Greenberg - Language in the Americas

Here you can read online Greenberg - Language in the Americas full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: America;Amerika;Amérique;Indianersprachen, year: 1987;2013, publisher: Stanford University Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Language in the Americas

- Author:

- Publisher:Stanford University Press

- Genre:

- Year:1987;2013

- City:America;Amerika;Amérique;Indianersprachen

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Language in the Americas: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Language in the Americas" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Language in the Americas — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Language in the Americas" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

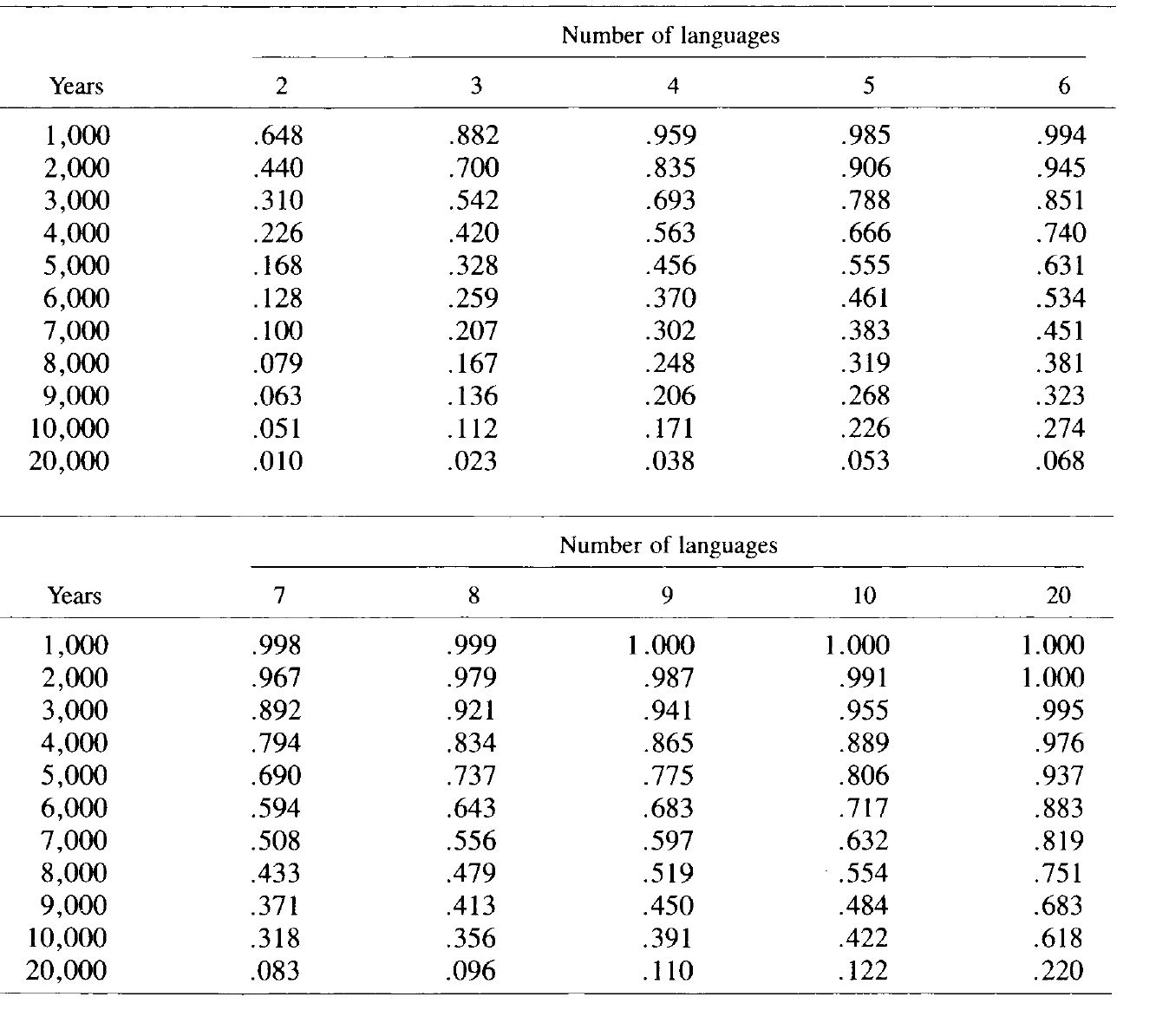

With a large proportion of the vocabulary recoverable by comparison even after a great lapse of time, it becomes possible to compare genetically defined groups of languages with other, similar groups to arrive at still deeper classifications. The general mathematical model outlined below shows how multilateral comparison increases the proportion of recoverable vocabulary as the number of languages compared increases. In fact, multilateral comparison is an even better tool than an examination of the model might suggest, for the semantic criterion is applied strictly in glottochronology; in a standard list of 100 or 200 basic words, only those pairs that are the best translation of a given item are counted as cognates. But because semantic change, like other processes of change, has a cumulative effect over time, many more cognates are in fact recoverable even when they have undergone semantic shifts. An example is the so-called Hund -dog phenomenon. In English, the word hound, cognate with German Hund, still exists but does not appear in a glottochronological comparison.

