Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate Internet addresses and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

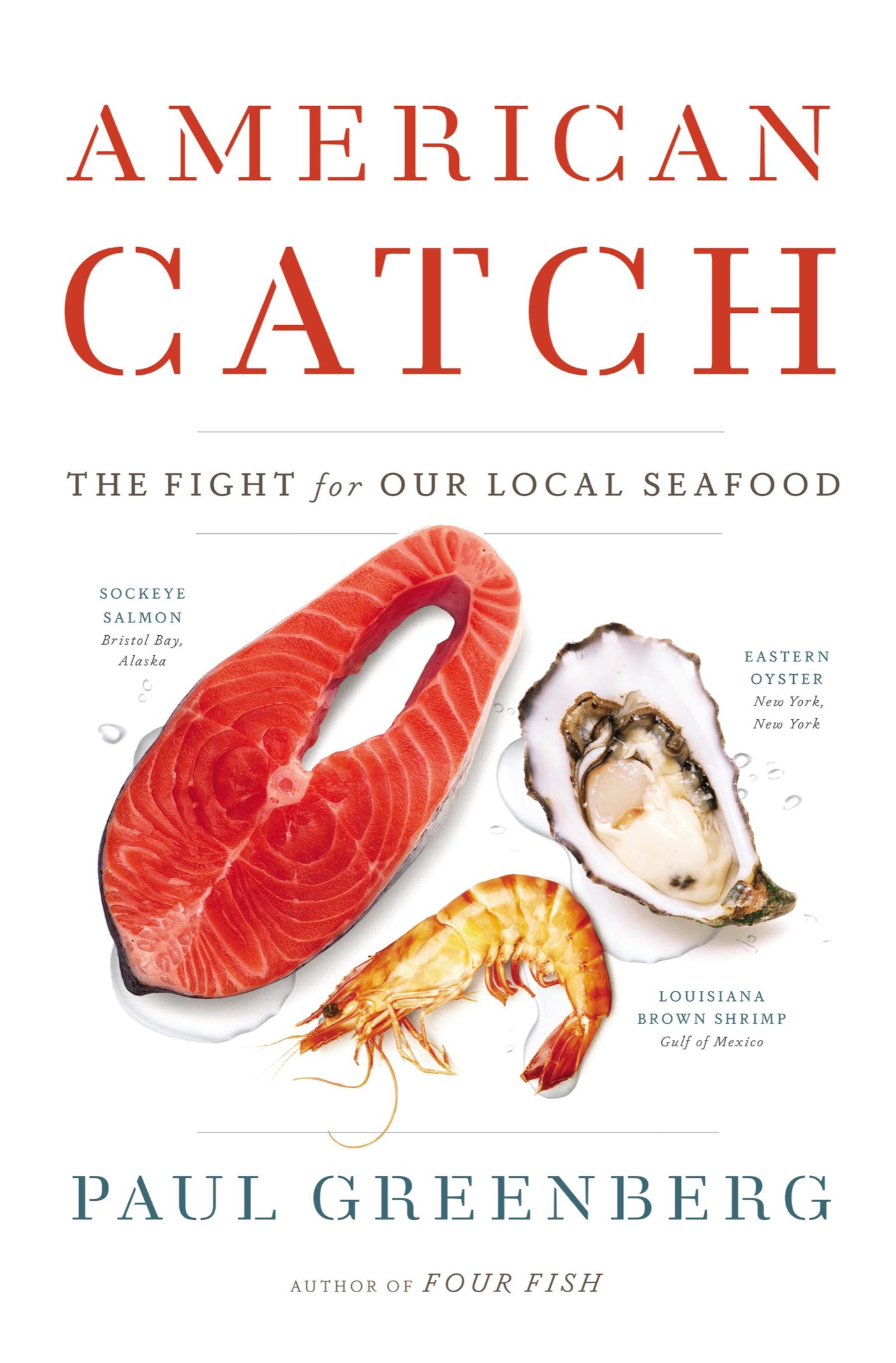

QUESTION: How do you feel about the fact that 91 percent of Americas seafood is coming from abroad?

Introduction

I t is a particularly American contradiction that the thing we should be eating most is the thing most absent from our plates.

Fish and shellfish are today widely recognized by physicians as central to our physical and mental health, and just about every contemporary dietPaleo, Mediterranean, Atkins, South Beach (take your pick)recommends seafood as a key animal protein. Heart disease, Alzheimers, depression, even low sperm count are all conditions that a fish-based diet may help ameliorate. And by all rights this most healthy of foods should be an American mainstay. The United States controls more ocean than any other country on earth. Our seafood-producing territory covers 2.8 billion acres, more than twice as much real estate as we have set aside for landfood.

But in spite of our billions of acres of ocean, our 94,000 miles of coast, our 3.5 million miles of rivers, a full 91 percent of the seafood Americans eat comes from abroad.

