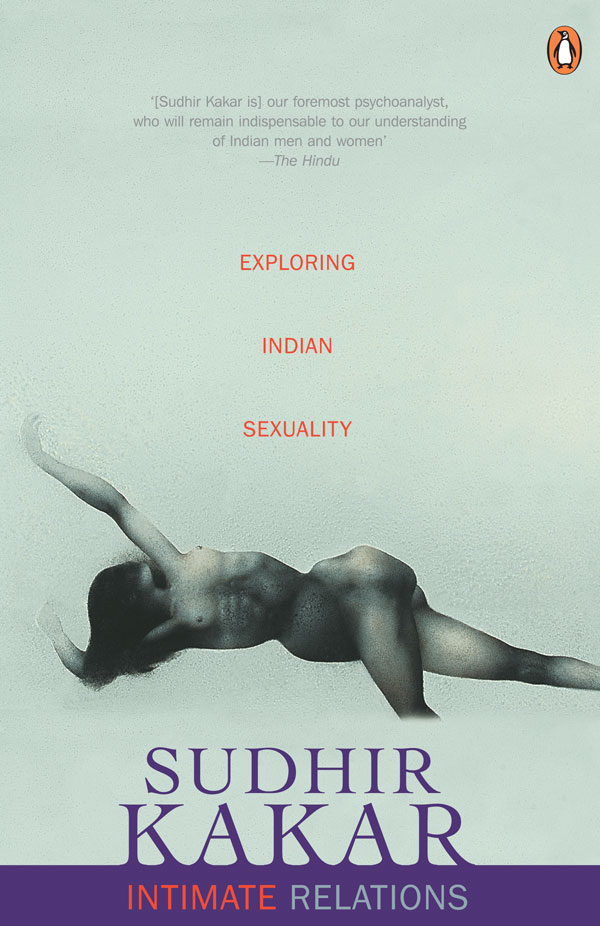

Sudhir Kakar, a distinguished psychoanalyst and scholar, is a senior fellow at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in New Delhi. He has been a Homi Bhabha Fellow, Nehru Fellow and a Fellow at the Institute of Advanced Study, Princeton. He has taught at IITM, Ahmedabad, IIT, Delhi, the Universities of Vienna, McGill and Harvard and now teaches annually at the University of Chicago.

Dr. Kakar is married with two children and lives in Delhi.

1

Introduction

This book is a psychological study of the relationship between the sexes in India. It is about men and womenlovers, husbands, and wivesliving in those intimate states where at the same time we are exhilaratingly open and dangerously vulnerable to the other sex. It is about Indian sexual politics and its particular language of emotions. Such an inquiry cannot bypass the ways the culture believes gender relations should be organized nor can it ignore the deviations in actual behavior from cultural prescriptions. Yet the major route I have selected for my undertaking meanders through a terrain hewn out of the fantasies of intimacy, a landscape whose contours are shaped by the more obscure desires and fears men and women entertain in relation to each other and to the sexual moment in which they come together. What I seek to both uncover and emphasize is the oneirosthe dreamin the Indian tale of eros and especially the dreams of the tales heroines, the women.

Tale, here, is not a mere figure of speech but my chosen vehicle for inquiry and its unique value for the study of Indian gender relations, as indeed for the study of any Indian cultural phenomenon, calls for some elaboration.

The spell of the story has always exercised a special potency in the oral-based Indian tradition and Indians have characteristically sought expression of central and collective meanings through narrative design. While the twentieth-century West has wrenched philosophy, history, and other human concerns out of integrated narrative structures to form the discourse of isolated social sciences, the preferred medium of instruction and transmission of psychological, metaphysical, and social thought in India continues to be the story.

Narrative has thus been prominently used as a way of thinking, as a way of reasoning about complex situations, as an inquiry into the nature of reality. As Richard Shweder remarks on his ethnographic experiences in Orissa, whenever an orthodox Hindu wishes to prove a point The belief is widespread that stories, recorded in the cultures epics and scriptures or transmitted orally in their more local versions, reflect the answers of the forefathers to the dilemmas of existence and contain the distillate of their experiences with the world. For most orthodox Hindus, tales are a perfectly adequate guide to the causal structure of reality. The myth, in its basic sense as an explanation for natural and cultural phenomena, as an organizer of experience, is verily at the heart of the matter.

Traditional Indians, then, are imbedded in narrative in a way that is difficult to imagine for their modern counterparts, both Indian and Western. The stories they hear (or see enacted in dramas and depicted in Indian movies) and the stories they tell are worked and reworked into the stories of their own lives. For stretches of time a person may be living on the intersection of several stories, his own as well as those of heroes and gods. Margaret Egnor, in her work on the Tamil family, likens these stories to disembodied spirits which can possess (sometimes literally) men and women for various lengths of time. An understanding of the person in India, especially the untold tale of his fears and wisheshis fantasiesrequires an understanding of the significance of his stories.

What could be the reasons for the marked Indian proclivity to use narrative forms in the construction of a coherent and integrated world? Why is the preference for the language of the concrete, of image and symbol, over more abstract and conceptual formulations, such a prominent feature of Indian thought and culture? Partly, of course, this preference is grounded in the universal tendency of people all over the world to understand complex matters presented as stories, whereas they might experience difficulty in the comprehension of general concepts. This does not imply the superiority of the conceptual over the symbolic, of the paradigmatic over the narrative modes, and of the austere satisfactions of denotation over the pleasures of connotation. Indeed, the concreteness of the story, with its metaphoric richness, is perhaps a better path into the depths of emotion and imagination, into the core of mans spirit and what Oliver Sacks has called the melodic and scenic nature of inner life, the Proustian nature of memory and mind.

With the declining fortunes of logical positivism in Western thought, the giving up of universalistic and ahistorical pretensions in the sciences of man and society, the traditional Indian view is not far removed from that held by some of the newer breed of social scientists. Many psychologists, for instance, believe that narrative thinkingstoryingis not only a successful method of organizing perception, thought, memory, and action but, in its natural domain of everyday interpersonal experience, it is the most effective. Explanation in psychoanalysis is then narrative rather than hypothetical-deductive. Its truth lies in the confirmatory constellation of coherence, consistency, and narrative intelligibility. Whatever else the analyst and the analysand might be doing, they are also collaborators in the creation of the story of an individual life.

The larger story of gender relations I strive to narrate here is composed of many strands that have been woven into the Indian imagination. There are tales told by the folk and the myths narrated by family elders and religious story-tellers, or enacted by actors and dancers. These have, of course, been of traditional interest for students of cultural anthropology. Today, in addition, we also have popular movies as well as modern novels and plays, which combine the societys traditional preoccupations with more contemporary promptings. I have always felt, at least for a society such as India where individualism even now stirs but faintly, that it is difficult to maintain a distinction between folktales and myths as products of collective fantasy on the one hand and movies and literature as individual creations on the other. The narration of a myth or a folktale almost invariably includes an individual variation, a personal twist by the narrator in the omission or addition of details and the placing of an accent, which makes his personal voice discernible within the collective chorus. Most Indian novels, on the other hand, are closer in spirit to the literary tradition represented by such nineteenth-century writers as Dickens, Balzac, and Stendhal, whose preoccupation with the larger social and moral implications of their characters experiences is the salient feature of their literary creations. In other words, it is generally true of Indian literature, across the different regional languages, that the fictional characters, in their various struggles, fantasies, unusual fates, hopes, and fears, seek to represent their societies in miniature. Indeed, one of the best known Hindi novels of the post-independence era, Phanishwarnath Renus