The theory behind glottochronology is that if we take a list of, say, 200 basic words (and such a list has been devised), the rates of retention of words on this list in their original meanings over a given time period will be reasonably similar in historically independent cases. By examining a number of documented cases, a retention rate variously calculated at .80-.85 for 1,000 years has been ascertained (with a probable error based on the variability among the test cases); the value .80 is the one used here. If, after 1,000 years, 80 percent of the wordlist has been retained, then in the next 1,000 years 80 percent of what is left will be retained, so that the rate of retention of the original vocabulary is .80 .80 or .64 (.802), In general, if t is the number of millennia, the retention rate is the exponential function .80 t .

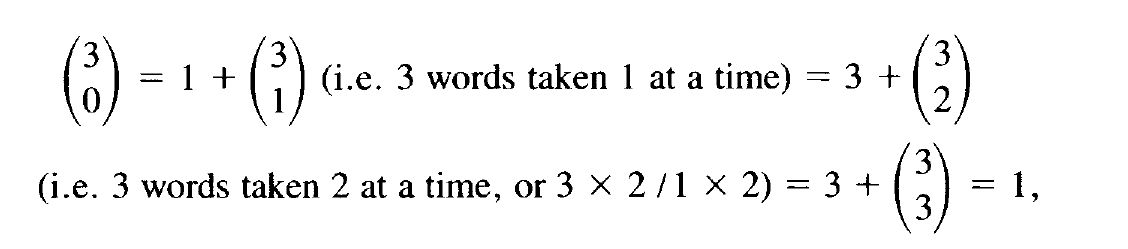

If we now compare two languages that have a common origin, each replacing vocabulary independently at this rate, then after t millennia the common vocabulary will be .80 .80 t or .802 t . All glottochronological calculations made hitherto are based on this formula (with the constant varying, as indicated, from .80 to .85). It is possible, however, to generalize from two to n languages. Suppose, to take the simplest case, that n is three. Call the languages A, B, and C. Then, after t millennia, the original vocabulary falls into 23, or eight parts. First, there is the vocabulary not found in any of the three languages. Let us call this the unrecoverable vocabulary . Then, we have the vocabulary surviving in A but not in B or C, in B but not in A or C, and in C but not in A or B. This vocabulary, which cannot be recovered by comparison, is the submerged vocabulary . The fifth, sixth, and seventh parts are the vocabulary surviving in two languages, that is, A and B, A and C, and B and C. Finally, as the eighth class, we will have the vocabulary surviving in all three languages, A, B, and C.

