The "weather mark" identifies this book as having been planned & produced by John Weatherhill, Inc., 7 - 6-13, Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo / Book design, typography & layout by John Dower & Donald Bell / Composed by Kenkyusha / Plate making & printing by Kinmei / Binding by Makoto / The type face used is Monotype Garamond, with display in hand-set Garamond

CHAPTER ONE

Introducing T'ai-chi

Man cannot live fully without exercise. The I Ching (Book of Changes) says: "Nature is always in motion. Man also should strengthen himself without interruption." Exercise leads to robust health, high spirits, and rational thinking. There are, however, many kinds of exercise: ballplaying, swimming, traditional boxing, wrestling, and weightlifting, to name but a few. Without exception, each has built-in limitations. Weather restricts ballplaying, weakness prevents participation in the more rigorous sports, and age and sex inhibit activity in others. More importantly, though these sports differ in form, they are similar in that most never go beyond reliance on weight, force, and speed.

T'ai-chi is both an integrated exercise and an enjoyable sport for all: rich and poor, strong and weak, young and old, male and female. Weather does not inhibit its practice. Requirements of time and space are minimal. If one has a space approximately four feet on a side and can spare ten minutes a day, he can practice T'ai-chi without spending a cent.

For hundreds of years Westerners have been puzzled at seeing Chinese from all walks of life doing this effortless, rhythmical, ballet-like exercise both at dawn and at dusk. By way of explanation, Chinese say that whoever practices T'ai-chi, correctly and regularly, twice a day over a period of time will gain the pliability of a child, the health of a lumberjack, and the peace of mind of a sage. The amazing results achieved suggest that this is not just idle boasting, that perhaps, in some way unknown to Western science, T'ai-chi can indeed do all this, and more. Stressing slow respiration and balanced, relaxed postures, it certainly promotes deep breathing, digestion, the functioning of the internal organs, and blood circulation. And perhaps there is also basis for the claim that T'ai-chi can relieve, if not actually cure, neurasthenia, high blood pressure, anemia, tuberculosis, and many other maladies.

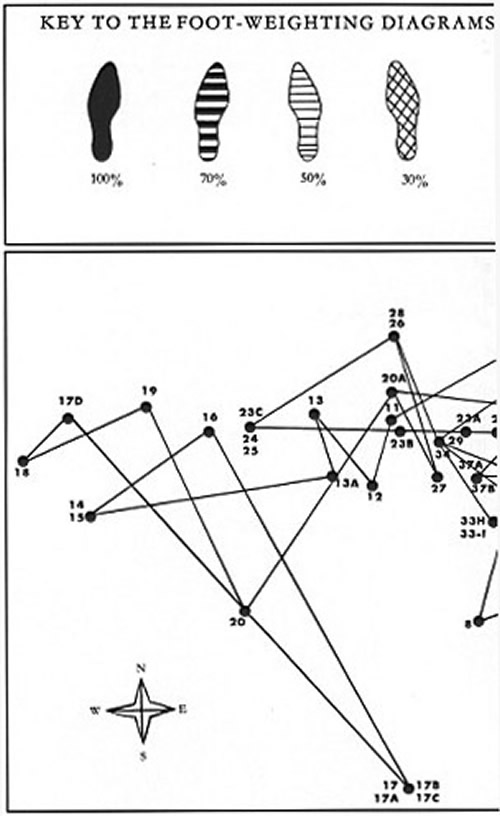

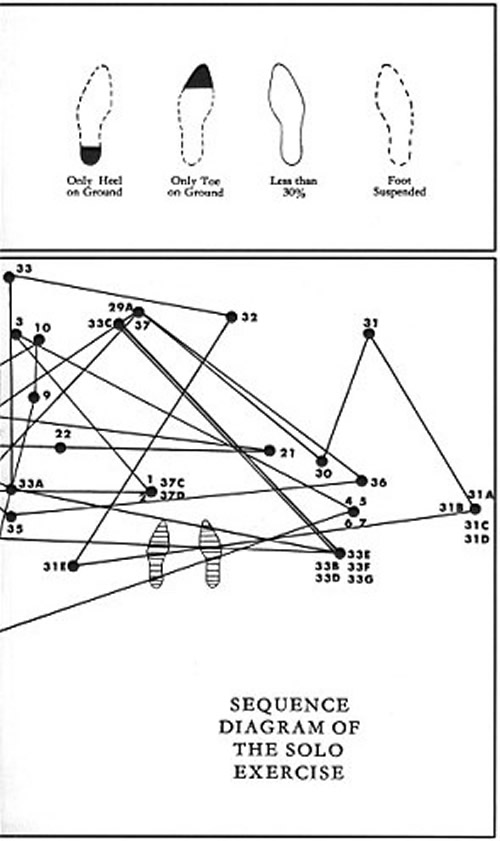

Besides the Solo Exercise (pages 12-77) with its therapeutic value, T'ai-chi also has two other aspects. The Pushing-Hands Practice (pages 80-89), in which two opponents compete in trying to uproot each other, constitutes a sport. Beyond this, T'ai-chi is a method of self-defense par excellence. Judo, Aikido, and a few other Asian methods stress the yielding principle of T'ai-chi, but none achieve to the same degree its relaxation, suppleness, and subtlety.

