For my oldest son

Ali Raphael Kattan-Wright

one hot kid

The Harvard Common Press

535 Albany Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02118

www.harvardcommonpress.com

Copyright 2005 by Clifford A. Wright

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or

retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wright, Clifford A.

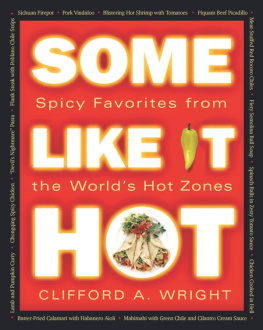

Some like it hot : spicy favorites from the world's hot zones / Clifford A.

Wright.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-55832-268-X (hc. : alk. paper) ISBN 1-55832-269-8 (pbk. : alk.

paper)

1. Cookery (Spices) 2. Cookery, International. 3. Spices. I. Title.

TX819.A1W75 2005

6341.6'383dc22

2005004953

ISBN-13: 978-1-55832-268-4 (hardcover); 978-1-55832-269-1 (paperback)

ISBN-10: 1-55832-268-X (hardcover); 1-55832-269-8 (paperback)

Special bulk-order discounts are available on this and other Harvard

Common Press books. Companies and organizations may purchase books

for premiums or resale, or may arrange a custom edition, by contacting the

Marketing Director at the address above.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cover recipe: Shredded Shrimp and Serrano Chile Tacos,

Cover photograph 2005 Nina Gallant

Cover design by Night & Day Design

Interior design by Richard Oriolo

Illustrations by Paul Hoffman

Acknowledgments

I can't imagine having written this book without the Internet and people from around the world to help me. Although there is a cast of hundreds behind this book, besides individuals mentioned in the recipes themselves, I would also like to thank Taoufik Ben Azouz and Sofia Azouz, Neelam Batra, Rick Bayless, Gene Bourg, Unjoo Lee Byars, Cayobo, Bonnie Lee, Youssouf Mariko, Thomas Payne, Sarah Pillsbury, Nattera Roajphlastien, Martha Rose Shulman, Su-Mei Yu, and Dawn Zain for their help on culinary matters. Most of the recipes in this book were consumed by myself, Sarah Pillsbury, and my son Seri Kattan-Wright, who now understands the expression "chile burns twice."

I would also like to thank my agent, Doe Coover, and at The Harvard Common Press, my editors, Pam Hoenig and Valerie Cimino; managing editor Christine Corcoran Cox; production editor Abby Collier; copyeditor Ann Cahn; and, on the marketing side of things, Skye Stewart and publicist Liza Beth. Finally, I would like to thank my publisher, Bruce Shaw, for Some Like It Hot.

Introduction

The World of Spice

Our eyes nearly popped out of our heads when my daughter Dyala and I saw our Chongqing Spicy Chicken arrive. The platter was covered with hundreds of red chiles. I don't think I'm exaggerating, although we didn't actually count them. We were slightly alarmed, but game. The other diners in this San Francisco restaurant were gringos, and they whispered as they rubbernecked toward our table. It was clear to us that this dish was not on the menu and that we had successfully communicated to our Chinese waitress that we might look like Americans, but our culinary souls were Sichuan. The platter sat in front of us for a while because we weren't sure whether we were supposed to attack it or cleverly dodge the chiles like a soldier ducking withering fire. We decided to eat, slowly, and with chopsticks, picking around the chiles. It was amazing! The chicken knucklesthat's what I called themwere actually a section of the wing and so tender that you could eat the delicate bones as well. The flavor was intense, very intense, and delicious, very delicious, and hot, very hot. We started sweating and continued eating, quietly, without a word to each other. We ate all of it and looked up, sniffling, and Dyala said, "That was incredible, Dad. Do you really think you can re-create it?" I must, I responded, because I must have this again. Well, this book has Chongqing Spicy Chicken () and 300 other amazingly hot recipes from what I call the "Hot Zone," the spiciest, hottest cuisines in the world.

