ALSO BY CHRISTINE MONTROSS

Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality from the Human Anatomy Lab

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA Canada UK Ireland Australia New Zealand India South Africa China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

Copyright Christine Montross, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint excerpts from the following copyrighted works:

Crazy words and music by Thomas Cee Lo Callaway, Brian Burton, Gianfranco Reverberi, and Gian Piero Reverberi. 2006 Warner/Chappell Music Publishing Ltd., Chrysalis Music Ltd., Universal Music Publishing Group, and BMG Ricordi Music Publishing SpA. All rights for Warner/Chappell Music Publishing Ltd. in the U.S. and Canada administered by Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp. Chrysalis Music (ASCAP) administered by Chrysalis Music Group Inc., a BMG Chrysalis Company. (Crazy contains elements of Last Man Standing by Gianfranco Reverberi and Gian Piero Reverberi, BMG Ricordi Music Publishing SpA.) All rights reserved.

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening from The Poetry of Robert Frost, edited by Edward Connery Lathem. Copyright 1923, 1969 by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright 1951 by Robert Frost. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

In a Dark Time copyright 1960 by Beatrice Roethke, Administratrix of the Estate of Theodore Roethke. From Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke. Used by permission of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc. Any third-party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited. Interested parties must apply to directly to Random House, Inc. for permission.

Human Personality from Selected Essays by Simone Weil, translated by Richard Rees. Copyright Richard Rees, 1969. Reprinted by permission of Peters Fraser & Dunlop on behalf of the Estate of Richard Rees. Published in French as La personne et le sacr from Ecrits de Londres et dernires lettres by Simone Weil. Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1957. By permission of Editions Gallimard.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

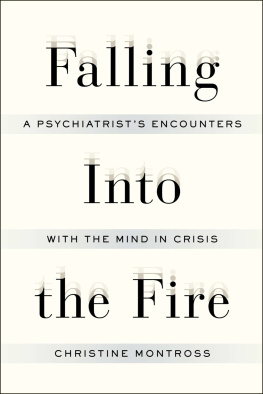

Montross, Christine.

Falling into the fire : a psychiatrists encounters with the mind in crisis / Christine Montross.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-101-61778-6

I. Title. [DNLM: 1. Mental DisorderspsychologyPersonal Narratives. 2. Mental DisorderstherapyPersonal Narratives. 3. Attitude of Health PersonnelPersonal Narratives. 4. BehaviorPersonal Narratives. 5. Mentally Ill PersonspsychologyPersonal Narratives. 6. Physician-Patient RelationsPersonal Narratives. WM 140]

RC438.6.M665

616.890092dc23

[B]

2013007699

( AUTHORS NOTE )

The names of all patients and certain details of their stories have been changed in order to preserve confidentiality. For the same reason, the names of some of my colleagues have also been changed.

For Deborah and my children, who multiply my lifes joy

And for my patients, who help me to never take that joy for granted

( CONTENTS )

To acknowledge the reality of affliction means saying to oneself:... There is nothing that I might not lose. It could happen at any moment that what I am might be abolished and be replaced by anything whatsoever of the filthiest and most contemptible sort. To be aware of this in the depths of ones soul is to experience non-being. It is the state of extreme and total humiliation which is also the condition for passing over into truth.

Simone Weil

They called me mad, and I called them mad, and damn them, they outvoted me.

The Restoration playwright Nathaniel Lee, regarding his committal to Bethlem Royal Hospital

( PROLOGUE )

Bedlam

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased?

Shakespeare, Macbeth

I n early January, Charles Harold Wrigley, a twenty-two-year-old gas engineer, was brought by his family to the psychiatric hospital. The patient is extremely depressed, the evaluating physician wrote. He sat with his hand on his forehead as if in pain during my interview. He says everything he does is wrong and that he is very miserable. A second doctors note adds, I am informed... that the patient has suicidal tendencies and since he has been [at] this hospital has attempted to strangle himself. Notes like these are familiar to me. As a psychiatrist, I have seen countless patients in emergency rooms, inpatient units, and outpatient offices whom I might have described in nearly identical terms. This patients symptoms are not striking; however, the familiarity of the description is, considering that Charles Harold Wrigley was evaluated and treated at Englands Bethlem Royal Hospital in 1890.

Before I became a doctor, I had more faith in medicine. I thought that medical school and residency would teach me the bodys intricacies, its capacities to heal and to falter, and all of our various methods of intervening. Once I mastered these, I thought, I would really know something. That has turned out to be partially true. I know many more things about the bodyits wonders and its failingsthan I could ever have imagined. But as a doctor, I have emerged from my training with a shaken faith. If I hold my trust in medicine up to the light, I see that it is full of cracks and seams. In some places it is luminous. In others it is opaque. And yet I practice.

At times this doubt is disillusioning. More often, however, Ive come to view the questions that arise as a vital component of the work of medicine. My faith in medical knowledge has shifted into a faith that the effortthe practiceof medicine is worthwhile. I cannot always say with certainty whether the course of treatment I prescribe will heal; I cannot always locate with precision the source of my patients symptoms and suffering. Still, I believe that tryingto heal my patients and to dwell amid the many questions that their illnesses generateis a worthwhile pursuit.

I have found that one of the gifts of medicine is that it allows those who practice it to participate in the purest and most vulnerable moments of human life. As doctors we share in the utter joy of birth, the irrepressible relief of a normal scan or a benign biopsy. We deliver earth-shattering diagnoses. We accompany people to their deaths. In these moments there is not much room for the protective or insulating layers that peopleall of usput upon ourselves in our daily lives. Joy is joy, and grief is grief, and fear is fear; and in the context of medicine, those emotions are often at their most primitive and raw. As an inpatient psychiatrist, I treat people who are in moments of profound crisis. The majority of them are hospitalized because they might not be safe otherwise. I do not lose sight of the fact that my patients come to me in these precarious states.

I am a few years into my psychiatric practice. Relatively speaking, I am new to the job. Every day that I go to work on the inpatient psychiatry wards, I encounter people who are despondent, or terrified, or raving mad. I see people whose lives have been ruined by addiction. I hear unfathomable things that people have done to others, from familial betrayals to brutal attacks. I talk with people who, more than they have ever wanted anything, want to die. It is not a dull job.