T he best doctors in the world are Doctor Diet, Doctor Quiet, and Doctor Merryman. Jonathan Swift | Food for the Body, Fuel for the Brain |

A s recently as World War II, scientists as well as the general public considered diet to have little or no influence on mental functioning. Research over the last 40 years, however, has revealed a close relationship between diet and the brainso much so, in fact, that trendy brain bars are popping up that specialize in juices and foods considered to improve mentation, or mental activity. It is becoming clearer that our brain influences what and how we eat, and that what and how we eat influences our brain. This chapter identifies various specific findings in this arena of the food-brain connection.

Two primary chemical actors head the complex cast of characters in the tense drama of appetite control: chemicals that trigger hunger and chemicals that trigger satiety. If these are in good order, much of the rest of ones chemical makeup will have a minimal effect on appetite and weight control. Significant discoveries have come on the scene in the last five years, and huge pharmaceutical product development research efforts currently focus on finding acceptable exogenous (externally administered) ways to optimize a persons hunger-satiety balance. Current estimates based on twin studies consider the genetic influence on weight to be extremely higharound 6070 percent. Combined with the meager 5 percent success rate of diets, this paints a bleak picture for the role of self-control in weight management. Authorities suggest that wed be better off changing the environment than trying to change the individual. Do we hear a movement afoot to abolish faux food? New York City Mayor Bloomberg has done his part by successfully promoting a ban on the sale of sugary drinks larger than 16 ounces in restaurants and concession stands. (Wait, this just in: a judge has blocked his honors ban. Watch for developments!) The environmentalists formed the Sierra Club. How about the Fiber Club for the nutritionists?

Chemicals That Signal Hunger

Sarah Leibowitz, a neurobiologist at Rockefeller University in New York City, has identified the area of the brain in which this drama plays out: the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus (see appendix A). Chemical players that trigger appetite include galanin (discovered by Leibowitz, this is a neuropeptide that craves fat), norepinephrine, neuropeptide Y, and cortisol. In addition, a research team led by Masashi Yanigasawa at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas reported the discovery of two hormones that send a hunger message ( Cell, February 20, 1998). Yanigasawa calls these hormones orexin-A and orexin-B. The orexins have their own receptor network in the hunger section of the hypothalamus and have been found to send an extremely strong hunger signal in mice. Development is under way for use with humans as both a stimulant and a suppressant of appetite.

Another hormone related to weight is ghrelin : it makes people hungry, slows metabolism, and slows the ability to burn fat. It is highest before meals, lowest just after. Unfortunately, those who lose significant amounts of weight tend to produce more ghrelin, so it apparently serves evolutionarily as a defense against starvation. Persons injected with ghrelin report feeling hungrier and, if exposed to a buffet with a large quantity and variety of food, will eat 30 percent more than they typically would consume.

University of California, Irvine, College of Medicine researchers have identified the receptor for melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH), a key ingredient in the appetite control process. Earlier research discovered that MCH influences how often and how much rats and humans eat: the more of the hormone, the stronger the appetite. The Irvine research team, headed by pharmacology professor Olivier Civelli and senior pharmacology researchers Hans-Peter Nothacker and Yumiko Saito, located the receptors that bind with MCH in the hypothalamus, olfactory area, and the nucleus accumbens, all involved in one way or another in smell, taste, and feeding urges. Research is under way to clarify these processes and how they might be brought under control for the benefit of the masses desiring and needing to be less massive.

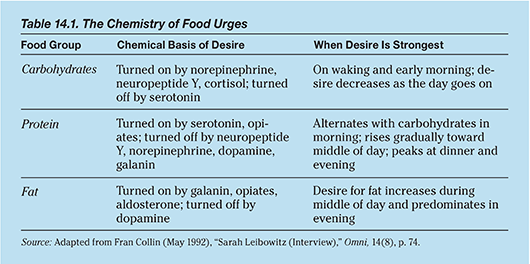

Sarah Leibowitz has identified the chemical sources of urges for specific food groups, as well as the time of day during which the urges are strongest (Collin, 1992, p. 74). A summary is shown in table 14.1.

At a spring 1998 meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine in New Orleans, Yale University researchers reported that high levels of cortisol are associated with high cravings for fatty snacks. When given a choice, high-cortisol snackers head for the nachos, low-cortisol snackers for lower-fat snacks. Cortisol levels are increased by stressful experiences.

Chemicals That Signal Satiety

Chemical players that shut down appetite include enterostatin (produced by the stomach and pancreas in response to the ingestion of fat), serotonin, dopamine, cholecystokinin (CCK), and leptin (from the Greek leptos, thin), a protein produced by the newly discovered obesity gene on chromosome 6. After youve eaten, cholecystokinin is released in the intestines to tell the brain youre full. Leptin tells the body whether to burn fat youre eating or store it as fat. GlaxoSmithKline is developing a synthetic version of cholecystokinin, with exciting early results. Regeneron is developing a synthetic version of leptin to tell the body that it has enough stored fat and its time to burn all calories. Houstons M. D. Anderson Cancer Center has developed a chemical that melts fat cells in mice by attacking the proteins in blood vessels that feed their fat cells. But all is not well in leptin land. Sanofi of Paris developed rimonabant, a wonder drug that made one feel full, reduced triglycerides, increased good cholesterol, and restored sensitivity to insulin. In 2008, 56 countries were actively prescribing it when the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) declared the risks to outweigh the benefits. Sanofi suspended the drug, and the EMEA withdrew its approval of rimonabant in 2009.

Food is more than physical nourishmentit forms the basis of bonding between mother and child and, according to recent research, between friends. Eating sets off two (at least) processes: oxytocin and cholecystokinin are released to the brain. Weve known for a while that oxytocin was released during maternal nursing (and during sexual orgasm in both sexes, and in nest building, and in uterine contraction during childbirth, and in response to massage), thus helping to cement the bond between mother and child. But we now know that nursing and eating in general not only set off oxytocin, but also cholecystokinin, the latter of which sends a message from the intestine to the brain that says, Food has now gotten where it needed to! Thanks, system, youre working just fine. But Kerstin Uvnas-Moberg of Swedens Karolinska Institute has discovered that when oxytocin and cholecystokinin are blocked, a suckling lamb will not bond with its mother. Both messengers must be active for bonding to take place. Thus we understand why business partners, sales reps and their prospects, and friends in general like to do lunch. Therefrom comes bonding, and the cooperative, pleasurable mood with which it is associated. If food be the music of bonding, munch on, together. Ones associates shall be known by ones table mates.

David York, of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University, learned that enterostatin shuts off the pleasure system of the brain (see topic 31.6), which is activated in ecstasy as a response to fat consumption. Fat loses its appeal when enterostatin levels are sufficiently high. Low galanin levels are associated with low fat intake and high galanin levels with high fat intake, unless enterostatin levels are also high, when fat intake will be limited (because fat satiety is reached quicker). If enterostatin levels are low, then fat satiety will be delayed, unless galanin is also low, when little fat will be ingested. More recently, Stephen Bloom, an endocrinologist at the Imperial College in London, announced in Nature the discovery of a suppressor similar to enterostatin named GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1), whose receptors are located in the hypothalamus.

Next page