Joan Crawford, punching the time clock, at the start of Mannequin ()

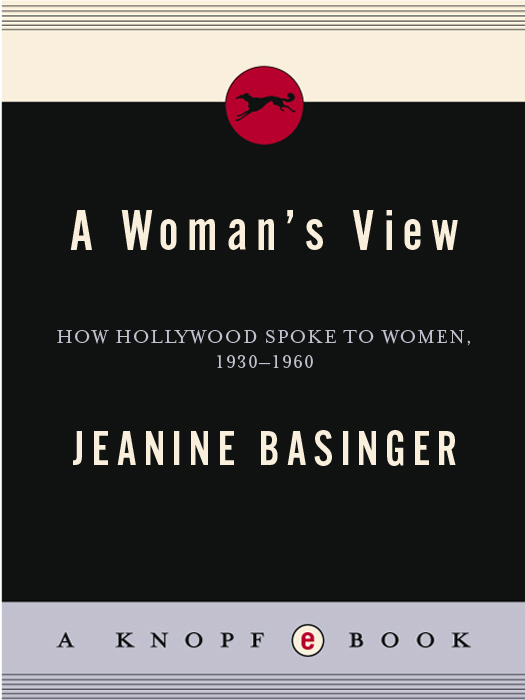

This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Copyright 1993 by Jeanine Basinger

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Owing to limitations of space, acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material will be found following the Index.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Basinger, Jeanine.

A womans view: how Hollywood spoke to women, 19301960 / Jeanine Basinger. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-83154-5

1. Motion pictures for women. 2. Women in motion pictures.

I. Title.

PN1995.9.W6B36 1993

791.43082dc20 93-268

v3.1

FOR MY MOTHER

Sarah E. Pickett Deyling

For her courage, hard work, love,

and intelligence, and for

letting me go to the movies

whenever I wanted to

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

T HIS IS A BOOK that could have gone on forever, and almost did. Once I observed the things I refer to, I found them in every film about women that I saw and wanted to write about them all. Time and space prevented the discussions of literally hundreds of movies that fit my format, and I regret I had no space for Ruby Gentry, The Toy Wife, Torch Song, Marriage Is a Private Affair, Road House, The Star, When Tomorrow Comes, Random Harvest, Lost Angel, The Legend of Lylah Clare, All I Desire, Theres Always Tomorrow and many more.

I thank all the people who found movies for me and shared them: Jeffrey Lane, Richard Teller, Toni Ross, David Kendall, Joe and Kit Reed (intrepid friends wholl watch anything), Richard Slotkin (always a generous and supportive colleague), Bernard Dick, Eric Spilker, and Leonard Maltin. Research help came from Sarah Projansky, Jeremy Arnold, Louis Maggiotto, and Susan Glatzer, and excellent hospitality as well as rare films were provided by Jan-Christopher Horak of Eastman House, Mary Lea Bandy at the Museum of Modern Art, Maxine Fleckner Ducey at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theatre Research, and Jean Firstenberg of the American Film Institute. For help with photos and research, I thank Mary Corliss of the Museum of Modern Art Stills Department, Howard Mandelbaum of Photofest, and Robert Cosenza of the Kobal Collection.

I am grateful to Leith Johnson of the Wesleyan Cinema Archives for his support, and I am forever indebted to Claire LaPila, Administrative Assistant of the Archives, because without her this book would never have reached completion. She was invaluable. And anytime I undertake a project like this, I thank my husband, John, and my daughter, Savannah, who help with everything from ideas and organization to grocery shopping. I want to thank the people at Knopf who worked so hard and well on the book: Iris Weinstein, Karen Mugler, Andy Hughes, and Sarah Burnes. Finally, I must thank my editor, Bob Gottlieb, who, after suggesting the project, accompanied me willingly to far-flung places like upstate New York and Wisconsin, where we confronted that confounding thing known as the womans film. Without him, I would not have known about Weekend Marriage, Sarah and Son, and Mountain Justice, to name only a few, and I would have missed our riveting discussions about Ruth Chatterton and gold lam.

C ONTENTS

T HE G ENRE

W HEN I WAS A CHILD , powers of observation were needed, because no one told you anything. You were awash in a sea of noninformation, and it was up to you to paddle your own canoe to whatever shore of truth you could locate. There were no PBS shows in which friendly animals explained everything from the number 6 to sexual molestation, and there were no colorful little books about Your Appendix and You. We children all coped as best we could, sharing dubious shards of information, discarding them and keeping them as seemed fit. For instance, we all knew that Rae Grebs idea that her parents slept in the same bed so her father could do something odd with her mother was sheer nonsense, but we were reasonably interested in David Christensens idea that a little man lived in the refrigerator to turn the light off and on. Since we lived in a world of alert mothers, we had limited opportunities to find out anything that might be useful to us later in life. We were forced back upon youths most trusted form of information gathering: spying on adults by pretending to play paper dolls while secretly watching and listening. This didnt gain us much (Hush! Its the children!), but fortunately our research was aided by an unexpected, and largely uncensored, bonanza: the local movie house. In those days, parents felt safe sending their children, alone and untended, downtown to the movies. Fortified by Walnettos and popcorn, limited only by our own lack of courage in moments of horror and stymied only by our lack of data to apply to what we saw, we watched in peace and felt like grown-upsa part of the action, a part of the decision-making process. Adults might have been going to the movies to escape, but we children went to get into the thick of things, to be in that place where the real world always said No children allowed.

Thus it was that, like so many before me, I began doing my first serious research into my future life as a female person by going to the movies. I cant say it was an unpleasant jobfar from itbut it surely was a confusing one, because the truth is that the movies of those years contained some highly contradictory information about the womans life. For instance, although women seemed to feel that husbands were the most important thing in the world, men apparently were not to be trusted because they were always dying unexpectedly, getting fired, and running off with chorus girls. These movie women seemed to feel that it was desperately important to be married, yet marriage was an economic disaster in which women had to start baking pies professionally or taking in washing. Women were supposed to be sexually desirable, knowing how to tempt and satisfy men, but they were also supposed to be innocent and pure. How was that going to work? Women needed to be glamorous and lavishly dressed to gain the attention of men and the envy of other women (this latter being particularly important), but they were greedy little beasts if they coveted expensive clothes and jewelry. Instead of asking for things, they should create stunning outfits out of the draperies or produce a cookie jar crammed with about a million dollars worth of egg money to hand over to their man when his automobile factory went broke. Women needed protection because they feared spiders, but they could survive Indian attacks and cholera and fashion failures. They seemed completely capable of bopping villains on the heads with frying pans, and although they screamed a lot, they could run faster than the Wolf Man when he turned up on a moonlit night to try to date them.