Set against the backdrop of the larger American food system, the seafood deficit, is, well, fishy. Many of our most important landfoods are trending in the opposite direction. Corn, anybody? Plenty of itsurpluses of it, in fact. Beef? Enough domestic production to supply every American with around eighty pounds a yearfive times the national per capita rate of seafood consumption. Meanwhile, the paucity of domestic fish and shellfish in our markets and in our diets continues even as foreign seafood floods in at a tremendous rate. In the last half century American seafood imports have increased by a staggering 1,476 percent.

It gets fishier still. While 91 percent of the seafood Americans eat is foreign, a third of the seafood Americans catch gets sold to foreigners. By and large the fish and shellfish we are sending abroad are wild while the seafood we are importing is very often farmed. Two hundred million pounds of wild Alaska salmon, a half billion pounds of pollock, cod, and other fish-and-chips-type species, a half billion pounds of squid, scallops, lobsters, and other shellfish is, every year, being sent abroad, more and more often to Asia; untold tons of omega-3-rich seafood are leaving our shores to help other countries lower their rates of heart disease, raise their cognitive abilities, and lengthen their life expectancy. American consumers suffer from a deficit of American fish, but someone out there somewhere is eating our lunch.

How did we land ourselves in such a confoundingly American catch?

I first began contemplating this question one morning in the summer of 2005. I had recently moved to the far southern end of the island of Manhattan to what the seafaring Dutch had called New Amsterdam but which is now more sterilely christened the Financial District. This lifeless agglomeration of concrete and glass was not at first glance an ideal neighborhood for a writer like me whose subjects are nature and fishing and seafood. But I liked the fact that just on the other side of the skyscrapers the water lay in three directions. I was intrigued that the place where I now made my home was Americas original seaport, the very spot where some of the first American seafood had been landed.

I quickly realized I was deluding myself. For a week I followed the routes that most people traveled in my new neighborhoodup Broadway, past banks and brokerage firms, past the bare asphalt slab called Zuccotti Park. On the site of the New Amsterdam colony, there was now a depressing convergence of fast-food franchises and an oddly duplicative march of bad shoe stores. I stared into the empty pit at Ground Zero and tried uselessly to find some connection to the place like a mariner throwing out an anchor into muddy bottom. The tines found no purchase.

Finally, at the beginning of the second week in my new home, I rose early and set out by bicycle to get a broader feel for this empty-feeling place. Choosing the rising sun as my direction, I turned east, against traffic, at the street that in New Amsterdam days had been called De Maagde Paatjethe Maidens Pathso named because it was the chosen route for Dutch girls bringing their washing down to the East River on laundry days. Today called Maiden Lane, it brought me to Pearl Streetonce Parelstraatan appellation that derives from the time when the road was paved with native oystershell. As I coasted along Pearl, I skirted over landfill that had long ago buried a swatch of salt marsh known in colonial times as Beekmans Swamp. At Dover Street, I headed east again until I arrived at Water Street. The street once marked the waters edge, but now after landfill had widened the city considerably Water Street was several blocks from the water.

But just past Water the feel of the neighborhood started to change and the ghost of a former incarnation started to reveal itself. At the corner of Dover I came across a red clapboard building that I later learned was one of the oldest functioning public houses in New York. Beyond this distinctly maritime-looking tavern stood a row of crotchety old buildings, all from the early 1800s. Hazy stenciling could be made out on a few: Joshua Atkins & Co. Shipchandlers, Joseph C. LaRocca & Sons Shellfish & Seafood. From Dover I went east to Front Street and then tacked south to Peck Slip, a grand plaza in disrepair that petered away and dumped me out onto South Street.

There before me stood a metal warehouse built during the Great Depression. Weeping with water stains, it bore a straightforward, working persons declaration of purpose on its facade:

FULTON FISH MARKET CITY OF NEW YORK

DEPARTMENT OF MARKETS

I had happened upon what had been the most storied and voluminous seafood market in the world and nobody seemed to care that it still existed.

Once upon a time, before the island of Manhattan had any physical connection to the mainland, the Fulton Fish Market was the primary point of entry for nearly every piece of seafood New Yorkers ate. Clunky barges, flat-bottomed oyster skiffs, broad-beamed Hudson River sloops all made their way to this weigh station and docked at buildings that were inherently more geared toward the sea than to the land. There, all of this wild product was off-loaded and transformed into forms the public would recognize as usable food for the larder. Oyster shuckers by the dozens queued up in the stretch that is now covered by the FDR Drive. Prehistoric-looking sturgeon, five feet long and armored with weird cartilaginous shields, were stacked like cordwood in the hulls of fishing boats from as far away as Kingston and sold in pearly white chunks as Albany Beef. Shad-cutters with the particular skill to convert an intrinsically gristly mess into a smooth boneless fillet worked in the early-morning hours and laid out their product alongside the pinkish sacks of roe, smoked or raw depending on the taste of the client at hand.

![Mila Mason - Salmon 365: Enjoy 365 Days With Amazing Salmon Recipes In Your Own Salmon Cookbook! (Best Seafood Cookbook, Seafood Soup Cookbook, Seafood Cookbook For Beginners, Grilled Seafood Cookbook) [Book 1]](/uploads/posts/book/288400/thumbs/mila-mason-salmon-365-enjoy-365-days-with.jpg)