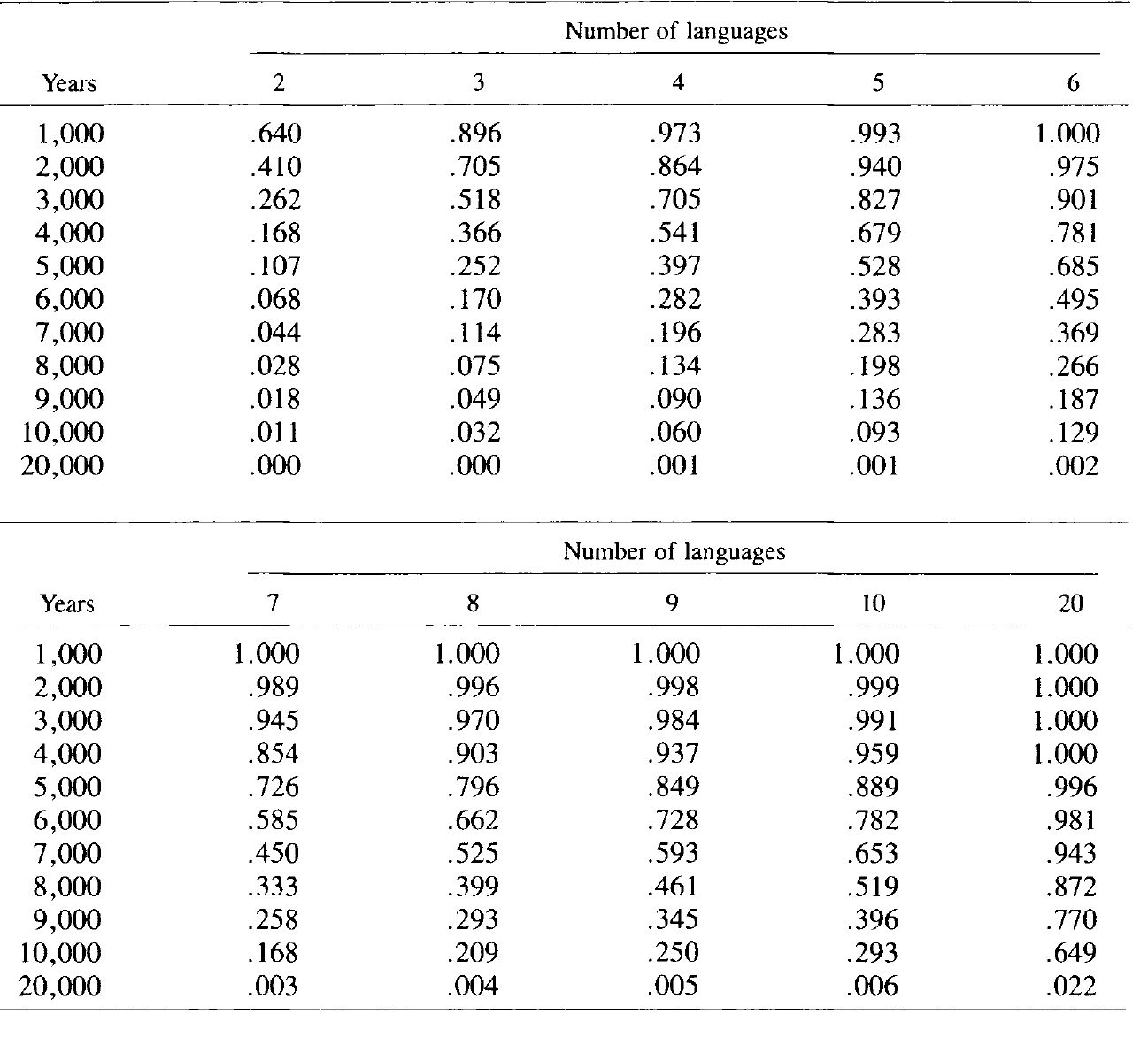

. Recoverable Vocabulary Based on the Joos Function

Note that the division of the original vocabulary into eight parts for n = 3 is

so that 1 + 3 + 3 + 1 = 8. But this is simply the well-known binomial expansion for the special case n = 3, for which the general formula is the following:

1 = p n + np n - 1 q + ( n /2) p n - 2 q 2 ... npq n - 1 + q n

. Recoverable Vocabulary Based on a Homogeneous Replacement Rate

If we take p as the retained vocabulary and q as the replaced vocabulary, then npq n - 1 represents the submerged vocabulary and q n the unrecoverable vocabulary. The vocabulary recoverable by comparison, then, is the total vocabulary minus the sum of the last two terms, i.e. 1 - ( npq n - 1 + q n ). Clearly, as the number of languages n increases, more and more of the lost vocabulary becomes merely submerged, and more and more submerged vocabulary becomes recoverable by survival in the additional languages.

Another relevant factor can be included in the calculation. We have assumed that all the items on the vocabulary list are equally stable. But this assumption is clearly improbable. If languages have been separated for, say, 5,000 years, what they still have in common will generally be the more stable elements. Hence a smaller proportion of items should be lost in the next 1,000 years than in the previous 1,000 years. In other words, we have a constantly decelerating rate of vocabulary loss. Failure to take this so-called dregs effect into account results in an underestimation of the retention rate.

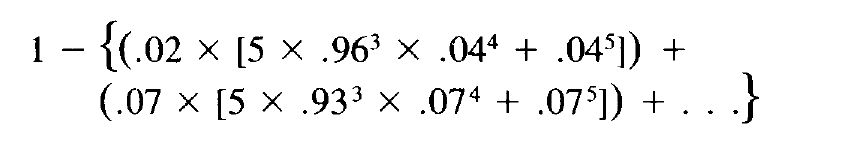

A proposal to deal with the dregs effect is found in Joos (1964). The proposal is to split the standard list into eight sublists according to a normal frequency distribution. The empirically ascertained rate of .80 for 1,000 years is then the sum of 2 percent of the list with r (retention rate) = .96; 7 percent with r = .93; 17 percent with r = .89; 24 percent with r = .84; 24 percent with r = .78; 17 percent with r = .71; 7 percent with r = .63; and 2 percent with r = .54.

The binomial theorem can be combined with the Joos function into a function that takes account of both variables, the number of languages, n , and the time in millennia, t . To illustrate, I give the first two terms of the function for five languages after 3,000 years (i.e. n = 5, t = 3):

, the expected proportion of recoverable vocabulary without compensating for the dregs effect is calculated for purposes of comparison.

The term mathematics of subgrouping is here restricted to the lexicon and is based on glottochronological assumptions. The model is in a sense a purely formal one, in which we investigate the consequences of extending the glottochronological model to more than two languages. Both the usual homogeneous retention rate of .80 per 1,000 years and the more complex, but empirically much more realistic, inhomogeneous retention rate proposed by Joos (described in Appendix A) are employed. The comparison shows that the clarity of evidence bearing on subgrouping problems varies both with the specific subgrouping and with the time period involved.

For this purpose, the four-language case has been investigated in considerable detail. Four appeared to be the minimum number needed to provide some insight into the problems involved without the use of an elaborate program on a large computer. But the general approach is promising, I think, and should be extended to more complex cases.

For reasons to be set forth in the final section, the method illustrated here is being advocated not as a practical way to carry out subgrouping even relatively small numbers of languages, but rather as an explanation of how and why certain difficulties arise. Furthermore, it will indicate how those difficulties can to some degree be overcome in practice through methods that transcend the limitations of glottochronology, at least under the usual assumptions.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Language in the Americas»

Look at similar books to Language in the Americas. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Language in the Americas and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.