Table of Contents

Guide

ALSO BY MATTHEW CARR

Fortress Europe: Dispatches from a Gated Continent

Shermans Ghosts: Soldiers, Civilians, and the American Way of War

Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain

The Infernal Machine: A History of Terrorism

2018 by Matthew Carr

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2018

Distributed by Two Rivers Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-428-5 (ebook)

CIP data is available.

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

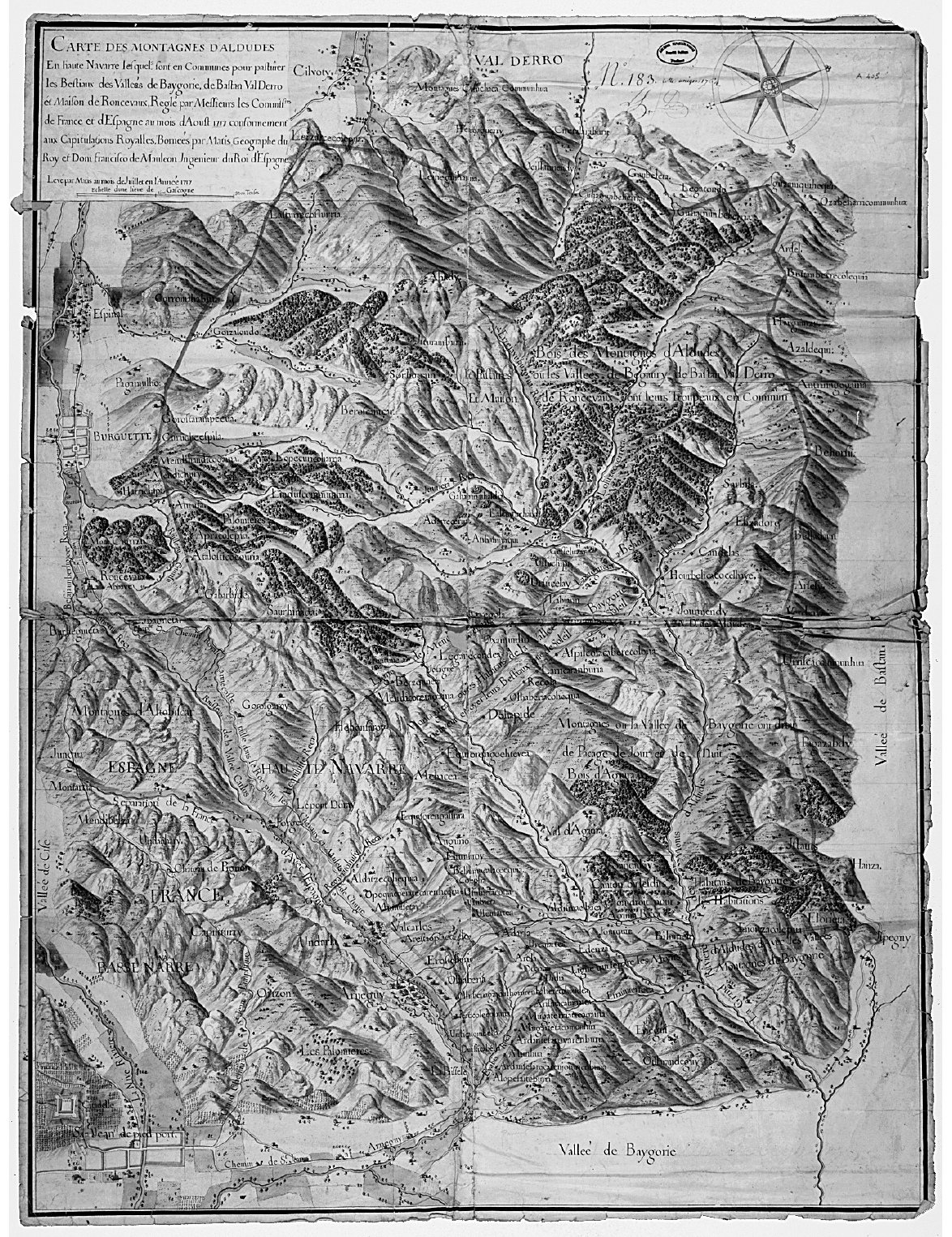

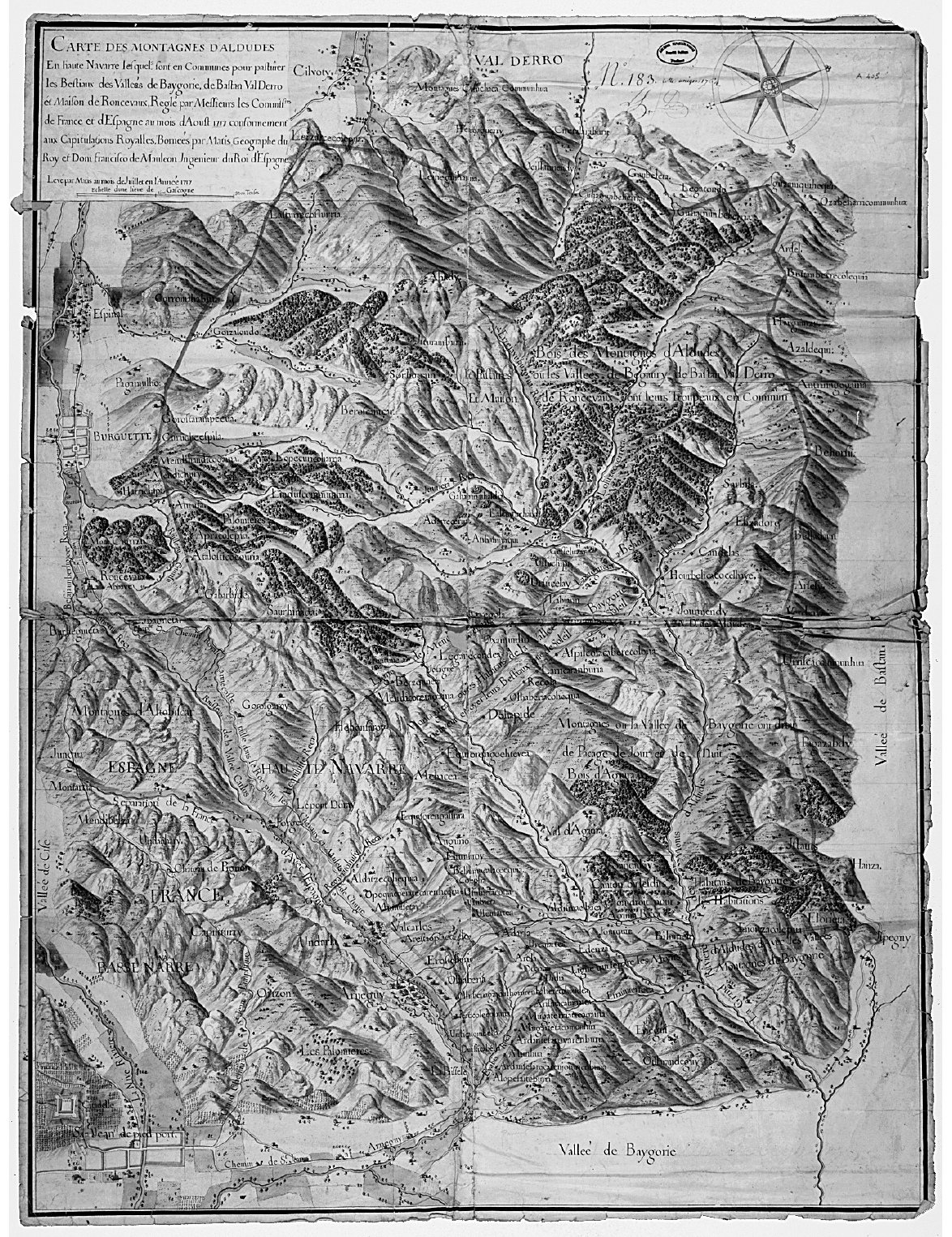

Map on page xi courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

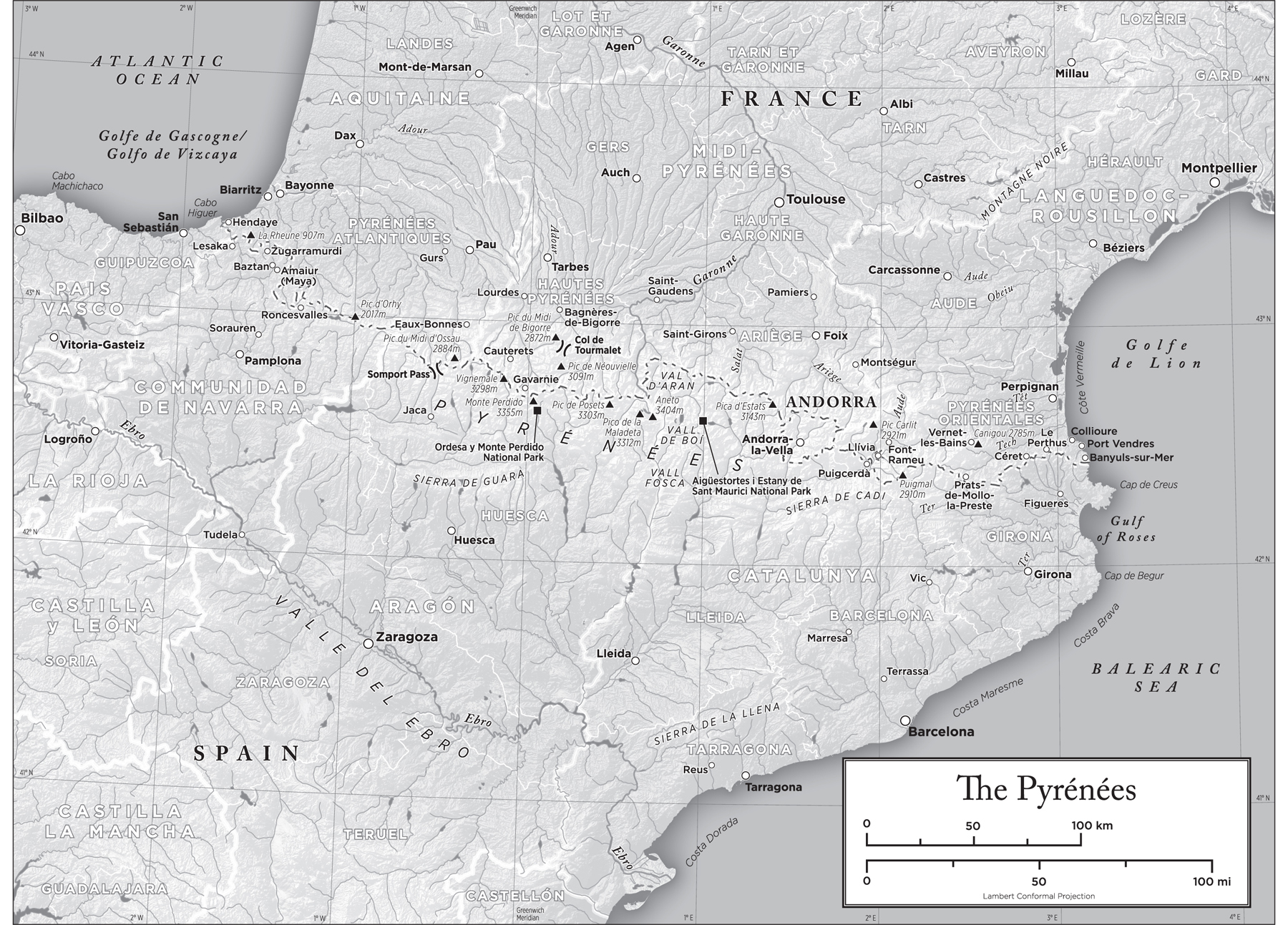

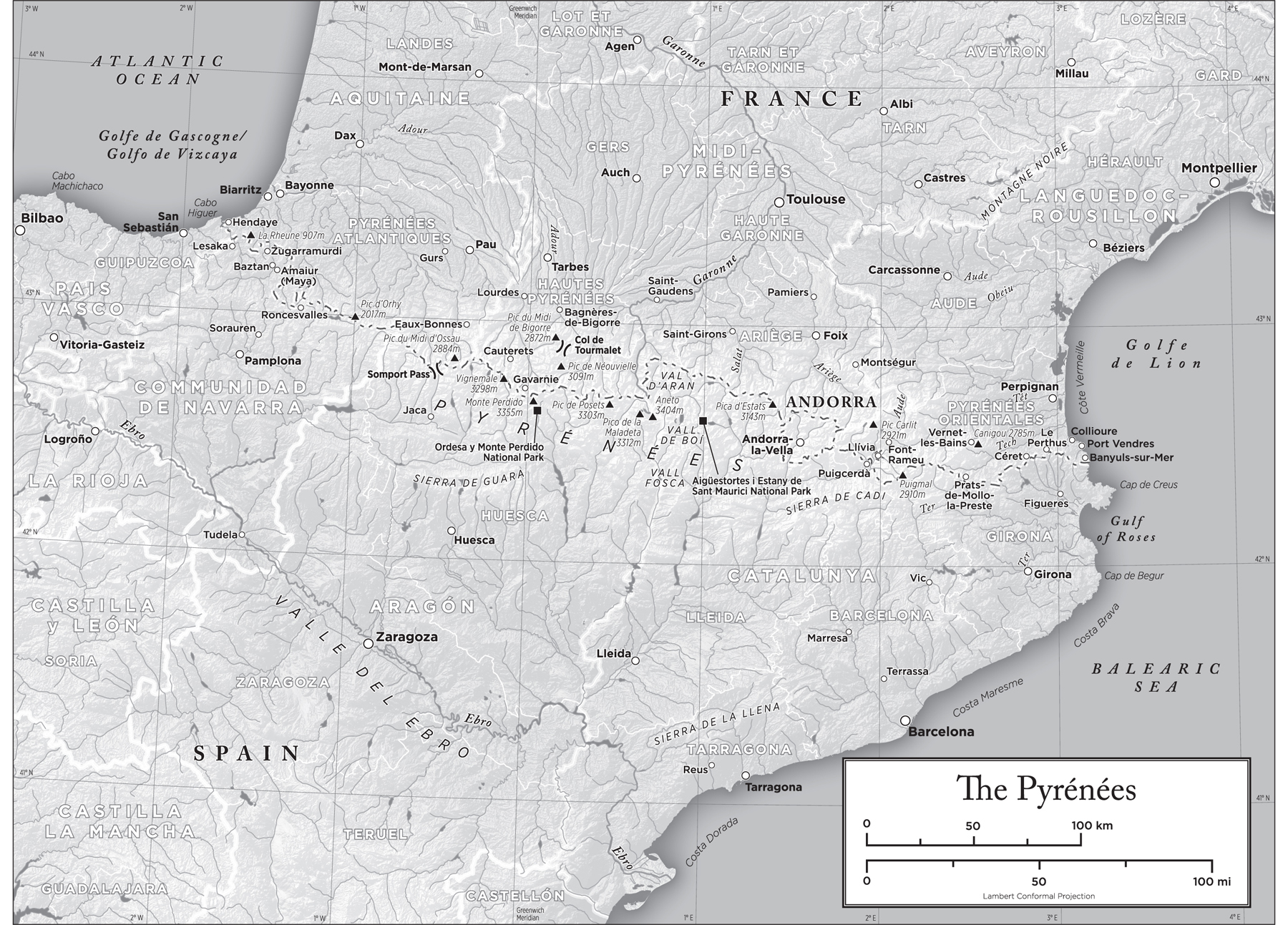

Map on pages xii and xiii by Nick Trotter

Composition by Westchester Publishing Services

This book was set in Adobe Caslon Pro

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Contents

Few books are written without the help of others. I want to thank Marta Marn Brviz, the indefatigable local historian of Hecho, Aragon, for providing me with copies of her excellent magazine Subordn, and for many other useful tips and suggestions. The late Scott Goodall (19352016) went beyond the call of duty to facilitate my participation in the Chemin de la Libert. Michael Richardson from the Art Space Gallery was extremely helpful in introducing me to Ray Atkinss work. Thanks also to Steve Waters, Andreu Jen, and so many others who shared these mountain trails with me and contributed to this book in ways that they may not even be aware of.

