome and to many other genetic breakthroughs of the past century. Bees, butterflies, beetles, and flies serve as prolific pollinators, ensuring the survival of three-fourths of the worlds flowering plants and a third of the planets food crops. Crickets, grasshoppers, and mealworms have emerged as inexpensive protein sources, essential to the future prospects of the global food supply. As all of these examples show, six-legged creatures are as integral to the future of our earthly survival as they have been to the apocalyptic visions of pest control companies, chemical manufacturers, and screenwriters.

Invertebrates are not the only stars of this story, however. For many millennia, people in India, China, Mexico, and beyond generated the foundational knowledge on which insect-human relationships are now built. Raising domesticated insects requires an intimate awareness of these creatures daily needs as well as a detailed understanding of how to cultivate the host plants on which these desirable bugs subsist. Rural communities on the margins of the worlds political and economic power centers thus became the unofficial entomologists and the informal botanists of the Age of Discovery. From the sixteenth century onward, Europes imperial administrators failed to comprehend the sophisticated local knowledge that sustained insect-commodity production in many parts of the world.