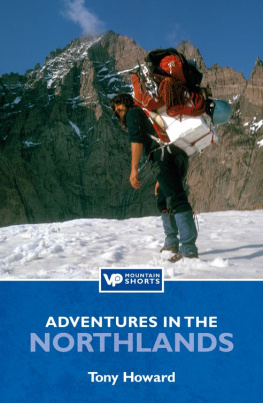

To my mum and dad; my sister, Kathryn; my daughter, Tannith; Di Taylor, my ever-undaunted companion on many years of exploration, and now my wife; and all those who unquestioningly supported me along the way.

Thanks.

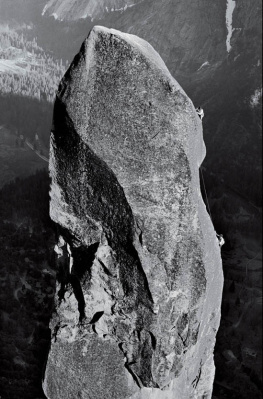

I had never intended to write my autobiography; a bit too narcissistic perhaps, or an admission that its game over. I even held publication of Troll Wall in abeyance until 2011 forty-six years after simultaneous first ascents by a Norwegian team and us, the English. I had written the story directly after the climb then shelved it to escape the limelight and get on with my life.

When it was finally published, people asked when I was going to write my autobiography. Matt Heason, for example, says in his review of the book that, the chapters either side of the ascent are absolutely fascinating. I sincerely hope that he is, as I write, locked in a room somewhere typing up his full memoirs as they are destined to impress and inspire. In similar vein, Andy Kirkpatrick commented, Youd hope that age would slow Tony enough so that hed finally sit still and write a few more memoirs, so we might have a chance of more books like this.

Then in 2014, despite it being a good summer, events transpired to ground me more than anticipated. My regular climbing mate Mick Shaw was struggling with a bad heel after smashing it in a bouldering fall. My shoulder was also playing up Wear and tear, what do you expect at your age?, the doctor said unhelpfully and my wife and climbing and trekking partner, Di, had a knee problem. Why dont you do some writing? she suggested.

I do enjoy writing, so here I am: shut up in a room, sat at my computer while out of my window I can see the Peak District cliffs where I started climbing over sixty years ago. Di and I are still out every week, either walking or climbing. We had our annual six-week trip to Jordan in the spring and together with friends almost finalised one of our oldest ongoing projects, the 400-mile Jordan Trail. We were also walking and climbing in Shetland, even new routing on a sea cliff we found, and we will be out in Jordan for another six weeks in the autumn, hopefully putting the finishing touches to the trail.

I finally decided that writing up my stories might serve a purpose, in that it will hopefully entertain or be of interest. But more that it might inspire someone, somewhere, to live their dreams and escape the pre-ordained path of life that others may expect of them just as I did. Though maybe having adventures was easier in my day. We were lucky. The climbing world was largely unexplored even the cliffs surrounding my Peak District home were little known.

Since then the world has changed beyond imagination: we had no TVs, computers, mobile phones or GPS. No one we knew flew anywhere; travel was infinitely more difficult, as was gathering information on what were then considered remote destinations. Even maps were often hard to come by. But my motto was always: you never know until you go.

Places like Norways Lofoten Islands were well off the beaten track, as was Morocco; no one had climbed in Tafraout when we went there in 1964 after a winter ascent of Jebel Toubkal and we were the first Brits to climb in the Taghia canyons in 1980. Now these places are easily accessible for climbing holidays in the sun. More amazingly, the now world-famous mountains of Wadi Rum in Jordan were also unknown other than in the writings of T.E. Lawrence until we traced his footsteps in 1984 and were welcomed by the Bedouin. And as recently as 2002 we were told that we were the first foreigners to report the existence of the Living Bridges of Meghalaya, and the following year to visit a Naga village on Mount Saramati on the India-Burma border, then a closed area.

Everywhere we went we were welcomed by the indigenous people, whose hospitality was always overwhelming. In particular the tribal peoples of Africa and the Middle East, the Qashqai and Kurds of Iran, the Tahltan up in the Yukon, the Greenland Inuit, the many and varied Malagasy, Sudanese and Ethiopian tribes, the Sherpas of Nepal and the Nagas and Bodos in the jungles of north-east India all of whom had so little to give but gave so much. I owe the richness of my experiences to them and to my friends who accompanied me on these adventures to the worlds wild places, and also to those of my family that I left behind but nonetheless accepted my idiosyncrasies. I hope this book will be some small repayment.

Meanwhile, as I have been writing this, Di has just reminded me that the sun is out. She has changed her mind.

You can write again later, she said. We should be out on the hills.

Shes right.

Tony Howard

Greenfield, September 2018

I belonged to that generation which saw, by chance, the end of a thousand years life.

Cider with Rosie, Laurie Lee

The day I was born was a momentous day. Mum and Dad must have wondered anxiously about the world I was entering. It was Britains darkest hour: the eve of the World War Two Dunkirk evacuation in May 1940. Over 7,000 men were rescued from the beaches of northern France on that first day, and over a third of a million on subsequent days. I, of course, knew nothing of it, but soon after my father was sent to work in London at the time of the Blitz, which lasted from September 1940 to May 1941. Bombs fell on London for seventy-six consecutive nights, killing over 20,000 civilians and destroying more than a million houses. Worrying days for Mum, though Dad wrote often and whenever possible came home to Greenfield, the village where we lived on the edge of the Pennine moors in the West Riding of Yorkshire.

Rationing of food and petrol was introduced the year I was born and continued throughout the war. Bread escaped rationing but was in such short supply that it had to be sold a day old when it would be going stale and could consequently be cut into thinner slices. The shortage of food was so great that on my fifth birthday three weeks after the end of the war in Europe in 1945 food rations were reduced even further. The weekly bacon allowance went down from four ounces to three ounces, cooking fat from two ounces to just one, and the meagre meat ration of 1/2 d (half an old penny) per family had to be taken in corned beef. Supplies of food continued to be so short that bread was finally added to the ration list a year later and was not removed until 1948.

Rationing of other foods continued until 1954 when I was fourteen and the last item, meat, was finally taken off the governments list. Mum used to make rag puddings to make the meat go further. They consisted of chopped-up pieces of meat with onions and gravy, wrapped in suet pastry, tied in a rag and boiled in a pan on the fire. Cheap, and saved electricity too. Raiding our pantry to make a swift treacle butty when no one was around, or sticking my finger in the jam jar, became habits. Mum never said anything. Dripping butties were another secret delight, the best bits of dripping being the dark brown bottom layer. Mum always knew I had been in the jar as the top crust had to be broken to get at the juicier layer underneath.

My sister Kathryn was born a couple of years after me, and with Dad still working away, Mum worked hard bringing us up. Despite the difficulties of life at that time, our home was a happy place, surrounded on three sides by fields. It seemed everyone knew everyone in the village. Nestled beneath the western edge of the Pennines, Greenfield is overlooked by the wild moors and jutting gritstone crags of Chew Valley. These cliff-rimmed hills which I still think are the nearest thing to mountains between Snowdonia and the Lakes were to become my childhood playground and had a huge influence on my life, but not before my formative years in the friendly warmth of the village community.