The Taoists advocate wu wei (non-action or effortlessness) and the Buddhists venerate "emptying." The motto for T'ai-chi practice must be "investment in loss." It is what Confucius meant by k'e chi to subdue the self. How is this manifested in mundane affairs? It means to yield to others, thus quashing obstinacy, egotism, and selfishness. But it is not an easy thing. To persist in the Solo Exercise amid life's busy requirements is self-humbling. In the Pushing-Hands Practice, the student must accept failure many times over in the early stages. To yield and adhere to an opponent cannot be achieved by an egotisthis ego will not tolerate the bruisings necessary before mastery comes. But here, as in life, this proximity to reality must overcome ego if one is to walk a whole man.

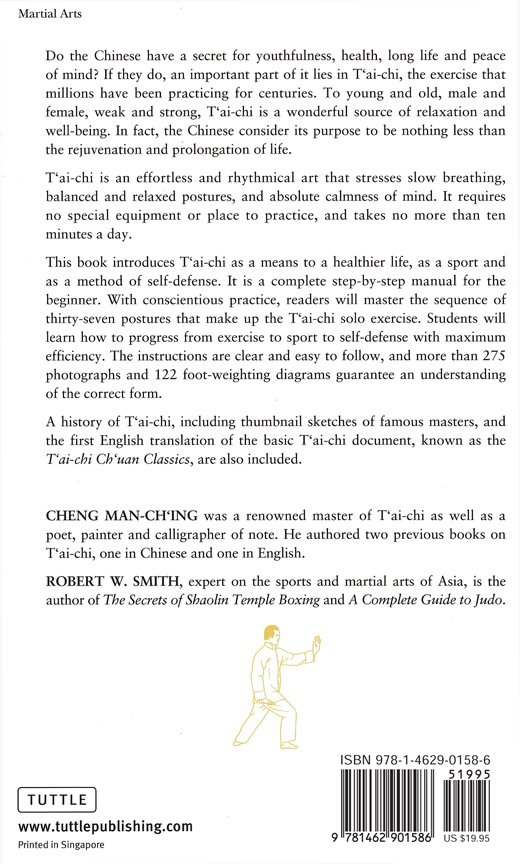

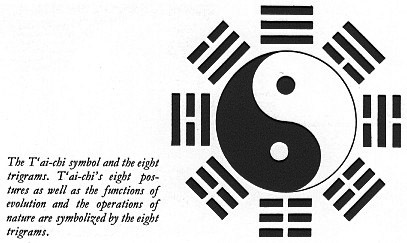

THE NAME The full and formal title is T'ai-chi Ch'uan (pronounced "tie-jee chwan,") the latter word meaning simply "fist" or "boxing." The term t'ai-chi is derived from a concept of Chinese philosophy meaning "supreme ultimate." Philosophically, T'ai-chi is said to be the primary principle of all things and is represented by a circle divided into light and dark aspects, representing the yang and yin concepts, which reflect opposite attributes such as male and female, activity and inactivity, firmness and softness, light and darkness, and positive and negative. Through the complementary interaction of yin and yang sprang the five elementsfire, water, earth, wood, and metal. This book is not the place to go into the intricacies of the subject. Suffice it to say that T'ai-chi was named for an ultimate philosophical principle because its early proponents felt it expressed an ultimate physical principle.

HISTORY There are four main theories on the origin of T'ai-chi. The most popular states that Chang San-feng, a Taoist priest of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), learned it in a dream. A second theory holds that it originated in the T'ang dynasty (618-907) and developed through four separate schools: the Hsu, Yu, Ch'eng, and Yin. A third claim states that the Ch'en family of Ch'en Chia Kou in Honan province created T'ai-chi during the Ming dynasty (1368-1654). The fourth thesisand the most reasonable simply avers that the founder is unknown, but that the development of T'ai-chi dates from one Wang Tsung-yueh of Shansi province, who introduced it in Honan during the reign of Ch'ien-lung (1736-95) of the Ch'ing dynasty. This last theory holds that once, while passing through Ch'en Chia Kou in Wen-hsien (Honan province), Wang Tsung-yueh saw the villagers practicing a form of hand boxing called pao cti ui . Later at his inn he made an offhand remark on the method, which the villagersalmost all surnamed Ch'en had practiced for generations. His remark brought several challenges and he met them all successfully. The villagers were impressed and asked Wang to stay for a short while to teach them his method. Moved by their sincerity, he agreed and helped them modify their hard boxing method into the softer T'ai-chi.