Contents

Guide

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Brooks is an investigative journalist for Private Eye magazine. He writes on a range of subjects, including financial crime, public services and taxation. His work has appeared in many other outlets, including the Guardian and on the BBC. He was awarded the Paul Foot Award for Investigative Journalism in 2008 and 2015 and his work was highly commended in the 2016 British Journalism awards. He lives with his family in Reading.

Published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Richard Brooks, 2018

The moral right of Richard Brooks to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Image copyrights: figures Pressefoto ULMER/Markus Ulme

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 028 5

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 029 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 030 8

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Alex, Joe and Brigitte

CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

PROLOGUE

In the summer of 2015, seven years after the financial crisis and with no end in sight to the ensuing economic stagnation for millions of citizens, I visited a new club.

Nestled among the hedge-fund managers plying their trade from some of the worlds most expensive real estate on Grosvenor Street, Mayfair, No. 20 had recently been opened by accountancy firm KPMG. It was, said the firms then UK chairman Simon Collins in the fluent corporate-speak favoured by todays top accountants, a West End space for people to meet, mingle and touch down. Directors of client companies, who have lots of meetings, can often find it pretty lonely if they dont have a base. The cost of the fifteen-year lease on the five-storey building was undisclosed, but would have been many tens of millions of pounds. It was evidently a price worth paying to look after the right people.

Inside, No. 20 is patrolled by a small army of attractive, sharply uniformed serving staff. On one floor are dining rooms and cabinets stocked with fine wines that would cost three-figure prices in a restaurant. On another, a cocktail bar leads out onto a roof terrace. Gazing down on the refreshed executives are neo-pop-art portraits of the men whose initials form todays KPMG: Piet Klynveld (an early twentieth-century Amsterdam accountant), William Barclay Peat and James Marwick (Victorian Scottish accountants) and Reinhard Goerdeler (a German concentration-camp survivor who built his countrys leading accountancy firm).

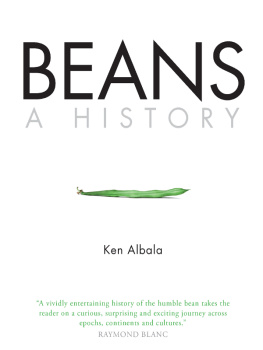

Figure 1: The cocktail bar at No. 20, KPMGs new club in Mayfair, with portraits of Piet Klynveld, William Barclay Peat, James Marwick and Reinhard Goerdeler.

KPMGs founders had made their names forging a worldwide profession charged with accounting for business. Theyd been the watchdogs of capitalism who had exposed its excesses. Their twenty-first-century successors, by contrast, had been found badly wanting. They had allowed a series of US subprime mortgage companies to fuel the financial crisis from which the world was still reeling, and had offered unqualified endorsement of British bank HBOSs finances as it went to the wall. The opening of No. 20 was a revealing move during what for any other industry would have been a crisis of confidence and reputation.

What do they say about hubris and nemesis? pondered the unconvinced insider who had taken me into the club. There was certainly hubris at No. 20. But by shaping the world in which they operate, the accountants have ensured that they are unlikely to face their own nemesis. As the world stumbles from one crisis to the next, its economy precarious and its core financial markets inadequately reformed, it wont be the accountants who pay the price of their failure to hold capitalism to account. It will once again be the millions who lose their jobs and their livelihoods. Such is the triumph of the bean counters.

INTRODUCTION

MEET THE BEAN COUNTERS

I lower refreshed eyes to the two white pages on which my careful numbers transcribe the company balance sheet. And, smiling to myself, I remember that life, which contains these pages, some blank, others ruled or written on, with their names of textiles and sums of money, also includes the great navigators, the great saints, poets of every era, none of whom appear on any balance sheet, being the vast offspring cast out by those who decide what is and isnt valuable in this world.

So reflected Bernardo Soares, the 1920s Lisbon bookkeeper who narrates Fernando Pessoas Book of Disquiet, lamenting his modest crafts inability to capture the splendour of life.

It is true that accounting dwells on the business of life transactions, assets, liabilities and profits rather than the joy of it. But in doing so, the practice that has become a byword for tedious employment plays a central role in creating the environment in which commerce and culture can thrive.

Accounting even gave the world the written word. While the early societies of Mesopotamia could pass on their stories well enough through word of mouth, they could not rely on it for recording the activities that characterized the dawn of civilization: the sharing and trading of produce rather than its immediate consumption. Bean counters, who really did count beans, needed to write things down. It was the pictographic scripts representing quantities of grain, sheep and cattle stored, written on wet clay using a cut reed, that would be adapted to produce shapes representing sounds, and from there written words.

For centuries, accounting itself remained a fairly rudimentary process of enabling the powerful and the landed to keep tabs on those managing their estates. The word derives from the French aconter, to account for money or other assets with which one has been entrusted. But as the first part of this book explores, that narrow task has been transformed by commerce. In the process it has spawned a multi-billion-dollar industry and lifestyles for its leading practitioners that could hardly be more at odds with the image of a humble number-cruncher. The 4m-a-year, fifty-something recent UK boss of the second largest global accountancy firm, PricewaterhouseCoopers, drives the same Aston Martin model as James Bond (though, in his case, with a licence to bill). Next time you peer into a flashy car wondering if its being driven by a film star, youre more likely to find yourself gawping at a bean counter.