What a trifling difference must often determine which shall survive, and which perish!

O ur hunger has shaped the earth in much the way that the hunger of a caterpillar remakes a leaf.

Thirteen thousand years ago, each of our ancestors consumed hundreds of different kinds of plants and animals in a week. Like wild chimpanzees and rats, they ate what could be found. Diets varied with the seasons. One berry in June, another in July. One insect when the rivers ran deep, other insects when they were dry. The species chosen also varied among cultures and regions. If you knew what a person was eating for dinner you could probably figure out what time of year it was and where that person was living. Not anymore.

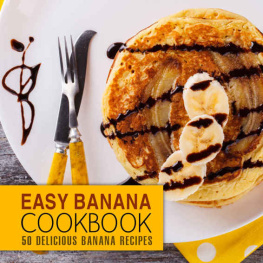

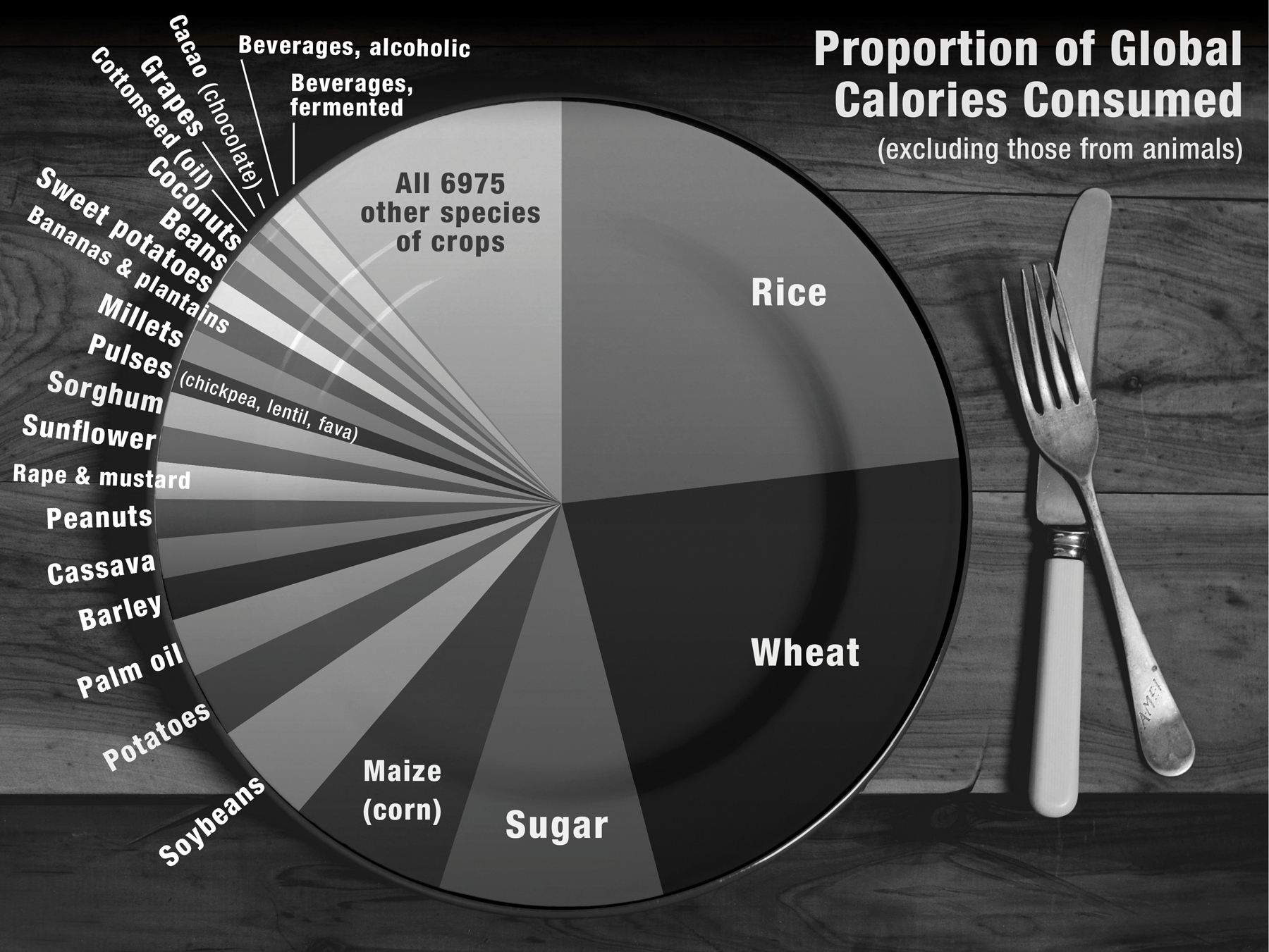

With the spread of agriculture, the diversity of foods consumed globally was reduced. With the globalization of agriculture, it was reduced further and homogenizedmade the same from one place to another. Humans now subsist on a declining diversity of foods. In 2016, the supply of calories to humans around the world was less diverse than it had ever been. Scientists have named and studied more than three hundred thousand living plant species. Yet 80 percent of the calories consumed by humans came from just twelve species and 90 percent from fifteen species. Our dependence on these foods has simplified the landscape of the earth. There are now more acres of corn than acres of wild grassland.

Biodiversity provides the richness of life: a richness in species, ways of living, flavors, aromas, and attributes. What we now face is the opposite of biodiversitya state of extreme monotony that is putting us at risk. Consider the banana.

Figure 1. Proportion of global plant-based calories consumed by humans as a function of various plant sources. Sugar is derived from multiple plant sources, including sugar beets and sugarcane. The vast majority of domesticated plant species play a very small role on the global plate. Data are drawn from Colin K. Khoury, et al., Increasing Homogeneity in Global Food Supplies and the Implications for Food Security, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, no. 11 (March 18, 2014): 40016.

O n a plate, a single banana seems whimsicalyellow and sweet, contained in its own easy-to-open peel. It is a charming breakfast luxury as silly as it is delicious and ever-present. Yet when you eat a banana the flavor on your tongue has complex roots, equal parts sweetness and tragedy.

In 1950, most bananas were exported from Central America. Guatemala in particular was a key piece of a vast empire of banana plantations run by the American-owned United Fruit Company. United Fruit Company paid Guatemalas government modest sums in exchange for land. With the land, United Fruit planted bananas and then did as it pleased. It exercised absolute control not only over what workers did but also over how and where they lived. In addition, it controlled transportation, constructing, for example, the first railway in the country, one that was designed to be as useless as possible for the people of Guatemala and as useful as possible for transporting bananas. The companys profits were immense. In 1950, its revenues were twice the gross domestic product of the entire country of Guatemala. Yet while the United Fruit Company invested greatly in its ability to move bananas, little was invested in understanding the biology of bananas themselves.

