Contents

About the Author

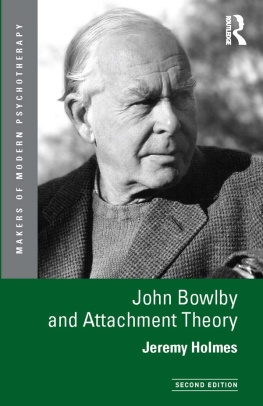

John Bowlby (1907 1990) was educated at the University of Cambridge and University College Hospital, London. After qualifying in medicine, he specialised in child psychiatry and psychoanalysis. In 1946 he joined the staff of the Tavistock Clinic where his research and influential publications contributed to far-reaching changes in the ways children are treated and to radically new thinking about the social and emotional development of human beings.

He held honorary degrees from the Universities of Cambridge and Leicester and received awards from professional and scientific bodies, including the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the British Paediatric Association, the Society for Research in Child Development, the American Psychological Association and the New York Academy of Medicine.

To Three Friends

Evan Durbin

Eric Trist

Robert Hinde

Separation

Anxiety and Anger

Attachment and Loss

Volume 2

John Bowlby

Preface

In the preface to the first volume of this work I describe the circumstances in which it was begun. Clinical experience of disturbed children, research into their family backgrounds, and an opportunity, in 1950, to read the literature and to discuss problems of mental health with colleagues in several countries led me, in a report commissioned by the World Health Organization, to formulate a principle: What is believed to be essential for mental health is that the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate and continuous relationship with his mother (or permanent mother-substitute) in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment (Bowlby 1951). To support this conclusion evidence was presented for believing that many forms of psychoneurosis and character disorder are to be attributed either to deprivation of maternal care or to discontinuities in a childs relationship with his mother figure.

Though the contents of the report proved controversial at the time, most of the conclusions are now accepted. What has plainly been missing, however, is an account of the processes through which the many and varied ill effects attributed to maternal deprivation or to discontinuities in the motherchild bond are brought into being. It is this gap that my colleagues and I have since striven to fill. In doing so we have adopted a research strategy that we believe is still too little exploited in the field of psychopathology.

In their day-to-day work, whether with disturbed children, disturbed adults, or disturbed families, clinicians have of necessity to view causal processes backwards, from the disturbance of today back to the events and conditions of yesterday. Though this method has yielded many valuable insights into possible pathogenic events and into the kinds of pathological process to which they appear to give rise, as a research method it has grave limitations. To complement it, a method regularly adopted in other branches of medical research is, having identified a possible pathogen, to study its effects prospectively. If the pathogen has been correctly identified and the studies of its effects in the short and long term are skilfully executed, it then becomes possible to describe the processes set in train by the pathogenic agent and also the ways by which they lead to the various consequent conditions. In such studies attention must be paid not only to the processes set in train by the pathogen but also to the very many conditions, internal and external to the organism, that affect their course. Only then can some grasp be had of the particular processes, conditions, and sequences that lead from a potentially pathogenic occurrence to the particular types of disturbance with which the clinician was in the first place concerned.

In adopting a prospective research strategy my colleagues and I early became deeply impressed by the observations of our colleague, James Robertson, who had recorded, both on paper and on film, how young children in their second and third years of life respond while away from home and cared for instead in a strange place by a succession of unfamiliar people, and also how they respond during and after return home to mother (Robertson 1952; 1953; Robertson and Bowlby 1952). During the period away, perhaps in residential nursery or hospital ward, a young child is usually acutely distressed for a time and is not easily comforted. After his return home he is likely to be either emotionally detached from his mother or else intensely clinging; as a rule a period of detachment, either brief or long depending mainly on length of separation, precedes a period during which he becomes strongly demanding of his mothers presence. Should a child then come to believe, for any reason, that there is risk of a further separation he is likely to become acutely anxious.

Reflecting on these observations we concluded that loss of mother figure, either by itself or in combination with other variables yet to be clearly identified, is capable of generating responses and processes that are of the greatest interest to psychopathology. Our reason for this belief was that the responses and processes observed seemed to be the same as those found to be active in older individuals who are still disturbed by separations they have suffered in early life. These comprise, on the one hand, a tendency to make intensely strong demands on others and to be anxious and angry when they are not met, a condition common in individuals labelled neurotic; and, on the other, a blockage in the capacity to make deep relationships, such as is present in affectionless and psychopathic personalities.

From the start an important and controversial issue has been the part played in the responses of children to separation from mother by variables other than that of separation per se; these include illness, the strange surroundings in which a child finds himself, the kind of substitute care he receives while away, the kind of relations he has both before and after the event. It is plain that these factors can greatly intensify, or in some cases mitigate, a childs responses. Yet evidence is convincing that presence or absence of mother figure is itself a condition of the greatest significance in determining a childs emotional state. The issue is already discussed in Chapter 2 of the first volume, where a description is given of some of the relevant findings, and is taken up again in the first chapter of this one, where attention is given to the results of a foster-care project undertaken in recent years by James and Joyce Robertson in which they sought to create a separation situation from which many of the factors that complicate institutional studies were eliminated; and in which the emotional needs of the children would be met as far as possible by a fully available substitute mother (Robertson and Robertson 1971). Study of the Robertsons findings has led to some modification of views expressed in earlier publications, in which insufficient weight was given to the influence of skilled care from a familiar substitute.

In parallel with the empirical studies of my colleagues, I have myself been engaged in studying the theoretical and clinical implications of the data. In particular, I have been trying to sketch a schema able to comprehend data derived from a number of distinct sources:

(a) observations of how young children behave during periods when they are away from mother and after they return home to her;

(b) observations of how older subjects, children and adults, behave during and after a separation from a loved figure, or after a permanent loss;

Next page