1.1 Introduction

The gastro-intestinal tract presents all imaging methods with well-known technical challenges, including physiological motion (e.g. swallowing, gastric, and small bowel peristalsis) (Kellow ); the complexity, inaccessibility, and variability of the tubular anatomical components; the simultaneous intralu-minal juxtaposition of gas, solids, and liquids; and the presence of extrinsic motion related to blood flow and respiration. The disease processes that develop in the human GI tract create further imaging challenges as the disease patterns and morphology vary. The imaging may need to be optimised to demonstrate predominantly intra-luminal (e.g. polyps), mural (e.g. wall inflammation, tumor or stricture) or extramural (e.g. fistula formation, endometriosis, adjacent organ tumors) disease changes depending on the clinical presentation and the region of the tract under investigation. During the last century, X-ray-based imaging successfully addressed these challenges with a range of strategies that have become routinely practised techniques in hospitals worldwide. These include the use of bowel preparation methods, oral and tube delivered contrast media, the use of static and fluoroscopic (dynamic) imaging along with postural changes often aided by tilting examination tables.

Given these challenges, it is no surprise that the gastro-intestinal tract is one of the last body systems to be successfully imaged by MRI. This is partly due to the technical capability and limitations of MRI as well as the competing performance of other X-ray-based imaging modalities, including most recently developed multidetector CT. During the 1990s, improvements in MR hardware led to a substantial improvement in the ability to image the GI tract and this has now been demonstrated successfully on a wide variety of MRI systems. The majority of research developments and clinical applications have used 1.5 T 5060 cm diameter closed cylindrical bore systems. These provide a good compromise of field strength, related artifacts, volume coverage, and gradient performance. Higher field strength systems have also been used successfully but present a range of additional challenges, addressed in more detail in Chap. 2. This chapter will focus on the technical requirements and strategies that have been developed for supporting high-quality MR imaging of the GI tract. In this application as in most others, MR image quality is a compromise of many factors, not the least of them being the spatial and temporal resolution, both of which must be exploited for imaging the GI tract.

1.2 Coils

1.2.1 Requirements

Receiver coils are an integral part of MRI and for GI tract imaging the major requirements are for adequate volume coverage, RF homogeneity, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). In an ideal MRI system, all the imaging would be obtained using the body coil built into the cylindrical bore of the system, but in practice, although this usually provides good homogeneity and volume coverage, it provides inadequate SNR on both 1.5 T and 3 T systems. This results in compromised image quality and it is well known that inadequate SNR will also degrade contrast to noise ratio (CNR) which is often crucial for diagnosis (Constable and Henkelman ) that cover the abdomen and pelvis (e.g. 4044 cm cranio-caudally), essential for imaging the whole of the large and small bowel efficiently.

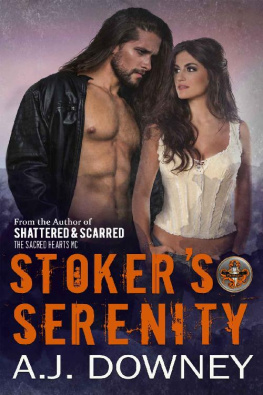

Fig. 1.1.

A typical flexible multi-element receiver array with sufficient superiorinferior coverage for the whole abdomen and pelvis

1.2.2 MultiCoil Receive Arrays

At the time of writing, most commercial body receive arrays comprising between 8 and 16 coil elements with separate or multiplexed receiver channels. Thirty-two channel arrays are becoming available commercially, but it is not yet clear whether the use of 64 and 128 channel arrays will offer gains that justify the complexity, cost, and increased risk of mechanical failure. In general, increasing channel and coil number creates problems in achieving adequate radiofrequency depth penetration but brings the benefit of facilitating parallel imaging reconstruction techniques. These techniques partially replace phase encoding with spatial sensitivity encoding related to the coil geometry. This can improve temporal resolution and reduce some artifacts but parallel receive acceleration reduces the SNR and is therefore probably most usefully exploited for optimizing imaging on higher field systems (3 T and above). The use of acceleration in two directions simultaneously facilitates more rapid 3D imaging, but at the present time it has not been possible to achieve 3D imaging with adequate spatial resolution and volume coverage in the subsecond range needed to freeze bowel peristalsis. The two main early methods utilize the spatial sensitivity information to create the replaced phase encode information slightly differently. Sensitivity encoding (SENSE) applies this information in image space after the Fourier reconstruction of K space (Pruessmann et al. ) performs this step within K space before Fourier reconstruction.

Another challenge for parallel techniques for bowel imaging is the requirement for calibration images to generate the spatial sensitivity maps. The early implementations acquired these calibration images separately at the beginning of an examination but for GI tract imaging subsequent signal variations owing to contrast medium and bowel motion could invalidate these images creating artifacts in the reconstruction process. More recently, self- or auto-calibrating techniques have been developed that are more appropriate for imaging the GI tract (Griswold et al. ).