United Fruit and the rest of the banana industry did what industries do. They figured out how to do one thing wellin this case, grow one variety of banana, the Gros Michel. Moreover, because it is difficult to get domesticated bananas to have sex (they are puritan in their proclivities, blessed with virtually no seeds), the Gros Michel was reproduced via suckers, clonally.No banana was ever the wrong size, the wrong flavor, the wrong anything.

It is hard to overestimate how unusual the situation of bananas in the middle of the last century wasunusual not just in the history of humanity but also in the history of life. There is a patch of aspen trees in the Wasatch Mountains of Utah that many argue is the largest living organism on earth. It comprises some thirty-seven thousand trees, each of which is genetically the same as the other, and the argument goes that the trees, collectively, represent a single organism because they are identical and connected by their roots. But requiring pieces of an organism to be connected in order to be considered part of a collective is arbitrary. The ants in an ant colony, for example, are clearly part of the colony, even when theyre not physically in the nest. All this is to say that an argument can be made that large groups of genetically identical plants, even if not connected, may reasonably be considered a single organism. If one makes such an argument, the banana plantations of Central America in the 1950s were not only the largest collective organism alive at that point, they also may well have been the largest collective organism ever to live.

Economically, growing just a single clone of bananas was genius. Biologically, it posed problems. These problems had already been noted, for example, in the British production and export of coffee in the 1800s. At that time, the British drank coffee, not tea. They drank coffee exported from their colony Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Early on in Ceylon, coffee plantations were planted among wild forests.real affluencebanks, roads, hotels, and luxury. It was an unbridled success, or seemed to be.

Harry Marshall Ward, a British fungal biologist visiting Ceylon in 1887, warned farmers that farming such large plantations of a single variety of coffee would cause problems. Pests and pathogens, once they arrived in the plantations, would devour them. This was, he thought, particularly true of coffee rust, which was already present in Ceylon, but it would also be true of any other pest or pathogen that arrived. Nothing would stop such an organism from quickly devouring all the trees, since they were all of the same varietyand thus equally susceptible to whatever threat might arise or arriveand planted very close together. This is exactly what happened. Coffee rust wiped out the coffee of Ceylon and, subsequently, much of the rest of the coffee of Asia and Africa. Coffee growers replanted with tea.