As always, much love to my wife Jane and my daughter Lara, who accompanied me on various Pyrenean jaunts. The anonymous narrator of Chris Markers film Sans Soleil once described three Icelandic children playing on a volcanic beach as the image of happiness. For me, the sight of the Bious pasturelands in 2016when I walked with Jane and Lara through a Pyrenean wonderland of mountains, forest, water, and animalswill remain indelibly imprinted on my mind as an image of happiness and perfection on earth, and there are no two people I would rather have shared it with.

We are not among those who have ideas only between books, stimulated by booksour habit is to think outdoors, walking, jumping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains or right by the sea where even the paths become thoughtful.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science

At 2,969 feet (905 meters), the Pyrenean mountain known as La Rhune in French and Larrun in Basque is not, in theory, a particularly formidable physical challenge compared with the 10,000-foot (3,000-meter) peaks that proliferate in the Central Pyrenees. Its shaven, cone-like peak straddles the French-Spanish border at the point where the Atlantic Pyrenees begin to rise from the flat coastal strip, giving onto Navarre to the south and the French Basque province of Labourd to the north. For hikers undertaking the trans-Pyrenean trail from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, La Rhune is a mere stepping-stone to the higher mountains farther west. It can easily be walked up and down in half a day, and French and Spanish families regularly do this most weekends.

Thousands of day-trippers also take the funicular railway, the Petit Train de La Rhune, which leads up to the summit from the Col de Saint-Ignace on the French side. Some go for a meal in the caf-restaurant on the summit, to take some exercise, and to enjoy a mountain view. Others are attracted by La Rhunes esoteric history as a sacred mountain. Its slopes are littered with Neolithic dolmens, and the summit was once associated with magic, sorcery, and akelarresthe Basque term for witches sabbathsin the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As late as the eighteenth century, a monk lived permanently on the summit to keep the forces of darkness at bay.

Nowadays the constant stream of visitors makes such a vigil redundant. I hiked up the sacred mountain with my wife and daughter in August 2015, on the hottest day of what was then the hottest summer on record. Despite La Rhunes relatively modest height, the steep gradient and the scorching heat made the climb much harder than I had expected. We were soon wilting as we trudged slowly up the stony path beneath a flawless blue sky, past beige Pyrenean cattle and little groups of short-legged wild Pottok ponies. La Rhune was once covered in forest, but most of its trees have long since been stripped to clear the way for pastureland or provide wood for the French and Spanish navies. A few isolated vestiges still remain, and about halfway up the mountain we stopped to have lunch in a copse of tall pines. A handful of Pottoks were also taking shelter there, standing stock-still with that stolid patience and innocence that Walt Whitman once observed in animals.

On seeing us eat, some of them ambled slowly toward us and nuzzled hopefully at our rucksacks. It has not been long since these beautiful animals were hunted to near extinction in order to make salami, and their luminous brown eyes were difficult to refuse. As we shared some of our picnic with them, I looked back down toward the sea and the blue sky and I felt one of those moments of euphoria that I have often felt in the Pyreneesa sense of having momentarily stepped out of the turbulent waters of twenty-first-century history and reconnected with a mountain world that was timelessly serene and benignly reassuring. The sensation was so pleasant that I was reluctant to step back out into the heat to continue our plodding progress toward the summit.

Soon the path grew significantly steeper, and we were surrounded by dozens of hikers walking up the curved track or clambering more directly over the slabs of rock that lay half-buried in the earth like giant stepping-stones. By the time we reached the summit, my daughter and I were red-faced and dehydrated, and we gorged on sugary soft drinks in the overcrowded visitors complex while we waited for my wife to join us. Whatever La Rhune had been in the past, there was nothing sacred about the complex of restaurants, cafs, and souvenir shops that covered the summit. Below the picnicking families and walkers we could see the funicular, crawling caterpillar-like up and around the sharp stony ridge above La Petite Rhunethe Lesser Rhuneand the darker blue of the Atlantic down below to the west. To our east, the razor-backed peaks of the Pyrenees disappeared in a blue haze that led all the way to the Mediterranean some 270 miles (435 kilometers) away.

Next page