The writing of this book has been a lengthy process, but I was greatly aided by the generous assistance of a number of individuals and institutions. I must begin by thanking Professor Hew Strachan, first as my PhD supervisor and now as series editor, for his invaluable advice and criticism throughout. I have benefited from his unrivalled knowledge of the First World War and Africa, as well as his generosity in providing extended access to rare and hard to obtain books. Professor Brian Holden-Reid and Dr Simon Ball provided valuable comments on my dissertation that have helped in this book.

Dr Kent Fedorowich directed me to a number of unexpected and valuable primary sources as well as reading portions of the manuscript. He has shared his expertise in Imperial politics and South Africa to my considerable advantage. Lieutenant Colonel Ian van der Waag has been of great assistance in tracking down South African sources, providing valuable insights into the Union Defence Force and its members. I must also thank him for allowing me to present my ideas at two conferences.

I would also like to thank Ms Ann Crichton-Harris and Mr Andrew Kerr for their continued interest and assistance in my work. Mr Gerald Rilling placed his extensive knowledge of East Africa at my disposal in addition to tracking down a wide variety of books on the subject. Despite the pressures of her own PhD studies, Ms Alexandra Luce kindly undertook research on my behalf in Lisbon and provided a great deal of useful material in translation.

The help provided by the staff of a number of libraries and repositories has been invaluable to my researches. In the United Kingdom I would like to thank the University of Glasgow and Library; the British Library; the National Archives (formerly the Public Record Office); the Imperial War Museum; the National Army Museum; the Bodleian and Rhodes House Libraries, University of Oxford; the Cambridge University Library; the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, Kings College, London; the Wiltshire Record Office; Regimental Headquarters, the Queens Lancashire Regiment; Regimental Headquarters, the Staffordshire Regiment; and the Royal Engineers Corps Library.

Overseas, I have been greatly assisted by the staff of the Bundesarchiv and the Geheimes Staatsarchiv, Preuischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin; the Bundesarchiv-Militrarchiv, Freiburg im Breisgau; the Muse Royal de lArme, Brussels; the Arquivo Ministrio dos Negcios Estrangerios and Arquivo Histrico Militar, Lisbon; the Documentation Centre, South African National Defence Force and South African National Archives, Pretoria.

I am particularly grateful to the Documentation Centre of the South African National Defence Force and the Muse Royal de lArme for allowing me to reproduce photographs from their collections. Crown copyright material is reproduced with the permission of Her Majestys Stationery Controller.

Thanks are also due to my publisher, Jonathan Reeve, and the staff at Tempus for their work in bringing this book to print. Finally, I must again thank my family for their long-standing support and encouragement. Without them, this book could not have been written.

Contents

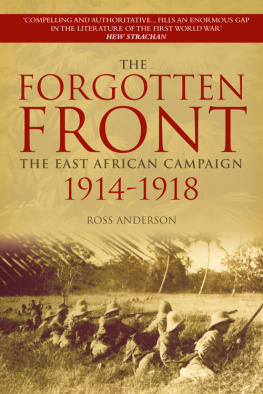

The First World War continues to fascinate historians and readers alike. The industrialisation of warfare brought the trenches, mass mobilisation and huge casualty lists. This gave rise to a long-lasting and spirited debate about its origins, conduct and consequences that remains very much alive today. Perhaps it was the sheer scale of effort, and resulting sacrifices, coloured by differing national outlooks that keeps it so controversial. In the English speaking world, study has largely focused on the Western Front with lesser consideration given to Gallipoli and Palestine. The other, more peripheral theatres have received a fraction of the attention. In proportion to the level of effort, this may be understandable, but in historical terms it represents a gap.

