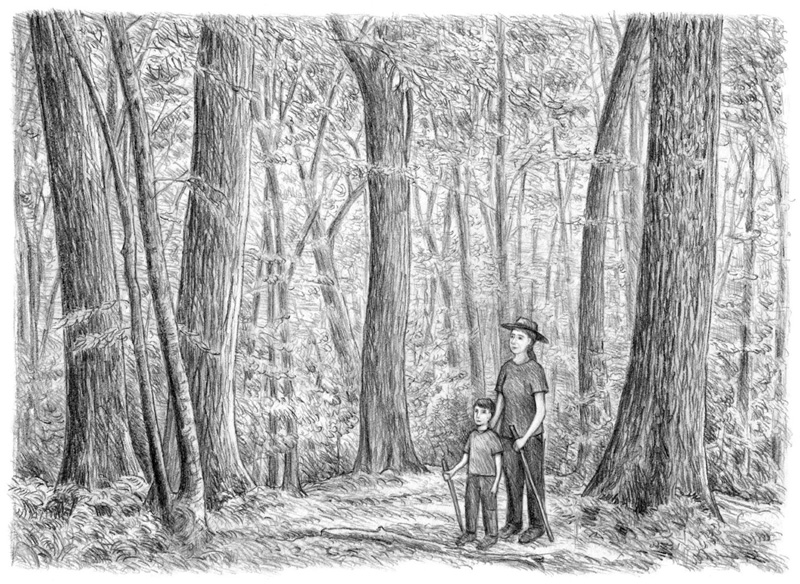

NATURES TEMPLES

The Complex World of Old-Growth Forests

Joan Maloof

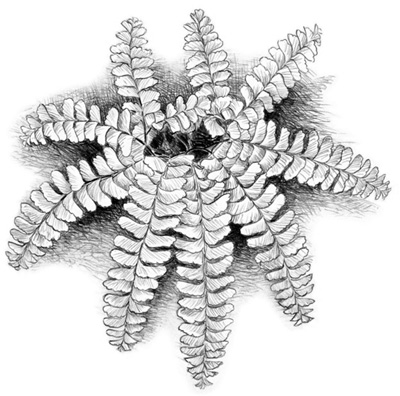

Illustrated by Andrew Joslin

Contents

Preface

FORESTS HAVE SPRUNG NATURALLY FROM THE EARTH WITH NO HELP required from humans. Although trees are the most obvious part of a forest, many, many other life forms exist there as well. The measure of this variety of life forms is termed biodiversity. The past ten thousand years have seen a drastic reduction in biodiversity due to human activities, primarily the way we manipulate the land. Many species have disappeared completely. Harvesting wood products from forests is one way that humans affect the land. In this book we look specifically at how the life forms in an ancient undisturbed forest, including the trees, differ from the life forms in a forest manipulated by humans. The details are shared in these pages, but I will give you the conclusion up front: more species exist in old-growth forests than in the forests we manage for wood products, and some species exist only in older forests.

In the chapters ahead you will frequently see old-growth forests compared to managed forests, so perhaps it is useful to clarify these terms right away. The forests that have formed naturally over a long period of time with little or no disturbance we call old-growth forests. In contrast, managed forests are the result of purposeful human action. Management techniques include logging, thinning, burning, planting, and spraying. Forests can be managed in many different ways and for many different reasons, but most often they are managed to grow timber for particular wood products that result in a financial return.

Although wood is a wonderful renewable resource, and most owners of forestland are now careful to replant after harvesting, it is a misconception that typical forest management can conserve all forest biodiversity. Scientific evidence tells us otherwise. In these pages I present the evidence. The studies that enable us to challenge the misconception are sprinkled far and wide among many different journals and over many years, so I thought it helpful to compile descriptions of the studies and their results in a book. I originally intended to include only the studies done in eastern North American forests (since the western forests have been the focus of other books), and although the focus here remains on eastern forests, I soon realized that including a global perspective added depth to the evidence.

