To Karine, Tuva and SimenI hope your generation takes better care of our six-legged lifesavers...

Nature is nowhere as great as in its smallest creatures.

PLINY THE ELDER, HISTORIA NATURALIS 11, 1.4, C. 79 CE

Preface

I ve always liked spending time outdoors, especially in the forestpreferably in places where signs of human life are few and far between and evidence of our modern impact scarce; among trees older than any living person, trees that have toppled headlong, nose-diving into the springy moss. Here they lie, in prostrate silence, as life continues its eternal round dance.

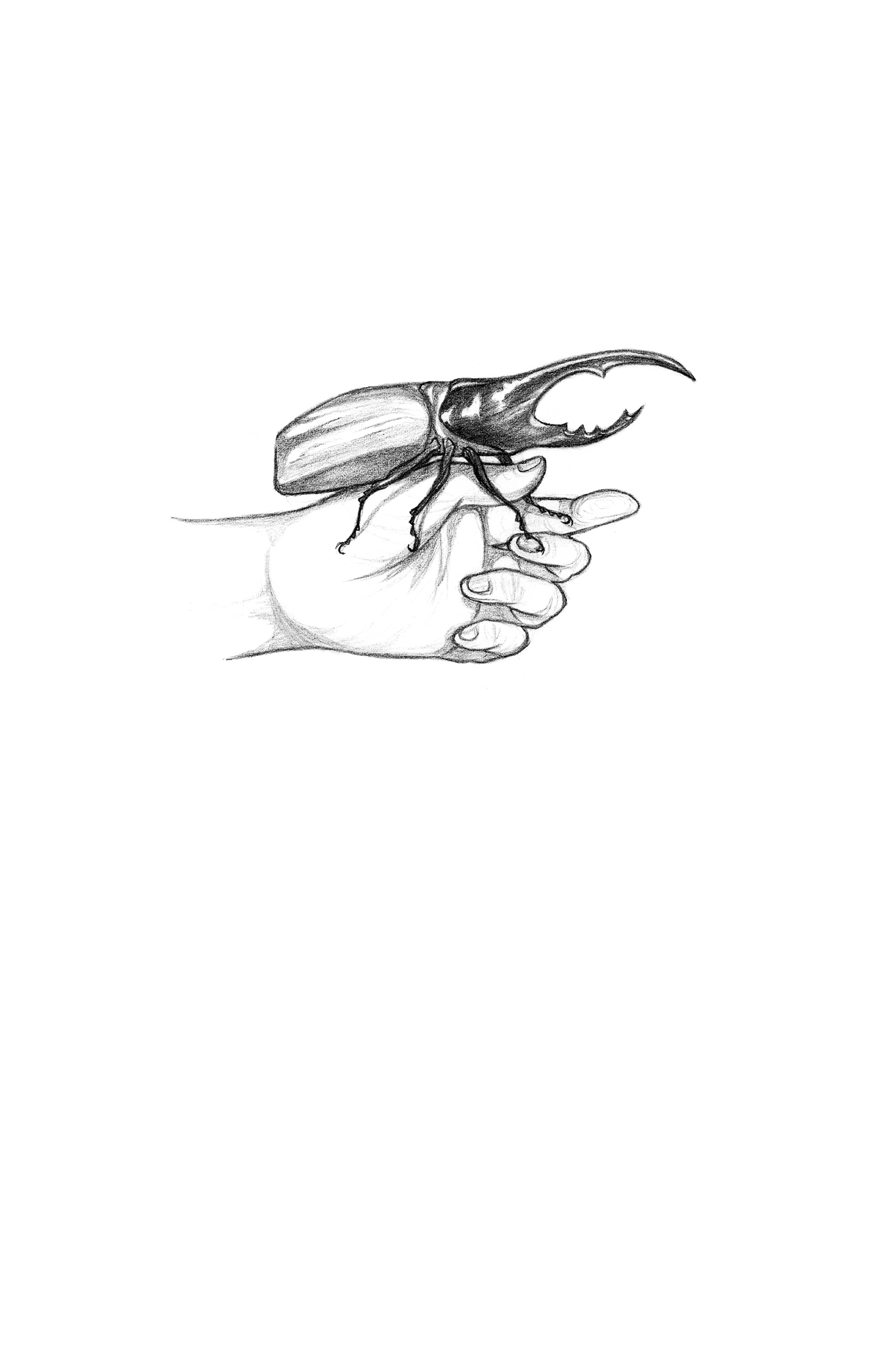

The insects come to the dead tree in hordes. Bark beetles party in the sap that ferments beneath the bark, longhorn beetle larvae trace ingenious patterns on the surface of the wood, and wireworms like tiny crocodiles greedily gobble anything that moves within the rotting wood. Together, thousands of insects, fungi, and bacteria work to break down dead matter and transform it into new life.

