T HE P ENGUIN P RESS

N EW Y ORK

2007

Body of Work

Meditations on Mortality

from the Human Anatomy Lab

C HRISTINE M ONTROSS

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd. Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0745, Auckland, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd,

24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2007 by The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Christine Montross, 2007

All right reserved

The individual experiences recounted in this book are true.

However, in some instances, names and descriptive details have been altered to protect the identities of the persons involved.

Portions of this book first appeared in different form in Brown Medicine magazine.

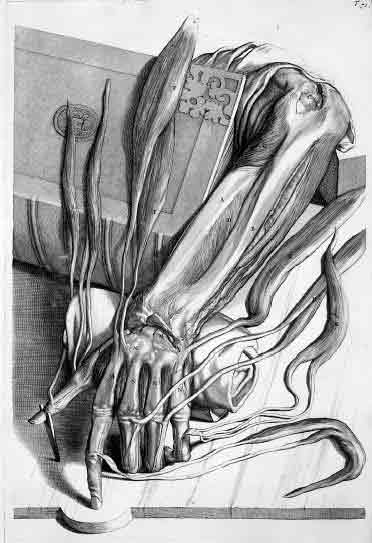

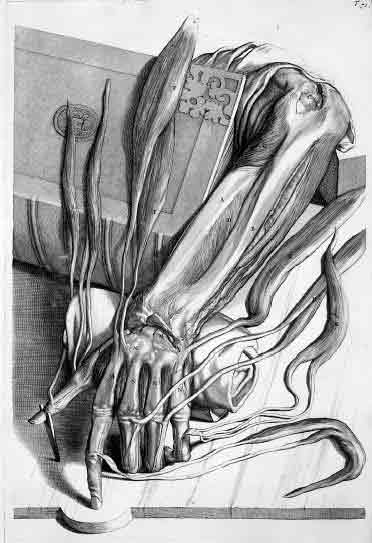

Excerpts from Essential Anatomy Dissector by John. T Hansen. Copyright 1998 by Williams & Wilkins. Reprinted by permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Excerpt from A Green Crabs Shell from Atlantis by Mark Doty. Copyright 1995 by Mark Doty. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Excerpt from The Burial at Thebes: A Version of Sophocles Antigone by Seamus Heaney. Copyright 2004 by Seamus Heaney. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC and Faber and Faber Ltd. Excerpts from Death, Dissection and the Destitue by Ruth Richardson. Copyright 1987, 2000 by Ruth Richardson. By permission of University of Chicago Press. Excerpts from Post-Traumatic Stress Among Medical Students in the Anatomy Dissection Laboratory by Peter Finkelstein and Lawrence H. Mathers, Clinical Anatomy, 3: 21926 (1990). By permission of Clinical Anatomy. Excerpt from The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, translated by Nevill Coghill. Copyright Nevill Coghill 1951. Copyright the Estate of Nevill Coghill, 1958, 1960, 1975, 1977. Reprinted by permission of Penguin Books Ltd. Excerpt from Five Poems for Grandmothers: Part V from Selected Poems II: Poems Selected and New 19761986 by Margaret Atwood. Copyright 1987 Margaret Atwood. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. Late Fragment from A New Path to the Waterfall by Raymond Carver. Copyright 1989 by Raymond Carver. Reprinted by permission of International Creative Management, Inc. All images are from De Humani Corporis Fabrica by Andreas Vesalius, except the image on page 30 which is from Anatomia Humani Corporis, Centum & Quinque Tabuli by Govard Bidloo. By permission of Brown University Library.

ISBN: 978-1-1012-0233-3

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

For Deborah,

and for Eve

Contents

Dispel from your mind the thought that

an understanding of the human body in every aspect

of its structure can be given in words

L EONARDO DA V INCI

preface

Mystery

I have said that the soul is not

more than the body

And I have said that the body is not

more than the soul

W ALT W HITMAN , L EAVES OF G RASS

F lat-calm summer evenings on the northern Michigan lake of my childhood, Id tug on my swimsuit and wade out in the clear green water to float. No matter how far out I walked, I could hear my familys voices on our dock, my fathers deep-toned stories, my grandmothers broad, cackling laugh. But when Id lie back in the water, arms and legs spread out like a snow angel, the lake would cover my ears with a storm of silence. Id lie there and breathe, loving the way my body would rise and fall. I thought that I was the only moving thing in the stillness of the deep waters. Id exhale slowly and let my body sinkmy feet and legs first, then hips and chest, and just when all of me was submerged except my mouth and nose, Id breathe in again and float back to the surface, as if gravity were a law you could choose to disobey.

What was this breath force within me? I never knew. Sometimes I would feel the water seep up to the corners of my nose and mouth; Id keep exhaling and let my body sink to the bottom. There Id lie, staring up at the surface, with its mercurial shine. In those moments, with my world tinged in foggy hues of green, I felt like the lone inhabitant of a sacred space: my whole young self held close and rocked by the water. But before long, out of air, Id have to thrust myself back to the surface to float some more. When I got cold or tired, Id walk back in, toward the voices and the laughter, wondering what domain my small breath had over water, how both air and lack of it could make me rise.

I still think of that quiet, of that sense of something powerful and unseen in me that I both could and couldnt control, of the understanding that sometimes lifes truths seem to contradict each other. Now I am a student of medicine, a field with its own great paradoxes. The first of these I encountered in my anatomy class, and it is still one of the most powerful: that you begin to learn to heal the living by dismantling the dead.

The dead body harbors the great mysteries of creation and humanity: the hidden beauty and intricacy of function, the insistence of individuality, the inevitability of decline, the incontrovertibility of death set up against the ill-defined boundaries of life. Opening the body begins to unveil these mysteries. Centuries upon centuries of doctors have done so in search of wonder and knowledge.

The moment I raise a scalpel to a body is a rite of initiation. With my first cut, I have begun a personal transformation that differentiates me from my friends and family. This book is about that transformation. It is about performing previously unthinkable actions in order to discover wondrous and previously unimaginable realms. It is about joining a history of anatomy that includes grave robbers and executioners, murderers and mutants, courageous blasphemers and the bodies of saints. This book is about dissecting a dead body in the hopes of one day making living bodies more whole.

I am now in my final year of medical school, mere monthsS away from being called Doctor. Before I began my medical training, I was at various times a poet, a university writing instructor, a high-school English teacher to a group of troubled kids. I am older than all but a handful of my classmates and share a comparatively adult life in a little bungalow with my partner of more than seven years and our sweet old dog. I have family members who are sick, perhaps dying. I bring each of these perspectives to medicine, and indeed to the dissection table; they have informed my experience of becoming a doctor, and they have shaped what I have written here. But in the end this book comes from my interactions with the bodies of strangers, both dead and living, and the privileged view that I was given into their innermost workings and failings.