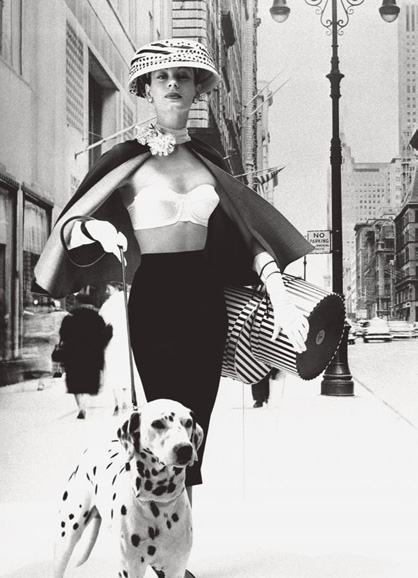

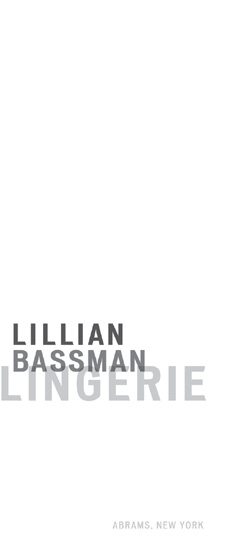

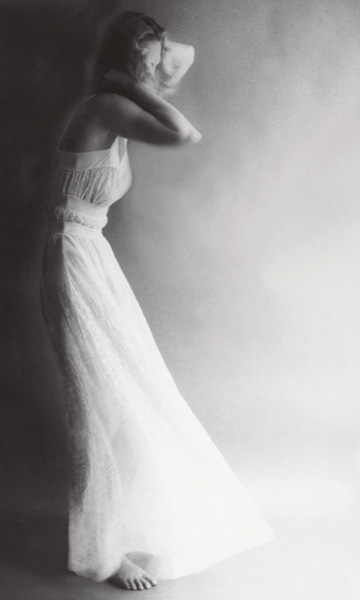

IN 1951, PHOTOGRAPHER LILLIAN BASSMAN described her sensibility to a magazine writer: Im completely tied up with softness, fragility, and the personal problems of a feminine world. This lifelong passion has lent her work its particular esthetic and psychological power. As soon as she became a fashion photographer in the late 1940s, she began to make images of women in intimate settings and quickly established herself as a specialist in lingeriewomens underwear and nightclothes. As viewers have since observed, this body of work rises above its commercial roots to portray a private realm where women appear to be effortlessly self-possessed. Speaking of Bassmans lingerie work in the New York Times, Ginia Bellafante pointed out that the photographs seemed like visual entries in the personal journals of the women photographed.

LILLIAN BASSMAN: LINGERIE is a collection of photographs spanning sixty years that expresses a consistent and penetrating artistic vision, invoking associations with achievements in literature and film.

Whatever the subject, Lillian Bassman stamps each of her pictures with her unmistakable, intense femininity. Almost the archetype for junior-size models, she is tiny, and given to wearing little bodices and full skirts, all designed by herself. Thus, Carmel Snow introduced HARPERS BAZAAR s newest photographer to the magazines readership in the Editors Guest Book section of the October 1948 issue. A year later, on the occasion of her first assignment for SEVENTEEN , the magazines They Worked with Us This Month feature described Bassman in similar terms: She is fast becoming a specialist in feminine photography. Most of her pictures are of lingerie, women dressing, undressing, combing their hair. By 1951, Bassman was well-enough established as a fashion and beauty photographer to merit a perceptive feature in POPULAR PHOTOGRAPHY , where the writer gave her the last word: Im completely tied up with softness, fragility, and the personal problems of a feminine world. Fifty-seven years later, she told Judith Thurman, for a Talk of the Town piece in the NEW YORKER , I think my contribution has been to photograph fashion with a womans eye for a womans intimate feelings.