Over and over I have read or heard espoused that forests must be managed to be healthy. Perhaps forests must be managed to get the healthiest economic return, but true biological health is found in the unmanaged old-growth forests. I can say that because the scientists who have done these careful studies have offered their data to us. I also know it to be true because I have spent time in many, many old-growth forests and have heard the birdsong, witnessed the soaring canopies, and breathed the forest air.

When we try to pick out anything by itself, John Muir wrote in My First Summer in the Sierra, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe. The truth of this often-quoted line will be evidenced over and over again in these pages. Although each chapter has a specific topic, you will soon see that they are all, indeed, hitched together.

Acknowledgments

MY DEEPEST THANKS GO TO THE GENEROUS AND PATIENT CONSULTANTS who have given their time to guide my efforts. I list them here in order of the topics they are associated with:

History of the forestWilliam Stein, Binghamton University, New York

The oldest treesNeil Pederson, Eastern Kentucky University

The largest treesRobert Leverett and Will Blozan, Eastern Native Tree Society

AmphibiansStephen Tilley, Smith College

SnailsDaniel Douglas, University of Tennessee

InsectsTim Schowalter, Louisiana State University Agricultural Center

Herbaceous plantsAlbert Meier, University of Georgia

Mosses and liverwortsGregory McGee, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse

FungiTimothy Baroni, State University of New York at Cortland

LichensSteven Selva, University of Maine at Fort Kent; and Eric Peterson

WormsTami Ransom, Salisbury University

MammalsCarolyn Mahan, Penn State Altoona; and Aaron Hogue, Salisbury University

This book began with the vision of collecting and publishing papers from various contributors. In response to my request for manuscripts a number of people generously contributed original papers: Marc Abrams, Timothy Baroni, Daniel Douglas, Robert Leverett, Carolyn Mahan, Tim Schowalter, Steven Selva, and Stephen Tilley. The style and scope of the book changed over time, but those papers were critically helpful. Any errors or opinions in these pages are completely mine, but many of the useful facts came from the others.

In 2014 I was awarded the Mary Byrd Davis Residency, which allowed me to spend a month working on this book at the Bordeneuve Retreat in the French Pyrenees. Retreat owner Noelle Thompson made sure I could write all day ensconced in divine solitude and be rewarded at days end with her marvelous food, wine, and companionship. Such a generous gift, and so personally meaningful, because the residency was endowed by Noelles uncle, Robert Davis. Bob, as I know him, was husband to the late Mary Byrd Davis, who edited Eastern Old-Growth Forests: Prospects for Rediscovery and Recovery (1996) and Old Growth Forests in the East: A Survey (2002). These publications are always within reach on my desk, and they have guided my work so often that I feel that this book is an extension of them. Her son, John Davis, has become a good friend. Together we continue speaking for the old-growth forests.

Concerned that old-growth forests are still falling, and inspired by the idea that we might allow future old-growth forests to recover, I created the Old-Growth Forest Network, a nonprofit organization. Deepest thanks to my board of directors for encouraging me to take time away from my executive director duties to complete this book. Particular thanks to Will Cook for assistance with editing. Thanks, also, to my loyal administrative assistant, Susan Barnett, for keeping the organization humming along while I was busy writing. Please visit our website, oldgrowthforest.net, to learn more about what we do. And a huge thanks to all our supporters. We are not just a network of forestswe are also a network of people who care about forests.

Finally, I wish to thank my extended tribe of family and friendsso many that I could not possibly name them all here. But if I had to pluck out a few names, I would extend special thanks to my daughter, Alyssa Maloof, who is the light of my life; to friend Tim Thompson, for keeping my beloved cat company during my long and frequent absences; and to Jamie Phillips for his companionship these past few years.

What is an old-growth forest?

WHAT IS AN OLD-GROWTH FOREST? WHAT DOES IT LOOK LIKE? HOW does it function? These questions seem straightforward, but no simple answer to any of them exists. There may never be a single, widely accepted definition of old growththere are just too many strong opinions from different perspectives including forest ecology, wildlife ecology, recreation, spirituality, economics, sociology, asserts Tom Spies, research forest ecologist for the Pacific Northwest Research Station of the U.S. Forest Service.