I feel incredibly lucky to be able to research such an exciting topic. I have a fantastic job: I am a professor at Norways University of Life Sciences, where I work as a scientist, teacher, and communicator. One day I might be reading about new research, digging deep and losing myself in scientific detail. The next, Im due to give a lecture and have to look for an overarching structure in a given subject areafind examples and illustrate why the issue matters to you and me. Maybe it will end up as a post on our research blog, Insektkologene ( The Insect Ecologists ).

Sometimes I work outdoors. I seek out ancient, hollow oaks or map forests affected to various degrees by logging. All this I do in the company of my wonderful colleagues and students.

When I tell people I work with insects, they often ask me: What good are wasps? Or: Why do we even need mosquitoes and deer flies? Some insects are a nuisance, of course. The truth is that they are a vanishingly small minority compared with the teeming myriads of tiny critters that all do their little bit to save your life, every single day. But lets start with the troublesome ones. I have three answers.

First of all, these annoying insects are useful to nature. Mosquitoes and gnats are vital food for fish, birds, bats, and other creatures. In the highlands and the far north, in particular, swarms of flies and mosquitoes are crucial to animals much larger than themselves, and on a vast scale. During the short, hectic Arctic summer, insect swarms can determine where the large reindeer flocks graze, trample the earth, and deposit nutrition in the form of dung. This has ripple effects that influence the whole ecosystem. Similarly, wasps are useful, both for us and other creatures. They help pollinate plants, gobble up pests whose numbers wed rather keep down, and provide food for honey buzzards and countless other species.

Second, helpful solutions may await us where least we expect them. This applies even to creatures we see as yucky nuisances. Blowflies can cleanse hard-to-heal wounds, while mealworms turn out to be able to digest plastic, and scientists are currently investigating the use of cockroaches for rescue work in collapsed or severely polluted buildings.

Third, many people think that all species should have the opportunity to achieve their full life potentialthat we humans have no right to play fast and loose with species diversity driven by shortsighted judgments about which species we see as cute or useful. This means we have a moral duty to take the best possible care of our planets myriad creaturesincluding those that do not engage in any visible value creation, insects that do not have soft fur and big brown eyes, and species we see no point in.

Nature is bewildering in its complexity, and insects are a significant part of the ingeniously constructed systems in which we humans are just one species among millions of others. That is why this book will deal with the very smallest among us: all the strange, beautiful, and bizarre insects that underpin the world as we know it.

The first part of the book is about the insects themselves. In the first chapter, you can read about their mind-bogglingly rich variety, how they are put together, how they sense their surroundings, and a bit about how to recognize the most important insect groups. Then in chapter 2, youll gain an insight into their rather strange sex lives.

After that, Ill dig deeper into the intricate interplay between insects and other animals (chapter 3) and between insects and plants (chapter 4): the daily struggle to eat or be eaten, in which every creature battles to pass on its own genes. Yet there is still room for collaboration, in countless peculiar ways.

The rest of the book is about insects intimate relationship with one particular species: ushow they contribute to our food supply (chapter 5), clean up the natural environment (chapter 6), and give us things we need, from honey to antibiotics (chapter 7). In chapter 8, I take a look at new fields in which insects can lead the way. Finally, in chapter 9, I consider how these tiny helpers of ours are getting along and how you and I can help improve their lot. Because we humans rely on insects getting their job done. We need them for pollination, decomposition, and soil formation; to serve as food for other animals, keep harmful organisms in check, disperse seeds, help us in our research, and inspire us with their smart solutions. Insects are natures little cogs that make the world go round.

Introduction

T here are more than 200 million insects for every human being living on the planet today. As you sit reading this sentence, between 1 quadrillion and 10 quadrillion insects are shuffling and crawling and flapping around on the planet, outnumbering the grains of sand on all the worlds beaches. Like it or not, they have you surrounded, because Earth is the planet of the insects.

There are so many of them that its difficult to take it in, and they are everywhere: in forests and lakes, meadows and rivers, tundra and mountains. Stone flies live in the chilly heights of the Himalayas at altitudes of 20,000 feet, while mosquito larvae live in the piping hot springs of Yellowstone National Park, where temperatures exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit. In the eternal darkness of the worlds deepest caverns live blind cave midges. Insects can live in baptismal fonts, computers, oil puddles, and the acid and bile of a horses stomach. They live in deserts, beneath the ice on frozen seas, in the snow, and in the nostrils of walruses.

Insects live on all continentsalthough they are admittedly represented by only a single species on Antarctica: a flightless midge that cant survive if the temperature happens to creep up to 50 degrees for any length of time. There are even insects in the sea. Seals and penguins have in their hides various kinds of lice, which remain in place when their hosts dive beneath the surface. And we mustnt forget the lice that live in a pelicans pouch or the water striders who spend their lives scudding six-legged across the open sea.