No, I'm not a masochist and I'm not a chile-head. I have simply become fascinated with the cuisines around the world that are so piquant. Why do some people love spicy food so much? And why do others abhor it? I brought to this book a lot of assumptions about very spicy food, and in the course of several years of research and recipe testing, almost all of them evaporated and a whole new world opened up. This is the world I hope to bring to you. It is a new world of taste, and, appropriately, the story begins in the New World.

How It All Began

WHEN I WAS A CHILD, I learned that Columbus discovered America after sailing the ocean blue. Over the course of a lifetime I've learned that there is a lot more to Columbus besides the man and his famous voyage. There is "the Columbian exchange," a reference to the exchange between the Old and New Worlds. Plants were exchanged in both directions and so were animals. But the "exchange" refers to much more than that because the Old World also brought pestilence, guns, and science to the New World.

The horticultural transference from the Old World to the New and the New to the Old really begins with the second voyage of Columbus, when he returned to Hispaniola with 17 ships, 1,200 men, and seeds and cuttings for the planting of wheat, chickpeas, melons, onions, radishes, salad greens, grapevines, sugarcane, and fruit stones for the founding of orchards.

From a culinary point of view, arguably the most important thing that came about from Columbus's discovery of America is the chile. That might seem non-sensical when we think of beans or tomatoes. Or what about the potato, you may protest, which played a huge economic role in countries from Ireland to India? Ah, yes, the potatobut I said culinary, not economic. The chile changed the world as much as the potato did. In culinary terms, it provided gustatory heat, or spiciness, far beyond the hottest spice known until then, black pepper. In economic terms, it's possible the chile contributed to killing off the absurdly profitable spice trade that had existed between the Indo-Malaysian archipelago and Europe for two millennia. (In the reverse direction, of the most important foods brought to the New World from the Old there are many to choose from, but one would have to agree with Alfred W. Crosby, Jr. in his The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492 [Greenwood Press, 1972], that it all began with sugar.)

Some like it hot, and those who do live within a globe-encircling band between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricornmore or less. Here in this area some call the Hot Zone, a temperate to tropical climate lends itself to a cuisine that is blisteringly hot, where people enjoy fiery hot foods spiked with chiles and spices that dance in your mouth. Whether it's the moles of Mexico or the kimchi of Korea or the curries of India or the piri-piri of Africa, this is a world cuisine of very exciting food that has captivated the American palate. One can dream up all kinds of adjectives to describe this cuisine from the Hot Zone: hot, zesty, jazzy, furious, blistering, electrifying, incendiary, piquant, pungent, lustful, sensual, sultry, torrid. It's all that and more, because these cuisines are delicious, too.

There is an interesting phenomenon about this spicy zone, this Hot Zone: it cannot be entirely described in geographic terms because, contrary to popular thought and contrary to the first sentence of the previous paragraph, it is not exclusively centered in the Tropics or around the equator. High in the cold Andes, or in the highlands of Mexico City, or on the frigid Korean peninsula, people are eating some very spicy-hot food. The chile, the hottest spice, may also be the oldest spice, as it seems to have been used by humans as early as 7000 B.C. It traveled well and was readily accepted elsewhere, probably because it had attractive and appetizing-looking fruits produced in a short period of time and because it yielded fruit year round in most climates where it thrived. There was another benefit, too: the fruits could be dried for storage or transport and used later. Because of its pungency, a little chile went a long way, and that must have been very attractive to poor people eating readily available bland, starchy foods.

Next page

![Goldstein Darra - Fiery Ferments [eBook - Biblioboard]: 70 Stimulating Recipes for Hot Sauces, Spicy Chutneys, Kimchis with Kick, and Other Blazing Fermented Condiments](/uploads/posts/book/201436/thumbs/goldstein-darra-fiery-ferments-ebook.jpg)