Living Through the End of Nature

Living Through the End of Nature

The Future of American Environmentalism

Paul Wapner

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2010 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142.

This book was set in Sabon by the MIT Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wapner, Paul Kevin.

Living through the end of nature : the future of American environmentalism / Paul Wapner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-01415-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-262-26570-6 (retail e-book)

1. EnvironmentalismUnited States. 2. Conservation of natural resourcesUnited States. I. Title.

GE197.W37 2010

333.720973dc22

2009036083

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Diane, Eliza, and Zeke

for everything

Acknowledgments

One of the main points of Living Through the End of Nature is that life is interdependent. The earth is a swirling mixture of plant, animal, and mineral with no entity able to exist without others. In writing this book, I have been fortunate to experience this in a concrete way. Not only has the sun shone down on me every day and the earth provided abundant sustenance; I have also lived and worked among concerned colleagues, inspiring students, dear friends, and a loving family. Acknowledging these connections is one of the deepest joys in completing the manuscript.

First, I would like to thank my colleagues in the School of International Service at American University. Dean Louis Goodman has long provided support and enthusiasm for my work, and through many conversations, helped clarify the arguments of the book. Simon Nicholson and Judy Shapiro each assisted me at critical junctures, and supplied sustained intellectual engagement. Leah Baker, Eve Bratman, Ritodhi Chakraborty, Benjamin Goldstein, Brendan Havenar-Daughton, Rongkun Liu, Antone Neugass, Marysia Szymkowiak, Rachna Toshniwal, Bonnie Washick, and Deidre Zoll offered valuable research assistance, for which I am particularly grateful. I am especially appreciative of my students. American University tends to attract people committed to making the world a better place. Whatever insights this book may have, many of them emerged through conversation and engagement with American University students.

Outside of American University, I have flourished in the company of scholars and others who have been caring about the earth in the most meaningful ways. Much of the books argument crystallized while backpacking with Leslie Thiele and his many suggestions have improved the manuscript. Les has always provided intellectual companionship, wise counsel and lots of laughs. The book has also benefited from long country walks and conversations with Terry Post, conference discussions with Michael Maniates and Thomas Princen, and late night chats with Dirksen Bauman about the nature of nature. I presented aspects of the argument in seminars at Bowdoin College, University of Maryland, Rutgers University, the Lama Foundation, and the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. I learned a lot from and am thankful for these opportunities. I am particularly grateful to Peter Dauvergne. Peter holds the record for reading the manuscript multiple times, encouraging me in moments of doubt, and generously offering incisive suggestions for improving the books overall quality. Clay Morgan, at the MIT Press, read through the entire text with a keen editors eye and expressed enthusiasm for the project in ways that have meant a lot to me.

From a different corner of my life, dear friends provided meaningful support as we lived together through the years in which this book was written. I would especially like to thank Dirksen Bauman, Joanna Bottaro, Sheila and Peter Blake, Kristin Dahl, Hilal Elver, Richard Falk, Sue Katz-Miller, Paul Miller, Robert Nelson, Mitchell Ratner, and Nicole Salimbene for the many conversations about nature as well as their friendship.

As always, my parents, Elinor and Morton, and siblings, Howard and Susan, have given me unwavering support and endless love. I thank them from the bottom of my heart.

This book is dedicated to my family. Eliza, Zeke, and Diane are the stars that shine daily for me and make life more than worth living. I suppose it is inappropriate to thank them for being who they are, but I sure appreciate them constituting my life.

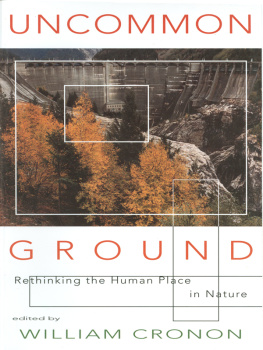

Note on Photographs and Sources

Nicole Salimbene, a visual artist living in Tacoma Park, Maryland, generously provided the photographs that appear before each chapter. Nicole works in a variety of media to explore themes of intimacy, political voice, and devotion. The photographs in the following pages are part of a study that examines the constructed quality of nature, and the place of memory and reverence in our engagement with the natural world. I am extremely grateful to Nicole for allowing her work to be shown in the context of the book and for inspiring me to think visually about the end of nature. Zeke Wapner, my son, provided the cover photograph. The image captures his interprtation of what it means to live amidst profound change in both the human and natural worlds. I very much appreciate Zekes keen photographic eye and his engagement with this book. I have written the text in a way that I hope speaks to everyone. The challenges of living through the end of nature are not the sole domain of professional environmentalists or scholars of environmental studies, but demand engagement from all of us. With this in mind, I have tried to avoid academic jargon and to minimize the number of references. Citations appearing in the text refer only to essential works and those that most readers may be inclined to consult. The limited number of references should not hide the fact that I am indebted to countless scholars, journalists, and others for their insights into contemporary environmental affairs. This book is a product of many peopleeven if many of their names escape its pages.

Reweaving the Path, Lama, New Mexico

1 Introduction

If you stand right fronting and face to face to a fact, you will see the sun glimmer on both its surfaces, as if it were a cimeter, and feel its sweet edge dividing you through the heart and marrow.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden

A number of years ago I was talking to a friend about a philosophical problem. I emphasized how the issue had perplexed thinkers throughout the ages, and how the accumulation of thought over the centuries had only rendered the problem that much thornier. I urged her to appreciate the depth of the dilemma and take up the challenge of resolving it. Not ignoring my sense of purpose, she nevertheless turned to me at one point and said, Paul, this is where you and I part company. At this stage in the discussion you look at the unresolvable nature of the problem and say, Oh no! I look at it and say, Oh well.

Many of us worry about things that others consider irrelevantboth philosophical and empirical. Some of us get wrapped up in abstract questions that others find abstruse, and many of us are disturbed by social dilemmas to which our friends and colleagues are indifferent. The combination describes many an environmentalist. Environmentalists worry about the well-being of the earth. We care about fresh air, clean water, healthy soils, and the planets capacity to support human life and ecological abundance. While these are genuine concerns, there is something nonetheless abstract about them. Few of us live on the front lines of severe environmental harm, and our concerns for the earth as a whole are fundamentally theoretical insofar as no one can see and experience the planet in its entirety. Yes, we have viewed those famous photographs from space, and have seen pictures of the Katrinas, Chernobyls, and clear-cuts of the world. But to capture these in thought and develop a sense of care about them requires us to rise above our immediate experience. When we do so, sadly not everyone joins us. Distressing about the earth is often a lonely exercise in abstract worry. Yet worry we do. We see lots of things happening that dont sit right with us.