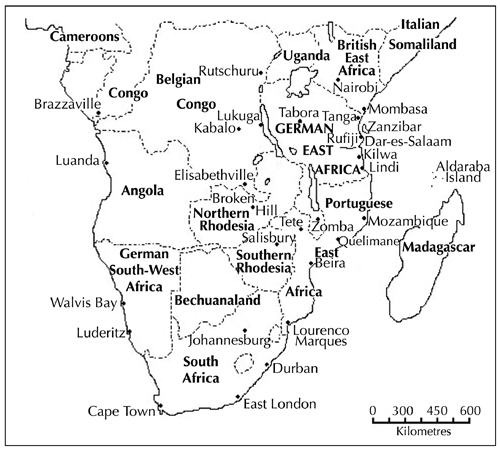

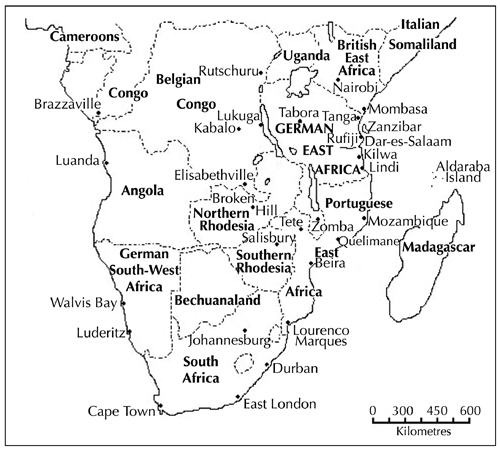

This is particularly true of the East African campaign that lasted from August 1914 until November 1918, with the fighting stopping two days after the armistice in Europe. It was never of first importance, yet it ranged from the modern states of Kenya and Uganda in the north, through the Congo, Ruanda, Burundi, and Tanzania in the centre, to Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique in the south. Few inhabitants, European or African, escaped its effects or ravages, while the colonial empires were irrevocably changed by the conflict. If it was insignificant in global terms, the war there was of overwhelming local consequence.

East Africa has not been entirely ignored, as a number of official histories, memoirs and regimental journals were published in the post-war years. Much of the modern view of the campaign has been shaped by two personal accounts written forty years apart. The most important of the two came from the pen of the undefeated German commander, Generalmajor Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck in his My Reminiscences of East Africa. This interesting and entertaining memoir provided an insight into British operations of the period as well as criticising senior officers and many units harshly. However, Meinertzhagen remains a controversial figure and his account is based on his personal diaries and not as a history of the campaign.

The official British history did not appear until 1941 and only one volume out of two was ever published:Volume One of the History of the Great War: Military Operations East Africa. This was published in 1959 and was based on a draft manuscript taken from the now destroyed official documents and maps. Furthermore, the author had had extensive exchanges with the British official historians up until September 1939. Unfortunately, with copies being scarce and written in German, it has been relatively little used.

A number of popular accounts appeared in the 1960s with another batch in the 1980s. While colourful and interesting, only one made use of Die Operationen and none conducted any archival research.

Since the opening of the British First World War records in the mid-1960s, there has been an enormous amount of primary material available. To this may be added records in the South African National Defence Force Documentation Directorate and the South African National Archives as well as that of the Belgian Muse Royal de lArme. There is also much in Portugal and Germany, notably the very substantial Lettow and Boell papers in the Bundesarchiv/Militrarchiv in Freiburg, as well as the vast quantities of non-military departmental papers in Berlin. In fact, the amount of material available is beyond the capacity of one person to read.

This book tries to employ new material in an attempt to gain a fuller understanding of the fighting and operational aspects of the East African campaign. It deals with the background to the conflict, the political goals that drove it, the forces involved and the manner in which they fought it. It attempts to produce a balanced view of the differing perspectives as well as judgements of performance, national aims and the means of fulfilling them. It is a story of imperial conflict and its telling reflects its records. However, one important voice is largely silent; that of the Africans who were drawn into the war by their colonial masters. Written records rarely reflect their point of view, yet without them few of the events described could ever have occurred. Silence must not be confused with lack of importance and the African contribution to the campaign was absolutely essential, if far from fully explained. This work cannot possibly hope to cover all aspects of the war nor give all equal prominence as it was simply too vast. I hope that it will stimulate interest and encourage others to study its many aspects.

Next page