She was an inveterate observer of women and their ways. This came out, for example, in a euphoric letter that she wrote at the end of her first day in Paris (August 19, 1946): It was too late to get served at the hotel so I decided to walk down the Avenue. I spotted my corner carefully and then proceeded. Its strange how similar and how different French girls are [to American girls]. In the majority, they look like old victory girls of Bway. High pompadours, long hair over their shoulders, skirt at above knee length and heavy dmpy high heeled shoes. It wasnt too light and I was shy about staring too much, so all I got were quick outlines. Bassman, who was even then hatching her escape from art direction into the freer fields of photography, soon lost her shyness about staring. A few days later, she watched the prostitutes make easy pickings of American GIs: Theres no denying a French girl once she spots you alone, its done on the streets, in doorways, anywheres. Theres a special drape to the way her body clings to a man and she takes the initiative on all occasions.

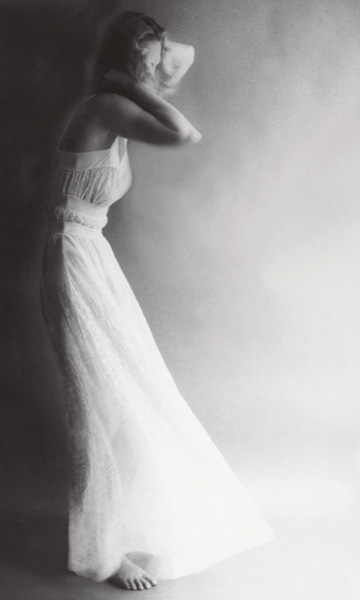

Bassman solved a problem for Snow and her art director, Alexey Brodovitch. Their magazine had scraped through the war years by dint of wit and intelligence fashion was quiescent and advertising was flat. It was clear that the more dynamic postwar scene would present new challenges. In fashion, pent-up demand was met with a resurgence of creative energy. More than anyone else in America, Snow understood this: Gazing at Christian Diors groundbreaking spring-summer collection in Paris in February 1947, she exclaimed, Its such a new look!, thereby coining a phrase. That year, Warners, then Americas largest lingerie manufacturer, registered $12 million in sales, up from a wartime average of $4 million. The lingerie business, which had sunk under a swell of unsold corsets even before the Depression struck, and struggled through the war years, was rising on a tide of bras and girdles. For HARPERS BAZAAR , there were new products to feature and powerful advertisers to please; the traditional visual language to accomplish this bland illustrations and sexless photographswas hardly up to the standards of a publication seeking a fresh vision. Enter Bassman, who understood that an image that evokes a womans experience of undressing is far more compelling than a model posing awkwardly in a brassiere.

In 1948, it was no mean feat to photograph a beautiful woman unselfconsciously undressed. Bassman, who had a gift for cultivating female companionship, made tests with models to gain experience and try out new ideas. I was lucky right at the start. I photographed a model wearing lingerie and tried to make the result soft and flowing. The model loved it, showed the picture to her husband (who happened to be the art director of a big lingerie account), and I landed the account. A writer described her at work in 1951: Bassman works with only a model and a technician. When shes shooting a lingerie photograph, the technician is sent to the corner drug store to drink coffee. Because [she] is not constructing an artificial mood, but trying to make the model feel a familiar one she packs up her camera and heads for the corner of a friends living room or the bathroom of her apartment. Escaping the studio with its hackneyed repertoire of gestures and poses and distracting onlookers, she worked alone with her model in a domestic setting, preferably a room with abundant natural light; like others in her generation, she was adapting the techniques of reportage photography to her fashion and advertising work, giving it a freshness and immediacy that felt new. In the early fifties, she often used a small apartment on East Fifty-Sixth Street that belonged to a decorator friend named William Alexander MacDonald III. Its tall windows with louvered shutters and billowing curtains make fleeting and ghostly appearances in many photographs.

Over time, Bassman adapted to the studiothis coincided with a tighter focus on the human figure. Even here, she would occasionally move furniture into the neutral space defined by seamless paper. Most notable was a sexy matte-black leather slipper chair that she still owns. Whether on location or in the studio, the chemistry between Bassman and the model was key: The models thought about this a lot. It was a sexually very different thing when they worked with men. They felt a charge. They were posing for men. I caught them when they were relaxed, natural, and I spent a lot of time talking to them about their husbands, their lovers, their babies. In the late forties, the Ford Agency, following a fading code of propriety, wouldnt book lingerie shots; its models had to moonlight to work with Bassman, who posed them so that their features were not visible. But change was in the air, and in no time, the typical lingerie sitting involved a top model, totally at ease in the presence of male assistants and art directors.

Next page